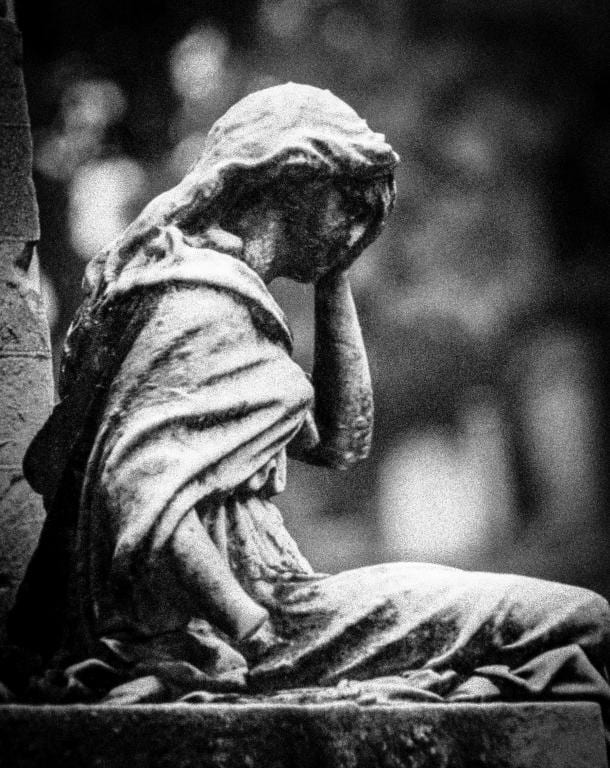

Grief. Source: Wikipedia Commons

Once, in trauma therapy last year, my counselor mentioned to me that I seemed to be grieving.

I don’t remember what I was discussing, but I remember feeling shocked and bemused at what she said. I didn’t think the emotions I was having were grief. I thought they were anger and irritation.

But here’s the thing: anger and irritation are my go to emotions, you could say.

When other emotions feel too threatening, the anger and irritation take over. They feel safer. I can use them to make a shield around me, to protect myself. When other emotions—empathy, fear, grief, loneliness, even joy—feel too vulnerable, the anger and irritation rise up and protect me. They keep me safely cocooned inside.

It’s a coping mechanism. It was necessary for a lot of years. It sometimes still is.

But not always.

Recently someone dear to me questioned the morality of my writing openly and publicly about the abuse my family faced from my father. And those words stung. A lot.

They more than stung. They sent me into a panic. And my anger and irritation took over.

I wrote an angry response. It was powerful to write those words. And it was empowering.

But it wasn’t vulnerable. It wasn’t loving. And this person deserves my love.

So I spoke with many trusted mentors and friends, and after a little more than a week, I rewrote that response. My trauma therapist told me to sit down and write what I wanted to say, and to be myself. I said that sounded scary, and I’d rather swear and throw things. She told me to do both.

I think, reflecting on it now, it was scary because I had to be vulnerable. I couldn’t let my anger shield me this time. I had to be raw, which is very, very scary when someone has questioned my decisions in terms of healing from my abuse and trauma.

I was pondering this tonight, anger and grief and loss.

I read this week’s Dark Devotional at Sick Pilgrim. In it the author, Deanna Emge, describes her old parish, and it resonated hardcore with my own past:

We had had large families and homeschooled and refused to hold hands during the Our Father at Mass. Because we did all the right things, we considered ourselves faithful, and concluded that others who didn’t do all the right things were unfaithful. We set ourselves apart.

Yeah. We did that too.

But then this author switches it, and talks about death. She pondered, at this funeral, the way that death makes us all equal, I think, as nothing else can.

Perhaps death is like that. Who’s right and who’s wrong is put aside. Us versus them loses its attraction. It’s now about us.

This thought has sometimes slipped through my strong walls of anger and irritation, forcing me to face these questions. Was my father wrong? Was I truly right? Does it even matter?

And then the anger jumps in and smashes those thoughts out, because they are unsafe. And for a victim of religious, psychological, and emotional abuse rife with intense gaslighting, these thoughts are usually unsafe. Because they can plunge us into the same self-doubt that our aggressor carefully groomed into us and send us right back to the guilt and paralyzing self-hate.

Yes, reality is that my father was wrong. And that I was abused, my mother was abused, my brothers were abused. I’m not letting that voice back in. Not today, Satan.

But today, this guest writer at Sick Pilgrim slipped past my anger shield and in a rare moment of calm, I was able to ponder some things. Will I be able to mourn my father when he dies? At his end, will his actions pain me less? Will I finally be able to grieve the man he could have been, the father my brothers and I were owed, the husband my mother deserved?

Will I be able to forgive him, perhaps?

Before I left Spain, I spent a few days in another world (so it seemed) with my friend Silvia and her family. We went to visit her grandparents’ home in a tiny village called Josa where her mother was born. Then we went to El Monasterio de Pierdra, a breathtaking park with at least seven waterfalls. At the top of one of them, we climbed down steep steps carved into the rock and explored a giant cave behind the waterfall and pretended we were in Neverland or Narnia.

Later that week I messaged Silvia.

I finally realized that spending time with your dad was wonderful but bittersweet. He reminds me a lot of my dad, his personality and even appearance. So it was like spending some time in a fairytale with my dad as he could have and should have been–kind and loving, if sometimes grumpy and difficult, choosing to live a life not consumed by fear.

So perhaps, in time, the anger will loosen its protective hold, and the grief will reach me more, bit by bit.

I’m not sure I’m ready for that yet. But I’m beginning to look forward to the peace and release I believe it will bring.

Image Credit: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Grief_(10846664293).jpg