The stories about Samuel, Saul, and David, that comprise among the very greatest of tales from the ancient world, are so rich and so detailed that it is frankly impossible to encompass the whole of them in only a few weeks of preaching or teaching. Yet, each section of the vast whole reveals something new and fresh about the characters that drives the plot toward its generally tragic end. 1 Samuel 31 records the sad death by suicide of Saul on Mt. Gilboa, though 2 Sam.1 gives us another account of Saul’s demise. A careful assessment of this wandering Amalekite’s tale of his killing of the dying king rather easily reveals that the thief is in fact lying, a grotesque untruth that results in his own brutal murder by one of David’s henchmen. Of course, Saul’s end makes David’s new beginning as king at last possible. However, there are certain uncomfortable facts about David and his activities and relationships, both with Saul and with Saul’s son, Jonathan, that must be dealt with effectively if David is to have relatively smooth sailing to the throne of Israel. In the grand poem in 2 Sam.1, David is revealed to us as a superior artist and a clever politician as he weaves into the poem what is needed for him to be seen as the next and only possible king of the land.

The stories about Samuel, Saul, and David, that comprise among the very greatest of tales from the ancient world, are so rich and so detailed that it is frankly impossible to encompass the whole of them in only a few weeks of preaching or teaching. Yet, each section of the vast whole reveals something new and fresh about the characters that drives the plot toward its generally tragic end. 1 Samuel 31 records the sad death by suicide of Saul on Mt. Gilboa, though 2 Sam.1 gives us another account of Saul’s demise. A careful assessment of this wandering Amalekite’s tale of his killing of the dying king rather easily reveals that the thief is in fact lying, a grotesque untruth that results in his own brutal murder by one of David’s henchmen. Of course, Saul’s end makes David’s new beginning as king at last possible. However, there are certain uncomfortable facts about David and his activities and relationships, both with Saul and with Saul’s son, Jonathan, that must be dealt with effectively if David is to have relatively smooth sailing to the throne of Israel. In the grand poem in 2 Sam.1, David is revealed to us as a superior artist and a clever politician as he weaves into the poem what is needed for him to be seen as the next and only possible king of the land.

David’s difficulties may be summarized as follows: 1) While Saul and his army has been soundly and brutally defeated on Gilboa, David has been living for nearly 18 months in a Philistine city, Ziklag, a city given to him by his apparent Philistine patron, Achish of Gath. It will be important for David to say clearly that he is not enamored of the Philistines, is certainly not their ally, and was not merely resting comfortably in Ziklag without trying to join Saul in the fight. 1 Sam.29 records David’s attempt to fight alongside the Philistines (!), but is rejected because the Philistines simply do not trust him to kill Israelites, his own people. And he is in Ziklag because he has been driven there by a mad and enraged Saul, who wants nothing less than David’s death. 2) David at least twice has had a chance to kill King Saul, but has relented each time. Saul, on the other hand has tried to murder David more than once, but has been thwarted each time. It will be important for David to say plainly that he and Saul, despite outward appearances, were never really enemies, since if David is to rule the whole of the land, he must convince Saul’s associates that they may trust his leadership. 3) David’s relationship to Jonathan must have been the subject of speculation. Saul accused his son of “uncovering the nakedness of your mother,” a nasty phrase, fraught with sexual innuendo. On several occasions, Jonathan quite literally threw himself at David, no less than at their very first meeting when Jonathan strips off most of his clothing and gives it all to a David with whom he is clearly smitten. Such rumors must be dealt with. These problems, along with several others, must be handled with delicacy and tact, and David rises well to the occasion.

Scholars have long argued that it is extremely difficult, if not finally impossible, to connect David with the composition of any of the 150 canonical psalms to be found in our biblical Psalter. The superscriptions to the psalms, added many centuries after the poems themselves, that say, in the usual translation, “a psalm of David,” may just as easily be read “a psalm to David,” suggesting the fact that in later days in Israel David became the patron saint of music and poetry. However, if any poetry might be considered to be from David’s own heart and harp, this poem in 2 Sam.1 could be a likely candidate. No one can conclusively prove the connection, but if I am right to suggest that the man David had certain political needs that a fine poem might begin to satisfy, then this piece could reasonably be connected to David as author. I will make that assumption in what follows.

The poem begins with a grand gesture:

“The splendor, O Israel, has been slain on your heights;

How the mighty warriors have fallen!

David chooses the first word of the poem well; the NRSV’s translation “glory” does not do full justice to the meaning. The word may mean “splendor, beauty, or honor,” each nuance adding to the greatness of the subjects of the song, now slain on the high place of Gilboa. Immediately, David follows this encomium to the dead king by turning to the Philistines, David’s physical mentors, and demanding that they not be allowed celebrate the death of Israel’s king, not in Gath’s streets, nor in the byways of Ashkelon, where no “daughters of the uncircumcised” should be able to gloat. In this way, David separates himself from his Philistine hosts forever, casting them as little better than heathen, and making it plain that if he ever did consort with them, he has now left them for all time.

The poet then prays that no dew or rain should ever again fall on the hill of Gilboa, its perpetual drought a living sign of the dry and sear place that it must become as witness to the monstrous deaths upon its soil. David then turns more specifically to the human objects of the poem, Saul and Jonathan.

“Jonathan’s bow did not retreat,

the sword of Saul never turned away empty.

Saul and Jonathan, beloved and dear,

in their life and their death they were not parted.”

Here David stretches the truth to the breaking point in order to hymn the inseparable nature of the relationship between the royal father and son. Of course, many will have known all too well the tales of Saul’s angry denunciation and rejection of Jonathan, precisely because of the son’s choice of David over his furious father. Yet it is important that now that the two are dead that such unpleasantness be forgotten, and that unity rule the day.

“Daughters of Israel, weep over Saul,

who clothed you in scarlet luxury,

who studded your garments with golden jewelry!”

Saul was always concerned to share his victories with his people, scattering all manner of battle goods among women and men, adorning them in beauty, acting as a great warrior king always acts. Then, as the poem moves toward its end, David addresses his relationship to Jonathan.

“Jonathan, on your heights slain!

I grieve for you, my brother Jonathan,

very dear you were to me.

More wonderful your love for me

than the love of women.”

David’s treatment of this close relationship is a masterpiece of tact. Jonathan, heir to Saul’s throne, is in fact David’s brother-in-law, so to name him brother is only to state the truth. But then David records intimate feelings in the relationship, but we note that though Jonathan was only “dear” to David, a fairly generic claim. In the other hand, however, David says that Jonathan’s “love for me was more wonderful than the love of women.” It is noteworthy, as we read through the passages that comment on Jonathan and David’s interactions that no where are we told that “David loved Jonathan,” while several times it is said that Jonathan fairly doted on David. In addition, the phrase concerning love beyond the love a woman is designed to describe the deepest affections between two warriors; a bond in a culture of warriors could readily be stronger, though different, than a bond between man and woman. Nothing of any sexual nature should be drawn from the poem, though several commentators have tried to do so.

The poem ends with a grand flourish, with a repetition of “how have the mighty warriors fallen,” followed by the piercing image of battle gear lost, or the “weapons of war perished” (NRSV). I suggest that David has accomplished in the poem exactly what he set out to do. He has separated himself from the Philistines; he has praised Saul’s and Jonathan’s united battle prowess and deeply lamented their loss; he has grieved over Jonathan, saying that with his death, that manly love he felt for David has ended forever. It is a deeply felt lament, and a masterpiece of political magic. With this poem David is thoroughly revealed to us a most skilled and complex man, a portrait that we will see repeated and enhanced as his rise and fall are witnessed in the succeeding chapters. We are to see David in ourselves in these magnificent portraits. Like him, we too are a mixture of skill, faith, self-serving desire, and political cleverness. Like him, we are both those who attempt to follow our God and who too often follow ourselves. That notion remains one of the Bible’s greatest gifts to us.

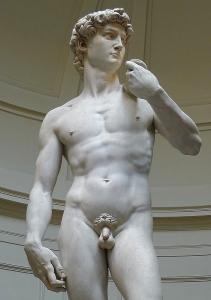

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)