I adore baseball! February of every year is wonderful for two specific reasons: Ash Wednesday occurs, the harbinger of Lent and Easter, and pitchers and catchers of Major League Baseball report first to Arizona and Florida, followed by the rest of the position players, for the start of Spring Training, that grand sun-splashed event that precedes the beginning of the regular season, around April Fool’s Day. Even this year, 2021, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues its rages, however now somewhat diminished, a nearly complete season will, barring viral flare-ups, be played, albeit constituting a somewhat shortened 154 game schedule. Every team in baseball now possesses a 0-0 record and hopes to win all the way to the World Series. And even though some of us fans know all too well that our favorite team—the Texas Rangers in my case—has little real chance to get to that series, we still hope against hope that a baseball miracle will occur, that all those unknown pitchers will blossom into 20-game winners, that those struggling hitters will finally discover their strokes, and that that leaky defense will at last find its way to a host of Gold Gloves. February is far from Chaucer’s “Cruelest month,” but it is too often true for my team that April turns out cruel year after year.

I adore baseball! February of every year is wonderful for two specific reasons: Ash Wednesday occurs, the harbinger of Lent and Easter, and pitchers and catchers of Major League Baseball report first to Arizona and Florida, followed by the rest of the position players, for the start of Spring Training, that grand sun-splashed event that precedes the beginning of the regular season, around April Fool’s Day. Even this year, 2021, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues its rages, however now somewhat diminished, a nearly complete season will, barring viral flare-ups, be played, albeit constituting a somewhat shortened 154 game schedule. Every team in baseball now possesses a 0-0 record and hopes to win all the way to the World Series. And even though some of us fans know all too well that our favorite team—the Texas Rangers in my case—has little real chance to get to that series, we still hope against hope that a baseball miracle will occur, that all those unknown pitchers will blossom into 20-game winners, that those struggling hitters will finally discover their strokes, and that that leaky defense will at last find its way to a host of Gold Gloves. February is far from Chaucer’s “Cruelest month,” but it is too often true for my team that April turns out cruel year after year.

As a long-time fan of nearly 70 years, I know all too well the constant cries of the demise of my favorite baseball. It is certainly true that it should no longer be called “America’s pastime,” since the bone-jarring football has over the past two decades probably taken that name. Besides, it is said that baseball is “too slow and boring.” This is usually said by those who have little inside knowledge of the game, and who have not played the game much. Baseball is not slow! It is intricate, filled with finesse, riddled with strategy and positioning, a sport not merely of inches but of millimeters, the tiniest fractions of the movements of the ball deciding winning and losing on a daily basis. And baseball is about failing a significant amount of the time. The very finest hitters fail 7 out of ten times; the very best pitchers win more than they lose and strike out more hitters than they walk or to whom they surrender hits, but the margins of their victories are often razor-thin, determined as much by those who are in the field behind them as the accuracy with which they hurl the sphere toward the plate.

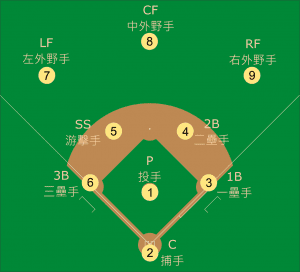

And like all team sports, it is based on a team concept where every member plays a huge role in winning and losing. This obvious fact is true about the other sports as well, but no other sport demands individual prowess, coupled with complete team dependence, as baseball. Basketball is a sport thoroughly dominated by its superstars, those individuals who pour in 30 points a night, who grab 10 rebounds, who dish out 10 assists. The final five members of the 15-person basketball team, who “ride the pine” game after game, may find a larger role in the team’s practices, but in the games, they are reduced to well-paid observers. Football’s huge rosters are necessitated by the constant injuries that the sport dishes out. The 22 starters on offense and defense are backed up by over 30 other players, several of whom rarely step foot on the game-time field, and like their basketball counterparts, find their field time only in practice. Baseball’s starting 9 are backed this year by 17 players on the bench, among whom are found some 11-12 pitchers. In reality, the so-called utility players, those who do not start in the field, areonly some 4-5, who are called on to play multiple positions when injuries or the need for rest occur. And due to the long season, injuries will happen and rest will be needed. Hence, those 4-5 non-starters will surely be needed regularly. I suggest that the individual player on a baseball team is forever under the bright spotlight of all who evaluate performance, and must play both an individual role at his position, a role that adds or detracts to the success of the team quite directly. A shaky shortstop leads to a less-than- confident second-baseman and a decidedly uncomfortable pitcher. Those connections are obvious, unmissable, devastatingly clear to any who watch the game. A basketball forward may be out of position in a called play, but only the insider will recognize that fact. An offensive lineman may have missed a blocking assignment, but only instant replay and an astute commentator will make that plain. When the shortstop flubs a routine grounder, everybody knows immediately and groans accordingly. And because in baseball all must play both offense and defense (save pitchers in the American League and its designated hitter), each player can be booed again and again for that flubbed grounder or dropped fly ball, each time they approach the batter’s box.

Baseball is a fabulously democratic game; it is available to all, both to play and to watch. When I entered high school, I was 4’ 11” tall and weighed 96 pounds in my shoes. Football and basketball were effectively closed to me, but I could still play baseball. I was a decidedly poor catcher, with a middling arm, a decent ability to block errant fastballs, and a genuine delight in calling a game. I did not play much, I assure you, and not at all on the high school team. Only in the summers, in a broiling hot Phoenix, was I able to don “the tools of ignorance,” i.e. that catcher’s sweaty gear, and enjoy the game in several youth leagues. I was never going to play the game in any other way, though I spent a few weeks as a freshman on my Grinnell College team. When I realized that if I played baseball, however poorly, I would need to drop out of the college choir. I was clever enough to realize that I had a rather better chance to be singing as an adult than playing baseball. It was the obvious choice; I stayed in choir.

Still, those few days as a player were determinative for my love of the game. I know a tiny bit of what it takes to play the game and to play it well. And I also know just how amazingly right the game is. 90’ between the bases is precisely correct to make the throw from the shortstop to first base possible to make an out even with the very fastest of runners. I know that the 60’ 6” from the pitcher’s mound to the front of home plate is just right to allow the pitcher to trick the batter often, but also just right to allow the better batters to assess and to hit that nasty curve ball or that sneaky slider or change-up. And the outfields, left, center, and right, are spacious enough, yet contained enough, to allow the better fielders to make the great catch, to use their powerful arms to throw runners out at second, third, or home, if not every time, at least often enough to ratchet up the excitement each time the fielder launches a throw from deep in the outfield.

The better pitchers will trick the better hitters the large majority of the time, while the better hitters will get their hits no matter who the pitcher may be. The thrill of baseball is the anticipation of what can happen in the face of the long reality that it may not, probably will not, but on delightful occasions actually does. In that regard, baseball is in fact rather like belief in God. Such belief is based on a hopeful expectation that the world will improve, that love will triumph, that justice will prevail. None of those things happens each and every time, but they do happen. Home runs are hit to win the game; fabulous catches in the field are made to save the game; strong-armed pitchers do strike out the best hitters, though at times that same hitter achieves the game-winning hit off that same pitcher. I have watched thousand of baseball games, and all of these things have happened. But they were never a certainty, just a possibility. In that hope lies the thrill of baseball. And in that hope lies a belief in the presence of God.

I am certain that God loves baseball, and that if she or he played the game, she/he would find in it the same anticipated hopeful joy and pleasure that I have found. I like to think that God would be a catcher, calling the game, trying to direct the proper positioning of the fielders, urging the pitcher to stay with his best pitch of the day, whether it be fastball or curve, but not finally able to control every action of the team. At one time or another, every team member will fail, but I like to think of the catcher-God at the end of a loss, gathering the team around, and saying, “Put the loss behind you all! Tomorrow is another day!” And in God’s sight, her eyes streaming with sweat behind that cage-like mask, it is indeed another day tomorrow.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)