Akira Kurosawa’s famous 1950 film Rashomon centers around four conflicting accounts of the murder of a samurai and the rape of his wife. The film does not show one account as truthful and the others as lies, but dwells on the ambiguity and ultimate unknowability of truth.

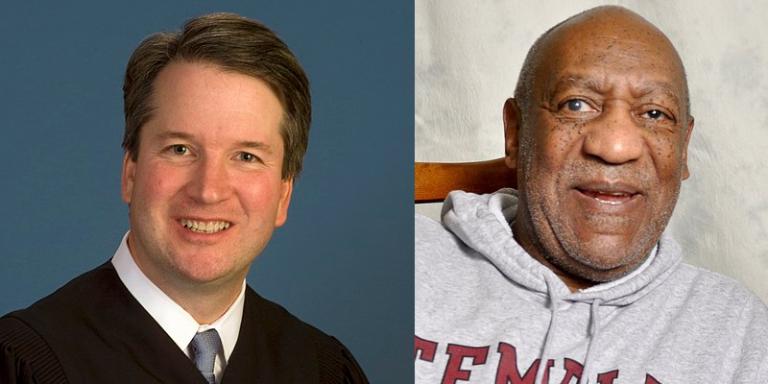

Rashomon leapt to mind when the controversy around the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court hit such a fever pitch that two men independently came forward to the Senate Judiciary Committee, to each claim that they, not Kavanaugh, were the perpetrators of the alleged 1982 assault on Christine Blasey Ford.

What the hell?

Maryland has no statute of limitations on felony sexual assault, so these men are opening themselves up to criminal prosecution with their claims.

Are they deranged attention seekers? Are they doing some sort of conservative “I’m Spartacus!” moment? Are they trying to obscure the question of Kavanaugh’s guilt in order to move his appointment forward, even at the cost of possibly going to prison themselves? Are they men who assaulted women around that time in similar circumstances, but aren’t sure who they attacked, and genuinely think they are guilty here?

Keyser, in other words, has a certain memory of her life, but she is willing to believe that her friend Ford’s memory of Keyser’s life is more accurate than her own. I’m not saying that she’s wrong to do so, mind; but it is a remarkable example of how thin our reality is.

Whatever else comes out of this, whether Kavanaugh is confirmed or rejected, whether some future finding exonerates him or proves his guilt or he just goes on for the rest of his life with credible but unproven allegations hanging over him, it underlines the complexities of memory, human motives, and truth, and reminds us of the need to be humble in the face of such questions. As an exchange in Rashomon puts it,

Commoner: …Out of these three, whose story is believable?

Woodcutter: No idea.

Commoner: In the end, you cannot understand the things men do.

There’s some irony that this comes at the same time that Bill Cosby, formerly one of the most widely admired men in the United States, has been sentenced for multiple rapes.

The Cosby case illustrates something important about how most rapes occur. The typical rapist is neither the “rapist in the bushes”, the violent perpetrator appearing from nowhere, nor the “date rapist”, the ordinary guy who is confused by “rape culture” about the limits of consent. That’s not to say such attacks do not occur! Any awful thing you can think of that one human being might do to another, has probably occurred many times.

But most rapes are perpetrated by deliberate, repeat predators. And like all predators, the rapist is well-camouflaged in his (or sometimes her) surroundings. In the case of the rapist, their camouflage is not a matter of stripes or colors but of social standing.

Kavanaugh’s defenders say “he’s not that sort of man”. But we would have said the same about Cosby when he was at the height of both his rape career and his acting one. If we can see that someone is “that sort of man”, he won’t have the opportunity to commit rapes. A successful bank robber does not walk down the street wearing a domino mask and carrying bags with dollar signs on them like some cartoon; a successful serial killer does not go around whetting his knives and cackling manically. A “successful” rapist does not look or act like our stereotypes of rapists.

There are now multiple allegations against Kavanaugh, in the pattern of a deliberate, repeat predator; yet, they come in a context where people are confessing to crimes they did not commit, raising a great fog. If I were going to bet money on a divine revelation of the truth of the allegations, I’d bet that he was guilty; yet I have to admit my own biases against him for his judicial positions.

Whether the allegations are true or not, it’s clear that the Democrats are (somewhat hamhandedly) exploiting them for political purposes — yet what else could the Republicans have expected, after blocking Obama’s nomination of Garland? They made Supreme Count nominees a game of hardball, and escalation was inevitable. We can expect that the next nomination, whenever it comes, will only be more contentious.