Same-Sex Blessings in the Church of England

Unlike many other Anglican churches in the western world (the Episcopal Church, the Anglican Church of Canada, and so on) the Church of England has not, up to this point, embraced same-sex marriage, the ministry of non-celibate gay and lesbian clergy (at least officially), or (until very recently) church blessings for gay couples. Despite being the established church in a nation that embraced gay marriage over a decade ago and where only 13% of the population considers same-sex relationships morally wrong, the Church of England has not officially walked back its commitment to Lambeth I.10, a 1998 resolution “rejecting homosexual practice as incompatible with Scripture.”

I’ve been loosely following the debate over sexuality in the Church of England and global Anglicanism since I was a kid. I left the UK and stopped attending Anglican churches when I was 8, but every time I went back to England, I’d find myself struggling to understand the most recent developments from my relatives.

This year, the debate entered a crucial stage. A years-long consultation known as Living in Love and Faith (LLF) culminated in a decision by the bishops to introduce same-sex blessings in the Church of England. Because the bishops claim that this liturgical step does not involve a change in doctrine, they argue that it does not require laborous doctrinal and legal changes to the Canons of the Church of England but instead can be approved for “experimental use” immediately under Canon B5A simply at the discretion of the bishops.

This also avoids the necessity, for now, of a two-thirds vote of all three houses of General Synod, which in its current make-up includes a large minority of lay and clergy members of synod who oppose any changes to the historic practice of the church. A vote to approve an amendment by Bishop Stephen Croft of Oxford to begin experimental stand-alone services of blessing won the House of Laity by only one vote (99-98), and both the House of Clergy (101-94) and House of Bishops (25-16) also had large numbers of dissenters.

A two-thirds vote would have obviously failed, and the leaders of the LGBT lobby will hope that the next General Synod election in 2026 leads to a substantially reduced orthodox minority. Whether that happens will likely depend on how conservatives respond in the next two years. If they can stomach the experimental blessings for now, maintain relative unity, organize politically as they did at the last Synod election in 2021, and avoid the temptation to withdraw to the shadow organizations that have formed to offer relief (the Anglican Network in Europe and Anglican Mission in England), then it seems likely they could prevent any formal liturgical (and certainly any official doctrinal) changes for the foreseeable future.

I’m not an expert on Anglican politics, though, and I wouldn’t have gone into such detail if I didn’t think this background was quite important to my broader focus in this post.

An Anglican Evangelical United Front?

One of the quite remarkable outcomes of the LLF process has been that it has driven orthodox Anglicans of different stripes together. This includes traditional Anglo-Catholics, but most of the co-belligerents have been evangelicals of different kinds.

The Church of England is incredibly factional and has been throughout its history. Starting in the late seventeenth century, the major split was between the Latitudinarians and High Churchmen. In the nineteenth century it was between the Evangelicals, the Broad Churchmen, and the Anglo-Catholics. In the twentieth century, each tradition spawned numerous sub-tribes: liberal catholics, open evangelicals, charismatics, and so on.

Today there are three major evangelical groupings in the Church of England: the conservative evangelicals (think John Stott), the charismatics (think Nicky Gumbel), and the open evangelicals (think N. T. Wright). They are defined by their own journals, conferences, mission societies, inquirers’ courses, and theological heroes, and disagree on issues like gender and the experience of the Holy Spirit, as well as, to a lesser extent, biblical authority, worship, and church politics. They have historically agreed on sexuality, although not necessarily on its relative significance or the most strategic path forward.

The Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, is a product of Holy Trinity Brompton (HTB), the charismatic epicenter of the Church of England. Even though Welby has strayed from his roots, embracing a more eclectic set of Anglican practices and, at least in recent years, liberalizing on sexuality, he has still relied heavily on HTB for efforts at church revitalization. And, although their flagship Alpha Course is now used across denominations, HTB has become deeply embedded in official renewal efforts within the Church of England.

As a result, the decision of HTB and its leadership to enter the ranks in the orthodox fight against the LLF proposal was a significant step. Evangelical signatories to a protest letter this summer included the (charismatic) leaders of New Wine and the HTB Network, as well as the pan-evangelical Evangelical Group of the General Synod (EGGS) and the Church of England Evangelical Council (CEEC). Among the most vociferous online opponents of the plan is Ian Paul, an open evangelical. In addition, given the paucity of conservative evangelicals in the episcopate, most of the bishops who have been critical of the LLF process are either charismatic or open evangelical.

Given the unanimity of official Anglican evangelicalism (EGGS and CEEC) against LLF, it was somewhat surprising to see the publication of an open letter in early November signed by over 600 “evangelicals” from a newly formed group called Inclusive Evangelicals that professed full endorsement of LGBT inclusion and same-sex blessings. In the statement that accompanied the open letter, the leadership of the group claimed that this represented “a significant change in the political landscape for the debate over Living in Love and Faith.” The effort was clearly to demonstrate that the conservatives did not speak for evangelicalism at large, and it fit with a broader strategy to paint opposition to LLF as a hallmark of a conservative evangelical minority rather than the evangelical mainstream.

Members of General Synod voting at its February meeting (Embed from Getty Images)

I’m not in a position to judge how “evangelical” the signatories of the Inclusive Evangelical statement are. A handful of the founding members were among the small minority of EGGS synod members who were forced out when the group made its traditional stance on sexuality binding. Others are generally understood to be “liberal catholic” in outlook. Plenty more probably have some kind of conventional evangelical connection, sometimes in the past. In their own statements, the group seems more interested in problematizing evangelical identity than in defining it. Mark Vasey-Saunders says that “evangelicalism has rarely been more fractured and multi-faceted than it is today.” Paul Roberts argues that homosexuality is just one of a number of issues (along with baptism, predestination, and eschatology), in which genuine evangelical disagreement persists.

A Question of Evangelical Identity

What’s interesting to me is the political choice of these campaigners to identify as “evangelical” in the first place. This stands in dramatic contrast to the American scene, where, by and large, the figures who have moved from a traditional evangelical stance on sexuality to an LGBT-affirming one have done so as part of an exit from “evangelicalism.”

Churches in the US from evangelical backgrounds that have become fully LGBT inclusive like City Church in San Francisco, Pearl Church in Portland, Reservoir Church in Cambridge, GracePointe Church in Nashville, and Blue Ocean Church in Ann Arbor do not identify as evangelical, even if their worship style still bears an evangelical imprint.

Brandan Robertson, who emerged from Moody Bible Institute in 2014 to become a vocal proponent of gay inclusion quickly pivoted from a short-lived campaign to change the evangelical church from within (“Evangelicals for Marriage Equality”) to metamorphoze into a self-described progressive Christian and mainline Protestant pastor. David Gushee, a formerly evangelical ethicist at Mercer University, who made headlines when he changed his mind on sexuality (also in 2014), proceeded to write a book called After Evangelicalism.

This is not to say that all American would-be “affirming evangelicals” become jaded exvangelicals. Although I have no idea if he identifies as an evangelical, Matthew Vines of the Reformation Project (founded 2013) has worked hard to make his program appealing to evangelicals, with a statement of faith clearly geared to Bible-believing Christians and cohorts that equip “advocates for LGBT inclusion in the non-affirming church.” That said, even if he appeals to evangelical buzzwords, Vines’ project is framed in ecumenical terms, not explicitly as an effort to transform the evangelical church.

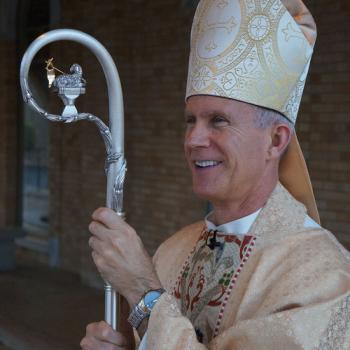

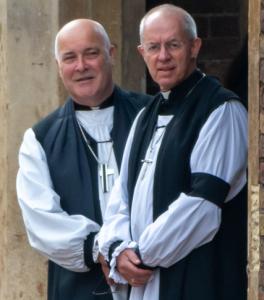

Justin Welby crowning Charles III this spring (Embed from Getty Images)

The contrast between the American and English scenes is illustrative of the very different ecclesial and cultural politics of these countries. In the Church of England, being “evangelical” allows pro-LGBT campaigners to reduce the power of an apparent evangelical consensus in favor of traditional sexuality. In the United States, especially in the progressive cities which tend to produce pressure towards LGBT inclusion on some evangelical leaders, being explicitly “evangelical” ties a church to unwanted cultural baggage that can sink an urban church plant. As a result, even conservative churches increasingly avoid the term and newly progressive congregations certainly feel no compunction about erasing any memory of being amorphously connected to figures as outré as John Piper or Franklin Graham.

In a sense, this is simply a reflection of the traditional divide between state-church England and free-market America. In the American free-for-all of religious competition, marketing to potential consumers appears to be the chief focus. In the English state church, maneuvering for political impact among religious power-brokers like the bishops takes precedence for activists. Meanwhile, the coherence of evangelical identity becomes ever more endangered.