“Call now! Is there anyone to answer you?

“Call now! Is there anyone to answer you?

To which of the holy ones will you turn” (Job 5:1)?

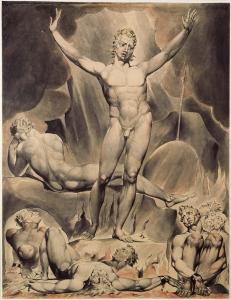

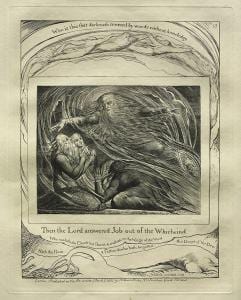

With this sarcastic jibe at the sufferer Job, Eliphaz, his so-called friend, dares Job to call out to any of the would-be “holy ones” for some sort of answer to his pleas for death or for replies to his demand for an explanation for his troubles, as he shouted his long speech of chapter 3. We know for certain that Eliphaz is convinced that there is only one Holy One who has created all things and who does all things, since he has already announced his certainty that Job is being punished by that God for some as yet unnamed and unadmitted crimes for which that God has punished Job with enormous loss and foul disease (see chapter 4). For Eliphaz, there can be no other “holy ones,” so his offer that Job turn to them is in reality merely a dark and cruel joke; only God can save Job, thinks Eliphaz, and only if Job admits his errors and returns to that God’s inevitable rewards for good behavior. Ironically, however, Eliphaz has triggered in Job an imaginative possibility that in fact there may be other holy ones that could be sources of help for him. As a result of Eliphaz’ suggestion, Job’s brain begins to boil with theological notions that are in the context of Israelite belief strange and dangerous. But Job is nothing but strange and dangerous in the ways his suffering, and confusion about its origins, have forced him to think about his tragic and horrific life.

We find three places in Job’s speeches where his unusual notions about possible “holy ones,” apart from and outside God are voiced. One of the basic claims of Israelite belief is to be found in their near-creedal statement about YHWH to be found in Deuteronomy 6:4: “Hear, O Israel: YHWH is our God, YHWH alone.” The famous verse might also be translated: “Hear, O Israel: YHWH is our God, YHWH is one.” In either case, the claim is that YHWH is alone, unique, one and indivisible. The role of God of the universe has been filled, and no one else need apply. Yet, Job, in his anguish, and in his conviction that that one God has suddenly turned on him and become his enemy, forces him to think very differently if he is to receive any answers to the questions of his miserable existence. The traditional view of the God of Israel has for Job become untenable. When the friends in turn demand that he ask God for relief from suffering, to call on God to relieve his pain, he finds that traditional door closed, since he is convinced that God is the cause and source of his anguish and pain, and thus cannot be the one who can help him. Hence, he imagines someone, something else. And those imaginings become increasingly wild and astonishing as the friends continue to harass and needle him and as God apparently continues to employ unremitting assaults against his life.

The first look at a third party in his dispute with the friends and God is found at Job 9:33-35. Leading up to the surprising idea of those verses, Job has accused God of unrestrained and ill-used power (Job 9:3-10), and indiscriminant sadism (Job 9:13-24). Then he whines again about the horrors of his life, wishing his pain would end (Job 9:25- 32). He then voices this amazing wish: “If only there were an (NRSV “There is no,” the grammar yields either reading) umpire between us, who might lay his hand on us both” (Job 9:33). The translation “umpire” is a good one for the Hebrew moki’ch. It is a participial noun form from the verb “to decide or judge.” It implies an impartial arbitrator, one who may judge a case without influence from either party, thus like an umpire in a ball game who “calls ‘em as he sees ‘em,” without influence or favoritism. Job dreams of such an umpire “who might lay his hand on us both (Job and God),” and who would “remove God’s rod off me, not let dread of God terrify him, so that I could speak without fear of God, because I know it is not like that with me now” (Job 9:34-35).

Job’s imaginative idea for such an umpire is almost immediately dashed when he returns to his certainty that his life is about to end at the hands of the cruel God in chapter 10. Job accuses God again of overt monstrousness against him, whose purpose was always to destroy Job, though it was God who first created him (Job 10:8-13). In the light of this horrifying God, there is certainly no umpire who could even the struggle, who could make a fair judgment against God’s malicious assaults.

The second place of Job’s search for a “holy one” where he might turn is found in Job 16:18-21. This is the first speech of the second cycle of dialogue speeches between Job and his friends, a speech that follows Eliphaz’ first second cycle address. The basic thing to note about this second cycle (Job 15-21) is that among the speeches of the friends there is now no hope for Job’s return to God; they are now only intent on demonstrating his unredeemable evil. In other words, their speeches have become only unrelievedly cruel, attacking Job with a darkening pitilessness. In that way, Job is further forced into a desperate search for some way to escape their attacks and the attacks of his God.

(18)“O earth, do not cover my blood;

let my cry for justice find no resting place.

(19)Even now, look! My witness is in the sky; my guarantor is on high.

(20)My friends are my (so-called) mediators, while my eyes pour out tears to Eloah.

(21)My guarantor will maintain the right of a warrior with Eloah, just as a human does for a neighbor.

Job here calls for a “witness,” a “guarantor,” a kind of heavenly defense attorney, whose role it is to stand toe-to-toe with God in a courtroom, bearing Job’s case directly to God, assuring that his case will receive a fair hearing in the divine court. This image appears to up the ante of the umpire that Job longed for in chapter 9. There he wanted an impartial figure; now he desires an advocate, one who can defend him against the unfair accusations of God. He demands that the ancient earth itself serve as witness to the reality that his cry for justice, echoing the ancient cry of the dead Able against his murdering brother Cain (Gen.4) will not be stilled, but will call forth a Joban defender, even if the accused has been slain by his adversary. Job’s desperation grows apace, but its final presentation is the most astonishing of all.

Job 19:25, embedded within the longer section, 23-27, is justly famous, made especially so by the soprano aria at the beginning of Part 3 of Handel’s ubiquitous “Messiah.” That oratorio, among the most sung of all choral pieces, particularly at Christmas and Easter, has fixed solidly in the minds of millions of listeners that what Job 19:25 refers to is either Jesus in a predictive way, or God in the Israelite context of the time of its writing. I find neither conclusion at all persuasive. The “Redeemer” of the verse can only be seen as Jesus, if one imagines that the Hebrew Bible is some kind of prefiguring of that first century man, 500 years prior to his birth. I cannot think like that as I read this text, nor can I in this literary context imagine that Job has God in mind as he recites 19:25. He refers here, I am convinced, once again to a third figure, a “redeemer” or “vindicator” (see the NRSV footnote). Bible translations have long capitalized this word, suggesting that they have already decided that it does in fact refer to a divine person, but all classic Hebrew letters are capitalized, so to single the word out for such treatment is to over read the word significantly. Besides, there is another way to hear this text.

The Hebrew word translated “redeemer/vindicator” is Hebrew go’el. The word has three possible meanings in the Hebrew Bible. There is a legal/social meaning, best illustrated in the book of Ruth. In the levirate marriage idea (Deut.25) if a man dies, his brother, uncle, cousin, or some other male relative is charged with marrying the widow in order to keep the male line alive and to provide the widow protection in a patriarchal society. Hence, Boaz marries the widow Ruth, and becomes thereby the go’el of her property and her person.

The second meaning is theological. 2-Isaiah 40-55 uses the word 9 times in various contexts to describe YHWH, the “redeemer” of exiled Israel. As I have already noted in the first of these essays on Job, 2-Isaiah and Job’s author were in dispute about the nature and purpose of YHWH as a result of the Babylonian exile. For Isaiah, the redeemer, the go’el, is certainly and unfailingly YHWH who is the unquestioned vindicator of the people of Israel. But I think Job has a completely different idea about the go’el.

The third meaning of the word finds its literary example in 2 Samuel 14:4-11, though more on the idea may be found in Numbers 35:12, 19-27. In ancient Israel, the notion of a “redeemer of blood,” a go’el, was developed in order to avoid wholesale slaughter of one group by another group, due to the murder of one member of the first group by a member of the second. In other words, if a member of group one is killed by a member of group two, an avenger of blood is appointed by the second group to avenge the killing, preventing group on group warfare. In the Samuel passage, the woman of Tekoa is deputized by Joab, David’s general, to convince the king that he has punished his son Absalom long enough and should allow him to return to Jerusalem. The woman tells a tale about the murder of one of her sons by the other, and the desire of her community to get revenge through the employment of the avenger of blood, the go’el. She begs David to intercede to prevent the killing of her only remaining son. Whether the story is a true one, or merely a ruse dreamed up by Joab, is not the issue. The function of the avenger of blood is made plain.

I suggest that Job uses this meaning of go’el in 19:25. What Job now demands is a “redeemer of blood” to solve the problem of his imminent murder by God. In short, he looks for the go’el to kill God to gain revenge for God’s unjust murder of Job. This is why Job demands that the accusations he has made against God’s completely unjust actions with regard to him be “written in a book,” or even better, “engraved on a rock with iron pen and lead forever” (Job 19:23-24), in order that when the go’el kills God, all will see that the murder was fully justified. This explosion of Job’s most vivid imagination may sound appalling and repulsive at first blush, but it may soon be seen that this God, the rewarding and punishing God, this mechanical dispenser of evils and goods, is a God that needs killing in order that a fresher way of seeing God, the real God of the universe, may be possible. And in our final essay in this series we will see a very different idea of God indeed, one that may help us think anew about just who it is we worship and adore.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)