I’ve been thinking a lot lately about an e-mail exchange from 20 years ago.

In 1997 I was on an animal rights mailing list, “chickadee-l”. Looking back on conversations there, I can see early stirrings of problematic ideas that plague today’s social justice movement.

There is one bit of dialogue that still astounds me two decades later as a crystal clear statement of a very wrong idea. As this was a closed list, I won’t identify my correspondent; I’ll just say that he wasn’t a random netizen but had academic credentials in philosophy, and is now the author of two books and several papers in the field.

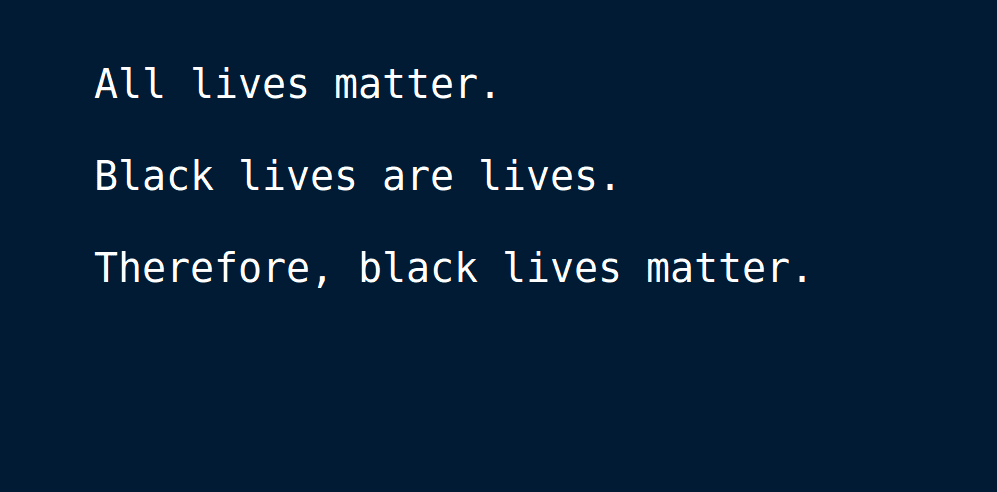

In a discussion about ethical theory and the nature of rights, my correspondent wrote:

I think of myself as a radical, that is, one committed to the abolition of structures of domination, exploitation and oppression. For me, politics is prior to ethics. That is, the primary question is “whose side are you on, the exploiters or the exploited?” Once we decide that, then we construct ethical theories to try to explain our decision.

Now, I also think of myself as a radical. I believe that we must be ready to question our fundamental assumptions in order to get to the root (radix) of a problem and truly solve it. And as a philosophical anarchist I am opposed to hierarchical power structures and exploitation of all sorts.

But these are positions I have arrived at through reasoned analysis, by trying to develop a theory about what is best that is in concert with disciplined critical thinking, ethical intuition, and empirical fact, and then trying to apply that theory to specific instances.

To put it briefly, I start with the axiomatic observation that my own suffering is a bad thing, something to be reduced and avoided. Critical thinking and empirical experience inform me that that other sentient beings experience their lives in a way similar to that which I do. Their suffering is similar to mine, and is therefore also something to be reduced and avoided.

Now, because I am an imperfect logician trying to comprehend the universe with three pounds of fatty meat in a bony cage, I sometimes get this process wrong. I fall for fallacies, I get dragged along by immediate passions rather than navigating by clear and sober reflection. My ego gets bruised and I close my eyes to important points of fact or logic. I get lost in the weeds following an argument.

But the goal is to use reason rather than gut feeling as my guide in finding the best way to live.

In contrast my correspondent suggests that we ought to pick a side based on our feelings of sympathy, and then seek justifications for our choices. In one of his books, he describes the idea that reason should dominate emotion in ethical decision-making as a “patriarchal norm”. Let your heart and your gut lead you to a verdict first, and then let your intellect conduct a sham trial after.

(Dismissing reason as “patriarchal”, assuming it to be somehow masculine and emotion to be feminine, strikes me as sexist bullshit; but that’s a tangential rant.)

It’s all very well to declare that we should be on the side of the exploited rather than the exploiter. Our rationally informed sympathy lets us put ourselves in the shoes of those who suffer, those who are disadvantaged or exploited or cast out. It tells us that we are not fundamentally better, not more deserving of basic rights, than they are — indeed it tells us that someday we may be in their place. And so we have a motivation beyond simple gut feeling to act for justice.

But the world is rarely simple. Few conflicts are between a clear exploiter and exploited. More often we face a conflict between individuals or groups who are both being exploited or oppressed by parties outside the conflict. Sometimes they are both being manipulated by the “let’s you and him fight” strategy that is so often used by the powerful, sometimes it is two oppressed groups fighting over scraps.

A look at the news on any given day will provide examples. A Holocaust survivor who backs the ethnic cleansing of Arabs from Palestine to create and expand the state of Israel. A Muslim refugee, victim of colonialism and Islamophobia, who wants to deny equal rights to women. A working class white guy, victim of neoliberal economics and classism, who is infected with racism. A black professional, victim of racism, who is bigoted against poor rural “white trash”. An abused woman, victim of domestic violence, who thinks that transgender women are really men playing some long con in order to abuse women.

In a rational system, we would try to help each of these people secure their own rights to the extent that doing so does not infringe on the rights of another. But in the rising “victim culture” each presents their grievance as a way to raise their moral status and seek favor from those in power. As Campbell and Manning put it, they “advertise their oppression as evidence that they deserve respect and assistance” from the bosses.

But the fact is, everyone is suffering. Some suffering is more obvious, some is hidden; some has causes that are external or historical, some is self-inflicted; some sufferers tug at our heartstrings at first glance, some immediately repel us as vile.

The universality of suffering is the First Noble Truth for good reason. And so in the complexity of the world, it takes more than emotional sympathy with the sufferer to understand how to best proceed.

And more than being inadequate, appeal to passion over reason is dangerous. Emotion isn’t just a matter of warm fuzzy sympathy. Putting emotion over reason means putting fear and anger over cool-headed reflection. That is a highway to authoritarianism, one of the hallmarks of fascism, and so its presence in modern “social justice” movements is very concerning.

Let me be clear: I believe that many forms of injustice persist in our society and that we can do a much better job of trying to fix them, through both public policy and our social norms. But that does not mean that everyone who wraps themselves in the social justice label is helping with the problem.

It doesn’t even mean that everyone who wraps themselves in that label is actually motivated by a genuine desire to help, as opposed to a desire for power, for attention, or emotional catharsis.

As a current example of this problem, we might take the way that Evergreen State College biology professor Bret Weinstein has been branded a racist and targeted with disruptive protest and threats — a Dionysian frenzy, violently drunk on self-righteousness.

No disrespect to Dionysus; he and I have an understanding, a working relationship. But it is because I know him that I know that social justice is not a job to which you send a god whose followers have a reputation for tearing people to shreds with their bare hands. And watching protesters excite each other to higher and higher levels of frenzy, I am reminded of nothing as much as the Maenads — “the raving ones”.

Weinstein committed two sins against the orthodoxy of campus social justice: he questioned an affirmative action plan for faculty that would require an “equity justification” for each hire, and he objected to a “Day of Absence” event that demanded white students leave campus for the day.

At no time, so far as I can tell, has he said or written anything claiming that people of different races do not deserve equal social and legal rights. Nor has he claimed that racism is not a serious social problem. He merely disagreed about the best way to handle that problem.

If we are basing our ethics and politics on reason, then it’s clear that reasoned discussion — perhaps adversarial, perhaps even heated, but rooted in mutual respect for logic, fact, and a belief in the good intentions of one’s interlocutor — is the way to handle that disagreement. Maybe Weinstein is right, maybe he’s wrong, but we can have a conversation about it that assumes good intentions on both sides.

But if we are basing our politics on gut sympathy, then we can blame Weinstein for not displaying and acting on the proper emotions. If he disagrees he must not merely be misinformed or guilty of faulty logic, he must be heartless, a psychopath, emotionally and spiritually crippled.

Another recent example is the response to Rebecca Tuvel’s paper “In Defense of Transracialism” in the feminist-philosophy journal Hypatia. “Transracialism” is the idea that there is some sense in which the claims of people like Rachel Dolezal to identify as a race other than which society assigns them based on ancestry, could have some merit in some cases. It’s not my objective to defend or refute that idea here, but only to defend the idea of defending or refuting it with reasoned argument.

Journalist Jesse Singal explains,

Anyone who has read an academic philosophy paper will be familiar with this sort of argument. The goal, often, is to provoke a little — to probe what we think and why we think it, and to highlight logical inconsistencies that might help us better understand our values and thought processes. This sort of article is abstract and laden with hypotheticals — the idea is to pull up one level from the real world and force people to grapple with principles and claims on their own merits…

But rather than engaging on that abstract level, writing papers disputing Tuvel’s thesis that “similar arguments that support transgenderism support transracialism” and arguing it out in the pages of peer-reviewed journals, critics fired up the Internet Outrage Machine, claiming that merely publishing the paper was causing harm (we’ve discussed this conflation of “upset” with “harm” before), pressuring the journal into issuing an apology, and sabotaging Tuvel’s reputation with false claims about the article.

(There is some irony here, in that Hypatia of Alexandria was Neoplatonic philosopher who was murdered by outraged Christian zealots.)

How has this idea that outrage is a workable substitute for reasoned debate gotten such a grip on academia, and moved out into broader society? Weistein points to the creation of “justice-oriented fields” in the 1960s and 70s:

Rather, the protests resulted from a tension that has existed throughout the entire American academy for decades: The button-down empirical and deductive fields, including all the hard sciences, have lived side by side with “critical theory,” postmodernism and its perception-based relatives. Since the creation in 1960s and ’70s of novel, justice-oriented fields, these incompatible worldviews have repelled one another. The faculty from these opposing perspectives, like blue and red voters, rarely mix in any context where reality might have to be discussed. For decades, the uneasy separation held, with the factions enduring an unhappy marriage for the good of the (college) kids.

Both the hard sciences and the liberal arts are based on the criticism of ideas. If you’re going to publish a paper with a new hypothesis about sub-atomic particles or about Shakespeare’s plays, you can expect it to be disagreed with, criticized, and debated. Truth is the goal, the asymptotic end product of the process. If your ideas about science or the humanities are rejected by scholars you will be called wrong, you may even be called intellectually inadequate, but no one will question your worth as a human being.

In contrast, fields like gender or race studies are rooted in axioms about the nature of justice and the existence of injustice, axioms that are politically charged by their very nature. The only permitted debate is about how to advocate and actualize those axiomatic ideas. If you come too close to these fundamental assumptions and are rejected by the academic power structure, you can be branded a moral failure.

This is not to say that we shouldn’t be investigating these fields! But their sensitive nature makes it more imperative that discussion of race and gender be grounded in the sort of disciplined thinking and open dialogue that (should) underlie sociology, anthropology, and philosophy, rather than emotion-driven charges of moral failing.

You can keep up with “The Zen Pagan” by subscribing via RSS or e-mail.

Please consider supporting this blog with a donation or purchase. Buy a book, or see The Zen Pagan Merch-o-rama for t-shirts, mugs, posters and prints, and stickers designed by yours truly.

I will be performing two sets of music at the Free Spirit Gathering in Maryland next week, and presenting workshops at the Starwood Festival in Ohio in July.

If you do Facebook, you might choose to join a group on “Zen Paganism” I’ve set up there. And don’t forget to “like” Patheos Pagan and/or The Zen Pagan over there, too.