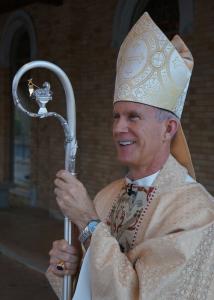

I’m teaching a class on Catholicism this semester, and, in an effort to jazz things up a little bit, we watch a video or two at the beginning of every class. A lot of those videos have come from the twin online stars of American Catholicism, Fr. Mike Schmitz and Bishop Robert Barron. Both speak in a Christocentric, biblical manner that is appealing to many evangelical Protestants, my students included. Bishop Joseph Strickland seemed to me to have less of an automatic appeal.

But when we watched a video that Bishop Strickland recorded before the recent Synod on Synodality, I was surprised by my students’ positive reaction. Schmitz and Barron both come across as pretty irenic. Strickland is a firebreather, notorious for affirming that one cannot be simultaneously a Democrat and a Catholic.

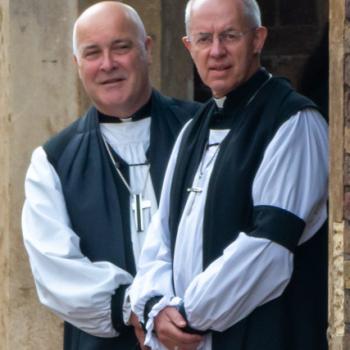

Bishop Strickland was also the local bishop here in East Texas until today when Pope Francis removed him from office. No reason was given, but he had been under investigation since an “apostolic visitation” of retired bishops this summer. I’m not an expert on canon law, and perhaps the official reason was something more mundane like Strickland’s refusal to fall into line on the Latin Mass, but surely his increasingly open attacks on the Pope were the underlying cause.

Strickland’s reach goes far beyond the Diocese of Tyler. The New York Times was at pains to point out how unimportant a position Bishop of Tyler really should be (his diocese is apparently “remote and relatively small”). His online audience was bigger than the sum total of all of the Catholics of East Texas.

A short side note: I’m completely aware that Tyler and Longview are no Dallas, let alone New York City, but they are also far from “remote.” Tyler is only an hour and a half from downtown Dallas and about an hour from the eastern outskirts of the DFW area (home base for Ruth Graham, the NYT’s excellent religion correspondent who co-wrote the article). By NYT standards, the Diocese of Tyler might still qualify as remote, but it’s certainly not geographically small. It covers 33 counties and 23,443 square miles, making it substantially bigger than Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island combined (by my math, that’s 17,642 square miles–maybe the writers had a different meaning of “small” in mind?). [A Catholic friend has told me I’m being obtuse here: “size” apparently means churches and congregants, not acreage, when you’re talking dioceses].

What’s intriguing about Joseph Strickland for me is that he is a native East Texan, raised in the small city of Atlanta, in between Texarkana and Lady Bird Johnson’s hometown of Karnack, right next to the three-way junction of Arkansas, Louisiana, and Texas and about an hour from Shreveport. This is not a very Catholic part of the world. In Cass County, where Strickland was raised, the Catholic Church claims only 303 adherents out of a total population of 28,454 (just over 1% of residents).

I had the chance to talk with Bishop Strickland last year when I was working on an article on evangelical-Catholic relations. What I found fascinating about him was the way he related himself to the conservative culture of East Texas. He told me that as a kid he experienced a fair amount of anti-Catholicism from peers who were taught to hate Catholicism. That’s now mostly faded, but it clearly shaped his outlook.

Strickland is obviously aware that most of his native region is not likely to set foot in a Catholic church, but he sees his conservative activism, especially his pro-life advocacy, as a kind of bridge to the conservative Protestants who dominate the region. He told me that Tyler’s 40 Days for Life campaign, for example, a pro-life campaign, has received quite a bit of support from evangelicals in the area. He gets fan mail from admiring Protestants who appreciate his verve and sympathize with his bluntness.

He described himself to me as “sort of an evangelical Catholic.” I think he meant this in a bit of a different way than someone like Bishop Barron, who has made the term a hallmark of his ministry. For Barron, being “evangelical” means finding a middle way between “beige” liberalism and extreme traditionalism through the New Evangelization (an emphasis on reevangelizing the secular world that was a major focus of John Paul II).

For Bishop Strickland, it means something more like being a sold-out believer in the traditional supernatural Catholic message and a fighter in the public sphere against abortion and homosexuality. He is “evangelical” in the sense that many American evangelical Protestants seem to agree with him on much of this (minus some fairly important theological points of emphasis).

Strickland’s fierce conservatism was, as strange as it might seem outside of the Piney Woods, actually (at least in his mind) a path to local ecumenical cooperation and engagement with non-Catholics. Bishop Strickland will now presumably be replaced by a more demure bishop.

The polemics will no longer come with a diocesan seal, but I’m guessing Strickland will keep his Protestant fans. And maybe I’ll find a way to meet with the next bishop to find out how a more vanilla Catholic leader plans to engage with the evangelicals of East Texas.