I am about to deliver an opinion which may shock and upset some.

An opinion about a topic of much current interest and discussion, but which does not fit either of the trends I see emerging in how people talk about it. An opinion which seems to be singular and unique, perhaps not shared by anyone else.

Netflix’s adaption of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman is…okay.

Good, but not as excellent as it might have been. “Television worth watching”, as the old slogan had it, but not the best thing to appear on my screen over the summer. (I have to give an overall higher mark to Season 3 of Love, Death, and Robots.)

There are some A+ elements, some moments as good as anything put on film or video. But there are some things that should have been better, flaws ranging from the aggravating to the disappointing. It averages out to perhaps a B+, a good job but I can’t concur with some of the superlatives going around social media

Let me be clear that I am a drooling fanboy of the original graphic novels; I’ve written that we may eventually see Gaiman’s Endless take their place as a religious pantheon as valid as any other. I discovered the stories early on, in about 1990 or 91, and it’s been nice to be an early adopter and watch others pick up on Gaiman’s work.*

So my beefs with the adaption are mostly in comparison with the original comics. If you’ve never read them, I’ll leave it to you to decide if you should do so before viewing the adaption and run the risk of disappointment in the Netflix version not living up; or view first, than read, which has the risk of cluttering up or spoiling your response to the books. I’m an “always read first” guy, myself, but people are wired differently, so do as thou wilt.

In some ways the reaction to the Netflix adaptation seems to have been yet another thing tainted by our culture wars. The fact that there are LGBT characters and (pardon the phrasing) a black Death, lets self-identified social justice warriors and wokeies signal their virtue by declaring how superlatively awesome it is; while cultural conservatives (and perhaps to a lesser extent the anti-identarian left) can signal theirs by declaring that it’s awful, that Gaiman has ruined his own work with some sort of affirmative action casting of a black woman in a role whose comic book appearance was modeled after a specific white woman and inserting even a bit more gay, lesbian, and queer content, as if it were a woke form of fan service.

So this “not awesome, not awful, it’s okay” review may draw brickbats from both groups…but that’s familiar ground here at TZP.

The Good

The comic version of The Sandman is part of DC comics continuity. The entire concept is a re-imagining of a Golden Age character who wore a gas mask and used a sleeping gas gun to knock out bad guys, more in the tradition of The Shadow or Doc Savage than of Superman or Batman.

The original Wesley Dodds Sandman is retconned by Gaiman’s version. (“Retroactive continuity”, where old facts are put into new context or sometimes just contradicted with “no, it’s always been this way”, is a common tactic of long-running SF franchises.) According to Gaiman’s tale, Dodds was inspired to don his gas mask and put bad guys to sleep by a sort of psychic echo of Morpheus in his helm, during the latter’s captivity.

In the comic book version of the tale, Morpheus encounters Justice League superheroes Scott Free (Mister Miracle) and J’onn J’onzz (The Martian Manhunter) during his quest for his stolen tools, and his ruby is wielded against him by supervillian Doctor Destiny, who has previously tangled with heroes like the Green Lantern.

In that continuity, Hector and Lyta Hall are existing character for whom Gaiman finds new and interesting roles. They are the children of, respectively, Hawkman and Hawkgirl, and Wonder Woman and Steve Trevor…except then the Crisis on Infinite Earths event happened happened and their timeline was destroyed, but they were saved by the power of retcon, but then Hector was killed, but that doesn’t stop superheroes so he became another version of The Sandman in a dream dimension, and…it’s complicated.

Making a clean break from that tangled and sometimes silly DC continuity is probably the right call. (Though I would be interested to see the series work a Wesley Dodds tale into a flashback episode. I don’t think he’s ever appeared in a video adaptation, though I’m sure I’ll be corrected in the comments if so.)

It does mean that we didn’t get to see working-class hero magician John Constantine, with his place in the story replaced by an expanded role for Jenna Coleman as both 18th century adventurer Lady Johanna Constantine and her 21st century descendant of the same name. That has been cause for complaint from some viewers. But while I would have like to have seen John, I will never complain about getting to see the Impossible Girl actress do her thing, and given that John Constantine has appeared in several different film and TV versions already, it was a necessary change to set the series apart.

Also on the matter of casting, this first season includes an adaption of “The Sound of Her Wings”, the comic which first introduced Gaiman’s version of Death. And Kirby Howell-Baptiste plays the hell out of the role. Yes, her face does not look quite like the face that appears in the comics. But every facial expression, every vocal choice, every gesture and element of timing, is spot on, and I look forward to seeing more of her take on the role.

Another spot-on casting choice was Stephen Fry’s Fiddler’s Green. Playing a dream of a place who takes on the guise of a mortal — if eccentric — man, requires an actor to make choices that present the character as grounded but unusual while hinting at unmentioned depths, and Fry nails it.

Even more remarkable is Boyd Holbrook’s Corinthian. The Corinthian’s role in the streaming version is expanded from that in the comics, making him a more significant antagonist for Dream. And Holbrook brings out the most dangerous and frightening aspect of classic serial killers: their charm.

What’s most disturbing about a killer like Ted Bundy or Jeffrey Dahmer isn’t just that they kill — killers, sadly, are a dime a dozen in this world. What’s disturbing is that they get people to trust them, to like them, to even be attracted to them, and then turn on them.

Holbrook’s Corinthian is witty and charming. Gay men and straight women are drawn to him; he charms a young boy into traveling across country with him without question; his fellow serial killers are starstruck by his presence. And Holbrook makes this all believable. You’d buy him a drink or lend him twenty dollars, no questions asked. Or walk around the corner with him into an alley, all unsuspecting…

Tom Sturridge has the right look as Morpheus, but his performance has been criticized as one-note. But this is appropriate for where the character is at this point in the story. Morpheus has only one emotional setting: brooding. So I don’t think we can judge Sturridge’s performance yet.

The Less-Than-Good

The term “fridge logic, popularized by the TVTropes website, refers to plot holes that a viewer caught in the momentum of a story may not notice but become apparent later as that viewer gazes into their refrigerator looking for a beer or a snack. The Netflix Sandman suffers from a gaping plot hole which is not present in the comics, and which viewers might overlook in the coolness of having the protagonist engage in a magical battle with Lucifer, but once spotted it annoys like a sore tooth.

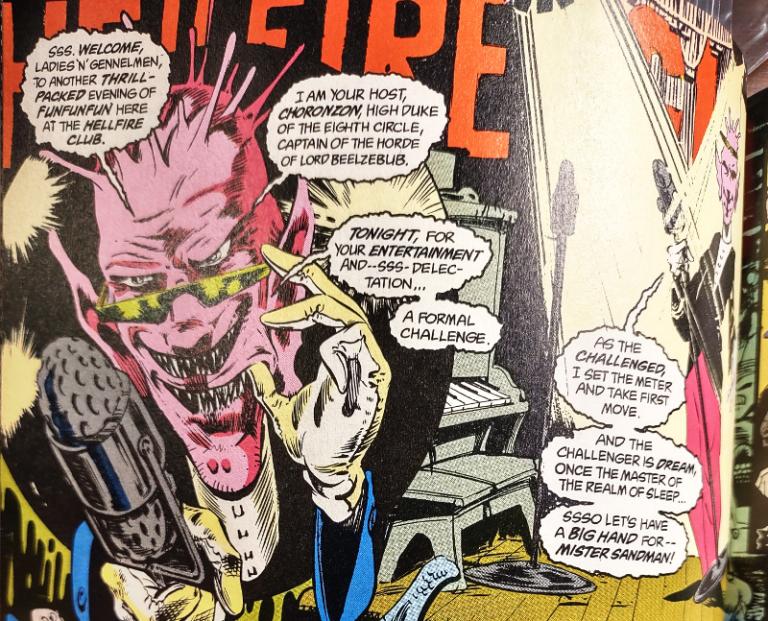

In both versions of the story, Morpheus’s helm is in the possession of the demon Choronzon, a Duke of Hell, a being of some rank and power but not one of the primary powers of the Cosmos. In the comics, it is this demon with whom Morpheus does magical battle via the transformation game, and Morpheus is able to defeat him. It makes sense that, in his de-powered state, Morpheus might find a challenge but ultimately victory in facing this mid-level demon.

The Netflix version, however, has Choronzon pick Lucifer — described by Morpheus himself just moments earlier as possibly the most powerful being in existence save only for “the Creator”, and far more powerful than Morpheus in his current state — as his champion, and take his place in the fight. But Morpheus, weakened by a century of captivity, missing two of the three magical tools into which he has put most his power, is still able to defeat Lucifer on his home turf and on Lucifer’s terms in a fair fight, just because Morpheus has a positive, hopeful attitude? Who then can offer any challenge to him? What obstacle would impede him enough to make a worthwhile story?

Once seen, this just doesn’t work. It’s a disappointing failure of plotting from a master storyteller like Gaiman — especially when he got it right the first time.

Also on the topic of Morpheus’s power level, a change made at the very beginning of the plot doesn’t sit well. In the comics version, Morpheus is vulnerable to the ritual magic of mortals because he is exhausted, having just completed a monumental task on the other side of the Universe. In Gaiman’s words in the introduction to the collected “The Doll’s House” story, “Burgess’s Chant of Summoning had proved the final straw to Someone–Something--already tried almost beyond endurance.” (We are not told what that task was; decades later Gaiman filled in the story in Sandman: Overture.)

But in the streaming version we’re told that Morpheus just happens to be conveniently vulnerable when traveling in the waking world. We’re asked to accept that the King of Dreams is, in a weakened state, powerful enough to defeat Lucifer on Lucifer’s terms in Lucifer’s own living room; yet weak enough, at his full power, to be captured by a not-particularly-impressive mortal magician.

These elements work better and make much more sense in the original comics, and it seems they were changed for no good cause. More attention to continuity would have helped here.

The other problem with the adaption is that it does not seem to trust its audience the way that the comic did.

We can see an example of this in the setup for the aforementioned battle between Morpheus and Lucifer. In the comics, Morpheus’s response of “hope” as the thing which can stand against “anti-life, the Beast of Judgement, the dark at the end of everything” is the sort of moment which makes you put the book down to catch your breath. But the adaption has Nada make a big point of how “I will not give up hope. I will never give up,” and Matthew deliver a homily about “Dreams don’t fucking die,” before that moment.

It’s as if this version doesn’t trust the viewer to appreciate the moment, and so underlines and highlights it to such a degree that it almost tilts into bathos.

Even worse is the end of the adaption of Calliope in the “bonus” episode. In the comics Morpheus is motivated to come to his ex’s rescue largely by his own experience of captivity. He is, at this point, acting more out of an echo of his anger than out of any moral virtue.

But the series doesn’t trust the viewer to understand that it was bad for Erasmus Fry and Richard Madoc to hold Calliope captive and to rape her. We need her to tell us how she now plans to “inspir[e] humanity to want better for themselves and each other”, that she plans to rewrite the laws by which she was held — implying that the magical rules of the series’s universe can easily be changed, in contradiction to all the talk during Morpheus’s visit to Hell about rules and protocols which must be followed.

And then Morpheus — who, let us remember, has had an ex-lover imprisoned in Hell for longer than all of recorded human history and recently declined to forgive and release her — tells us that he will do the same in his realm, use his dream powers to urge humanity onto a “better” course. The series tries to make him into a moral hero at this point in the tale in order to underline the “locking a woman away and raping her is bad” point, but it’s too early, too much in contrast of his decision to continue Nada’s punishment.

I don’t know if this reflects an older Gaiman losing his trust in his audience, or a bit of failure in supervising a group of screenwriters to get them to incorporate such trust into their work.

If in the next season, the writers can trust the audience more and think more deeply about whether changes they make from the comics actually make sense within the series’s universe, then The Sandman could become priory viewing, the sort of show to rewatch over and over.

But for now, while I’m not disappointed in season 1, I’m not enthusiastic about it, and don’t know that I’ll bother to rewatch it.

It’s okay.

Which should be enough; but part of my brain itches and says that the Endless deserve a little more.

* Drooling fanboy moment: I got to see Gaiman in person back when that was a thing you could just do for free during a bookstore tour, rather than needing a high-priced ticket on the lecture circuit. I think it was when American Gods (the novel, not yet the series) was coming out. Even got to talk with him. Me, seeing a favorite author about to walk past me on his way to the autograph table: “Uhhhhhh, hi Neil, thanks for coming out.” Him: “My pleasure.” Return