As I was closing my 33-year career as a member of the Perkins School of Theology faculty, there was an persistent conversation in many churches and their agencies centered around the topic of leadership. What the contemporary church lacked was leaders, we in the seminary were told, and therefore we were urged to take much more seriously our task in forming genuine leaders for the 21st century church. We responded to this summons by creating a Center for Religious Leadership in 2014, focused on the theology of leadership and practical skills that religious leaders need to do their work with maximum effectiveness.

As I was closing my 33-year career as a member of the Perkins School of Theology faculty, there was an persistent conversation in many churches and their agencies centered around the topic of leadership. What the contemporary church lacked was leaders, we in the seminary were told, and therefore we were urged to take much more seriously our task in forming genuine leaders for the 21st century church. We responded to this summons by creating a Center for Religious Leadership in 2014, focused on the theology of leadership and practical skills that religious leaders need to do their work with maximum effectiveness.

It would be very easy to evaluate this creation of a Center for Leadership, an official program of Southern Methodist University, the home of Perkins, with a board, significant funding, and a qualified head of the center, as another attempt to revive the flagging church. And I imagine it would not be difficult to demonstrate that there surely is a measure of truth in the charge; the church is nothing less than desperate to discover keys that could slow the decline of the institution in our increasingly secular days. Statistics are against us church folk wherever we turn; polls show steep degradation of church numbers and church influence. One of the cries of a drowning church is the cry for real leaders. History proves again and again that where strong leadership is absent, institutions collapse and disappear.

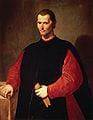

The trick, of course, is to define just what “strong,” or “genuine,” or “legitimate” leadership may in fact be. This question is profoundly complex; new times bring new needs, and new needs require new leaders. That seems a truism, a cliché, that hardly needs proving. However, I would suggest that there is a very basic requirement for an appropriate definition of legitimate leadership, and that is a clear understanding of what church leaders face in the society in which they are called to practice that leadership. Our western culture, at least since the Renaissance, if not before, has presented us with a type of leadership that flies directly in the face of what the church, rooted in its Bible, has been called to practice. At the risk of being overly simplistic, I wish in this essay to explore and contrast two very different styles of leadership, and will then suggest that the church needs to cling fiercely to its biblical model of Moses, while it critiques and ultimately rejects the model offered by the famous political theorist, Niccolo Machiavelli.

In 1513, just four years prior to Martin Luther’s explicit, nailed confrontation with the Roman church, Machiavelli wrote The Prince, perhaps based on the leadership of the infamous Cesare Borgia. This short piece was in effect a job application, intended to display Machiavelli’s credentials as a political advisor. Though the book was not published and widely read until five years after the author’s death in 1527, it was nothing less than a shocking tract that in effect rejected centuries of what leaders were assumed to be. The political ideal of European monarchs had long been seen as moral guides for people to follow all the way to heaven; great power since at least Charlemagne in the 8thand early 9th centuries had always been linked to great goodness. To the contrary, wrote Machiavelli! A good ruler, if he or she was to be seen as good, in the sense of effective, had sometimes to lie, for the simple reason that everyone else lied, even the pope! I hasten to add that Machiavelli was not the conniving monster he has been thought to be, lending his name to the epitome of evil leadership over the past 500 years. What he questioned, and vociferously, was the connection assumed between high morality and worldly success. In short, highly moral leaders do not automatically make effective leaders. Listen to him take on the Christian notion of leadership, based on commonly accepted ideas of Christianity during his time, at the very end of his book: “These principles seem to me to have made men (sic) feeble, and caused them to become an easy prey to evil-minded men (sic), who can control them more securely, seeing that the great body of men (sic), for the sake of gaining Paradise, are more disposed to endure injuries than to avenge them.”

And there you have the foundation of what later was called Realpolitik, that hard- nosed conviction that winners in the games of politics must be willing to fudge the truth, cut some moral corners, and fight back against those who disagree with them. The current occupant of the White House, along with many of his faithful followers, are the epitome of what Machiavelli urged leaders to be; liars when it is helpful to the current cause and fighters against any who dare question the leader’s decisions or programs. Winners perform like that, while losers are weak, pathetic, and beneath the contempt of the strong.

Moses, the lawgiver of Israel, in Exodus 32, had a different idea, and that idea found its most famous expression in the life and death of Jesus of Nazareth. In the ancient story in Exodus, whose written product is certainly 2800 years old, the writer sharply contrasts the Machiavellian Aaron with the resolute Moses when it comes to leadership. The people of Israel, recent escapees from Egypt, are camped at the base of the sacred mountain in the wilderness. In their desperation at the too-long absence of their human leader, Moses, they demand of Aaron, the designated temporary leader of the people, to “make them gods of gold.” Aaron, without a word of demurral, does exactly that. But when all see the finely wrought molten calf, they cry that it was the calf that really brought them out of Egypt, not Moses, and not even YHWH. Aaron attempts to pull back from this obvious religious idolatry and requests a festival to YHWH, but the people, after a brief and typical Israelite worship service, and after dinner on the grounds, “rise up to…?;” what they do is too terrible to be envisioned clearly, but it has to do with some unspeakable forms of sexual play (Ex.32:6).

Moses, the lawgiver of Israel, in Exodus 32, had a different idea, and that idea found its most famous expression in the life and death of Jesus of Nazareth. In the ancient story in Exodus, whose written product is certainly 2800 years old, the writer sharply contrasts the Machiavellian Aaron with the resolute Moses when it comes to leadership. The people of Israel, recent escapees from Egypt, are camped at the base of the sacred mountain in the wilderness. In their desperation at the too-long absence of their human leader, Moses, they demand of Aaron, the designated temporary leader of the people, to “make them gods of gold.” Aaron, without a word of demurral, does exactly that. But when all see the finely wrought molten calf, they cry that it was the calf that really brought them out of Egypt, not Moses, and not even YHWH. Aaron attempts to pull back from this obvious religious idolatry and requests a festival to YHWH, but the people, after a brief and typical Israelite worship service, and after dinner on the grounds, “rise up to…?;” what they do is too terrible to be envisioned clearly, but it has to do with some unspeakable forms of sexual play (Ex.32:6).

Meanwhile Moses and YHWH are chatting on the mountain, when YHWH suddenly stops the conversation and demands that Moses deal with the horrors going on down below. Moses, with clever arguments and honeyed words, assuages YHWH’s fury well enough that God changes the divine mind about immediate Israelite destruction (Ex.32:14). After saving the wretches from YHWH’s rage, Moses heads down the mountain with the tablets of stone, written by God, and on which are inscribed the Ten Commandments. Upon seeing the molten calf, and the orgy going on around it, Moses in his own rage flings the tablets down, shattering them, grabs the calf, burns it up, grounds it down to powder, tosses the powder into some water, and forces the Israelites to drink it. He then demands that Aaron tell him what has happened with the following carefully crafted words: “What did this people do to you that you brought on them a great sin (Ex.32:21)? Aaron is plainly guilty, but Moses gives him a chance to suggest that his

guilt may not be so bad. Aaron, unfortunately, digs himself a deeper hole. “You know the people, my lord, (how obsequious he now is, not even speaking Moses’s name) how they are in evil” ( a literal translation). He seems to mean that the people are thoroughly incorrigible; what else can one expect from such people but evil? “I asked them if they had any gold, they brought me some which I tossed in the fire, and out popped this calf!” It is one of the Bible’s greatest, most humorous, and saddest lies; in short it is the lie of the would-be leader, trying to blame others, trying to win without responsibility. It is Machiavellian to the core.

Without further comment—no condemnation, no sarcastic laughter at the lie— Moses heads back up the mountain and entreats YHWH to forgive the terrible sin of the people. And, Moses continues, if YHWH is unwilling to forgive, then he demands that YHWH blot him out of the great book of life that YHWH has written. This can mean two things, and I suggest that both meanings are intended. First, it could imply that Moses would rather not live in a world where YHWH does not forgive sin; such a world would be uninhabitable. Second, Moses is offering his own life for the life of the sinful people. Both meanings are possible, and both are important. Rather than lie, or blame, Moses offers his own life, urging God to forgive the calf builders at Moses’s own expense. It is a splendid, unforgettable act of legitimate and genuine leadership.

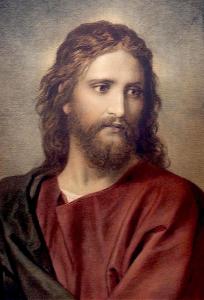

We Christians follow one who did precisely the same thing. Luke’s Gospel has the dying Jesus, agonized on that cross, forgive those who nailed him there, crying out that they were ultimately ignorant of their despicable actions. And there is the final definition of legitimate leadership. Remember John 15: “No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends,” not to mention one’s enemies, which Jesus would surely include. We need genuine leaders, all right, but not in the Machiavellian mode; we have a surfeit of those sorts of leaders now. We need leaders like Moses, like Jesus, but such leaders are rare. After all, those leaders too often resemble losers, not winners, seem to be weak, not powerful. Still, the basic question all leaders must answer is: what sort of leader will you be, Moses or Machiavelli?

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)