I have taken several short-term mission trips over the years, trips in which I have been involved mainly in building something or the other. On two occasions in Guatemala I found myself building cinder block houses. Well, to be more accurate I was the one mixing the mortar for the “maestro” who was the one doing the actual work of building. Or I was the one trying to dig the trenches into the packed earth into which some skilled person would lay the rebar to form the beginning of a home. No one would allow this Hebrew Bible PhD within ten cubits of the actual deed of building! Unlike Stanley Hauerwas, I have never built anything in my entire life. In fact, on one of my Guatemala trips, I was tasked with moving a room full of sand out of a spot in order that the builder could get into the place and work. (I later learned from another short-term missioner that she had moved that very pile of sand back into that very same room to get it out of the rain! Such are the vagaries of mission work!)

I have taken several short-term mission trips over the years, trips in which I have been involved mainly in building something or the other. On two occasions in Guatemala I found myself building cinder block houses. Well, to be more accurate I was the one mixing the mortar for the “maestro” who was the one doing the actual work of building. Or I was the one trying to dig the trenches into the packed earth into which some skilled person would lay the rebar to form the beginning of a home. No one would allow this Hebrew Bible PhD within ten cubits of the actual deed of building! Unlike Stanley Hauerwas, I have never built anything in my entire life. In fact, on one of my Guatemala trips, I was tasked with moving a room full of sand out of a spot in order that the builder could get into the place and work. (I later learned from another short-term missioner that she had moved that very pile of sand back into that very same room to get it out of the rain! Such are the vagaries of mission work!)

I fully appreciate the heated arguments that have been generated by these sorts of trips. Is it finally of any lasting value that some rich and comfortable American do- gooder spends a week of so away from his air conditioned car and home and sweats a bit among persons who live in genuine poverty only a few hours’ plane ride from his comfort? And does that trip offer insight or change to him who goes and/or joy or change for those whom he visits? I think the answers to those questions are hardly simple ones, and this brief essay will not attempt to wade in those murky waters. What I do know is this: my trips to Guatemala and El Salvador have imprinted on my mind scenes that will never leave me, portraits of people, both smiling and weeping that will be with me forever. And more than that: I know at least one or two families who now live in a solid if simple house, protected from the cold and the heat and the wet, at least partly due to my menial efforts. By any measure, that is not nothing; equally, by any measure it is not the saving event of the world.

I suppose that my very first trip like these to Juarez, Mexico was the one that affected me the most. I went to Juarez in 1999, flying to El Paso, TX, and then busing over the border into a world so different from my own that it was very difficult to take it all in. The city of Juarez itself is not unlike many third-world places, filled with simple shops, tourist bars and curio stands, and some restaurants. Most of that was generally familiar from other trips into Central America. I should add that nearly 20 years ago, Juarez was not the very dangerous place it has become in the years since. For a time only a few years ago, it was named the murder capital of the world due to the drug-fueled cartel wars that raged in the streets of the city. Though it has improved recently, it is not a place recommended for visits, though it is the closest Mexican town to the bustling community of El Paso.

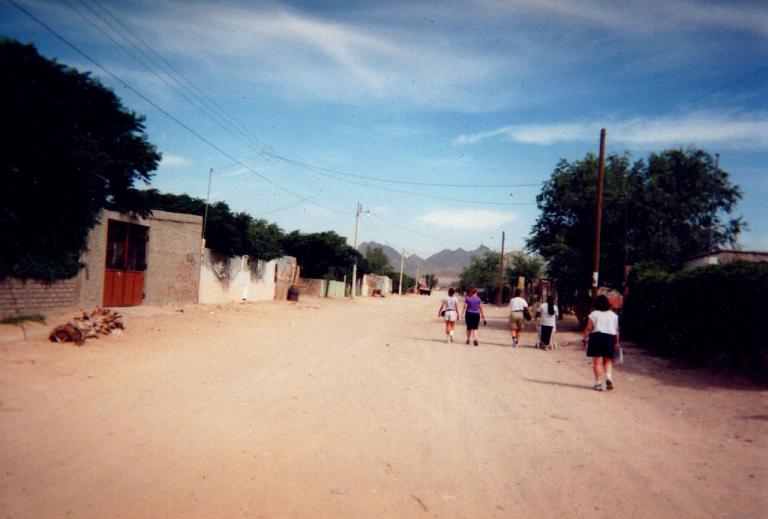

We did not come to Juarez to work in the city proper. We went rather to the barrio outside the city, a place with sand-filled streets, one water pipe per street for the needs of all who lived on that street, no traffic lights, and very few stores of any kind. All the buildings were made of cinder block and we had come to add to that stock. Earlier groups had come to begin to build a small clinic, since medical services were in short supply in this community for its thousands of poor residents. The clinic was far enough along that only more skilled workers would be needed to finish it; we were hardly the skilled workers they needed for that project. We were going to build a simple home.

The first night we were there, sleeping in a cinder block dormitory, I noted that one could easily see the lights of El Paso from our quarters. There, in plain sight, lay a first-world city, filled with cars and large homes with police and fire protections, access to an international airport, along with all of life’s supposed necessities. From where we lay, we saw few lights, saw little evidence of police presence or fire fighters, heard the sound of no jets departing and landing from places around the world. We heard a radio playing mariachi music, heard the tinkle of bottles as the locals frequented the only bar in the area. Mostly, we heard nothing but the sound of the wind, moving the dunes of sand around in the streets, streets that shifted with the blowing sand.

Both my wife and our daughter were with me on this trip. Sarah, the daughter, was, I think, a junior in college, and my wife was pastor of a church in Duncanville, TX. I was in my 20th year on the faculty of my seminary in Dallas. I was assigned two jobs: to stack the cinder blocks within easy reach of those who were building “our” house and to mix an ever-needed volcano (“vulcan” in Spanish) of mortar (the same word in Spanish, but with the accent on the second syllable rather than the first). I can still hear the crisp call of the maestro, “mas mortar!” as I type this. For each of the five days we were there, I lifted cinder blocks and mixed mortar. Our meals were all lovingly supplied by the locals, meals of water, the occasional coke, and combinations of tortillas and things to put in them.

On one day, a local woman invited us to her home and proceeded to give us each a piece of needle-pointed lace that she specialized in. It was a fabulous gift for her and for us. Our daughter played on most days with the local children, those who were unable to attend school. Any school was a lengthy bus ride away, and not all were able to go. A select few had been chosen to go to the High School in El Paso, a Methodist supported place that required a nearly four-hour (!) bus ride each way. Those students spent nearly as much time on the bus as in the classroom. A few of them were able to board the entire week in El Paso, but the majority went back and forth each day. When I think of my easy daily walk to my High School in Phoenix, I marvel at the dedication and hopes of those students.

On one day, a local woman invited us to her home and proceeded to give us each a piece of needle-pointed lace that she specialized in. It was a fabulous gift for her and for us. Our daughter played on most days with the local children, those who were unable to attend school. Any school was a lengthy bus ride away, and not all were able to go. A select few had been chosen to go to the High School in El Paso, a Methodist supported place that required a nearly four-hour (!) bus ride each way. Those students spent nearly as much time on the bus as in the classroom. A few of them were able to board the entire week in El Paso, but the majority went back and forth each day. When I think of my easy daily walk to my High School in Phoenix, I marvel at the dedication and hopes of those students.

Our week ended, and we headed back to our two-car, air-conditioned, restaurant- fueled lives. I have never forgotten those folks in Juarez and their lives so wildly different from my own. But what does it all mean? The phrase often uttered—“there but for the grace of God go I”—is little less than blasphemous, I think. Yet, Jesus’ magnificent parable does spring readily to mind: “As you do it to the least of these, my brothers and sisters, you do it to me.” That parable is decidedly not one of the Last Judgment, as it is too often claimed, but rather the parable of the daily judgment. As I lugged the blocks around in the barrio of Juarez, and the woman offered us her lace, we both did it directly for Jesus. Such acts are the very stuff of the realm of God and by them that realm is revealed just one jot more.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)