As I sit down to write this, a friend of mine — not a close friend, but a friend — lies in hospice care, dying. Dawn and her partner John (no last names as I do not know how “out of the broom closet” they are) are festival friends, people I would see at Starwood most years, chat with a bit, exchange social media pleasantries. I do not claim the privilege of knowing them closely, but I know them; and as she lies in hospice this Samhain time, reading John’s updates on Facebook, sharing in a measure of his grief, puts me more in mind of the season than most years.

When The Zen Pagan first started as an occasional installment of the Agora group blog, my first piece introduced the Bodhisattva Jizo, “Earth-Store” or “Earth-Womb” Bodhisattva. Jizo is his/her Japanese name (there was a gender switch along the way); they are known as Ti-tsang in Chinese, Kshitigarbha in Sanskrit, and Ji Jang Bosal in Korean.

(I will refer to Jizo as male for the rest of this article, as this is the manner of most Japanese depictions; but I want to also acknowledge the differing gender interpretations of “his” counterparts in other cultures.)

Jizo was never that big in Indian Buddhism. He made a bit of a name for himself in China, but it’s in Japan that he made it big. He is seen as a protector of children and of travelers, with statues and small shines often found out along the road.

But he is not just a protector of the sore-footed traveler along Japan’s paths and roadways. He protects all who travel the six realms of existence which traditional Buddhism postulates: the human realm, the animal realm, the world of hungry ghosts, the hell realms, the realms of the ashuras (titans or wrathful demigods), and even the distracting pleasure realms of the gods.

But he is not just a protector of the sore-footed traveler along Japan’s paths and roadways. He protects all who travel the six realms of existence which traditional Buddhism postulates: the human realm, the animal realm, the world of hungry ghosts, the hell realms, the realms of the ashuras (titans or wrathful demigods), and even the distracting pleasure realms of the gods.

Jizo is especially the protector and redeemer of those in the hell realms. The staff he is portrayed carrying is not just a walking stick, but pries open the gates of hell; the jewel or lantern shown in his other hand lights the way. In Buddhism, even damnation is not permanent.

Jizo’s great vow is that he will not enter Nirvana so long as any being is in hell – an “I am not free so long as any person is enslaved” sort of sentiment. No sentient being will be thrown away, left behind; we all make it to enlightenment, though it might take billions of years.

Somewhat as many practices for the dying in Christianity ask the intervention of the Virgin Mary and of saints and angels on behalf of the dying person, there are practices in Mahayana Buddhism that appeal to Jizo for aid. I especially remember reading the account of a Buddhist prison chaplain working with a condemned man, who advised him to chant Ji Jang Bosal, Jizo’s Korean name, at his execution.

As Zen Master Soeng Hyang said, “Chanting Ji Jang Bosal after someone passes away helps open your heart so that the line of demarcation between life and death fades, and what’s left is intuition and intimacy. Then it’s not just about you and your [loved one].”

As Zen Master Soeng Hyang said, “Chanting Ji Jang Bosal after someone passes away helps open your heart so that the line of demarcation between life and death fades, and what’s left is intuition and intimacy. Then it’s not just about you and your [loved one].”

Death is the great mystery, the undiscovered country, the unavoidable confrontation with the boundaries of who and what we are. Perhaps the greatest and wisest of us can sit directly with that mystery and let the grief just happen, like a leaf falling from a tree. But most of us need some form to our practice.

Chanting is an excellent practice. It can be done with the outer or the inner voice. You might chant his Korean name, “Ji Jang Bosal”; or the Japanese “Namu Jizo Bosatsu”; or the English eqivalent “Homage to Jizo Bodhisattva”; or an English phrase like “I take refuge in Jizo Bodhisattva”.

If you prefer something a step more esoteric, the traditional dharini for Jizo is (in Japanese) “Om Ka Ka Kabi San Ma Ei Soha Ka.” A dharini is a set of syllables without direct literal meaning, usually longer than a mantra. “Om” is familiar to us; “ka” is the “seed syllable,” representing the deity; “soha ka”, the equivalent of the Sanskrit “svaha” which you might know, is an exclamation I have seen translated as “so be it”, “may good arise from this”, “welcome”, “halleluja”, or even (in Beat poet Phillip Whalen’s rendering) “o mama!”.

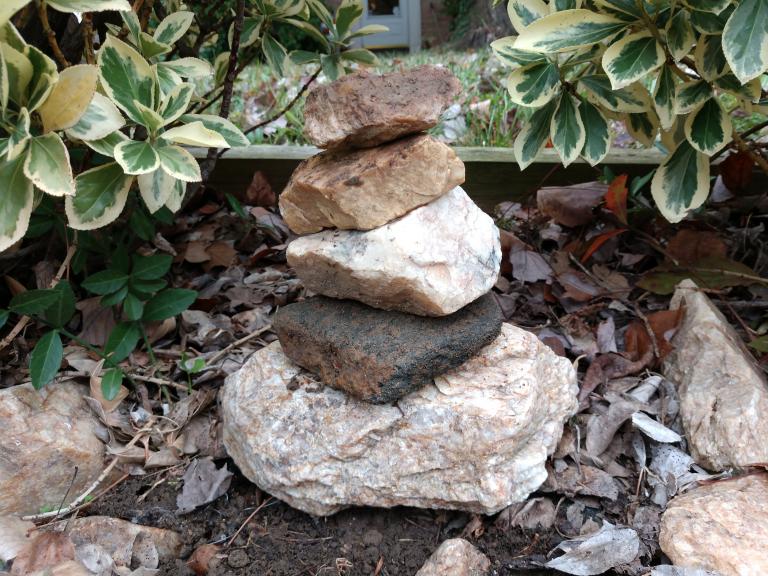

For a more physical practice, there is a tradition of building small stacks of stones in homage to Jizo. This comes from a story about the afterlife of children who die young. According to the legend, the spirits of these children are stuck on the banks of the river Sai, a sort of Buddhist version of the river Styx. Since they died young they had no opportunity to accumulate enough merit to move on, and so they are condemned to stay on the riverbank and pile up stones to build little stupas — which are knocked down by demons every evening. Only Jizo offers them protection and aid. With this little stone stacking ritual, we dedicate our merit — our energy, our “good karma”, our positive intentions — to the departed.

While the legend is about children, certainly we can all use a little boost to our merit.

(A note: please do not stack stones taken from the waters of a river, stream, or lake; moving them can disrupt the underwater ecosystem.)

(A note: please do not stack stones taken from the waters of a river, stream, or lake; moving them can disrupt the underwater ecosystem.)

I do not know if the Jizo stone-stacking tradition is directly related to the gorinto, the “five-ringed tower” of carved stones used in Japan for memorial purposes, where each stone represents one of the five elements (earth, water, fire, air, and void), but I find it good to do such stone-stacking in fives. (Of course that also appeals to my Discordian side, as a reminder that all things happen in fives.)

And so here at Samhain I say Namu Jizo Bosatsu, and I chant the dharini, and I stack some small stones at the hedgerow in front of my house, and I tend to the Jizo statue in my garden, for Dawn and John and for all who have passed and for all who grieve.