Mom always said — and quite likely your mom said it too — that two wrongs don’t make a right.

These days, such a thought is considered dangerous, liable to get you accused of “bothsidesing” or “whataboutism”. Whether the two sides in question are the Republicians and Democrats, or Russia and Ukrine, or Israel and Hamas, you are expected to take a side, ignore its sins, and call for the destruction of the other side.

But it is a deep pathology to be unable to say that both sides in a dispute — whether it is a dysfunctional personal relationship, a political rivalry, or a war — are engaged in wrongdoing.

Even if you believe that one of the parties was the original instigator or aggressor, it is vital to be able to see how a long-running cycle of attacks and reprisals degrades the moral character of both sides.

As Buddhaghosa wrote, striking out in anger is like picking up a burning ember or excrement to throw at the enemy: you only burn yourself or make yourself stink.

So imagine the state of two disputants who have been through many cycles of this, burning themselves and covering themselves in shit.

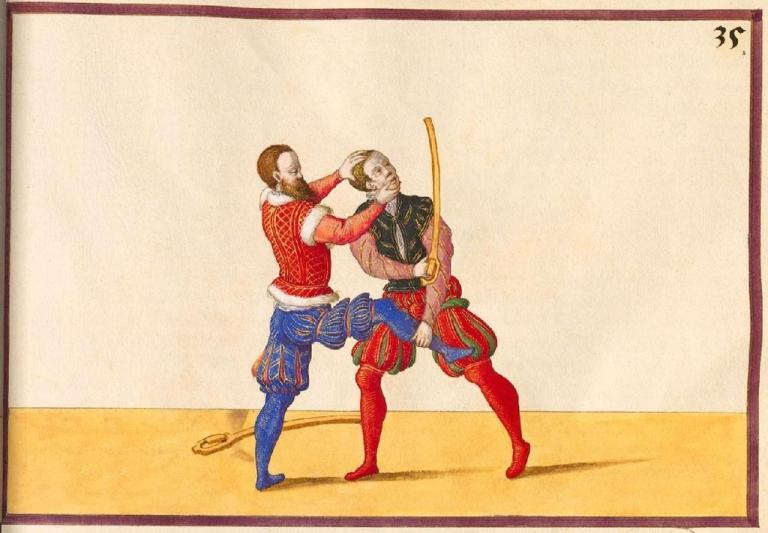

Let us imagine that we walk into a room to find two men fighting, and not in accordance with Marquess of Queensberry rules. Let’s call them Smith and Jones.

As we walk in, Jones trips Smith and kicks him in the ribs while he’s down. In response, when Smith regains his feet he kicks Jones in the groin. In response, Jones seizes Smith’s ear in his teeth and rips it. In response, Smith gouges Jones’s eye.

Because we walked into the room at a point where Jones was attacking Smith with a “dirty” tactic, our sympathies might lie with Smith as a victim of Jones’s attack. But we didn’t see that just a second before that, Smith threw a bottle at Jones’s head. But before that Jones reached for a knife. But before that…and so on.

At this point in a cycle of escalation, it hardly matters who started it.

And a cycle like this can continue until one participant is dead and the other is hideously maimed. So it is in the interests of both sides to stop it.

But in the heat of battle, of anger over the “unfair” tactics used by the other and with a perception (be it true or false) that the other side is an existential threat and cannot be negotiated with, it’s difficult for the combatants to realize this.

The best hope is for a neutral third party, trusted by both sides, to intervene and break things up, interrupting the escalation cycle. But in a highly partisan environment, where remaining neutral is considered a sin, it may be that no such third party may be found.

If no one from the outside is going to save our disputants from each other and from their own darkest impulses, deescalation can only begin with them. And the party who is in the better position to initiate that, is the stronger of the combatants.

In the Israel-Hamas conflict, it’s obvious that Israel is the stronger party — thanks in part to the unconditional backing of the United States. Pointing this out, and suggesting that resolving the conflict has to start with the Israeli/US side, is not a justification of the terror tactics employed by either side. It is a recognition of fundamental realities.

And this is an observation that also applies to our far less consequential personal conflicts. When we are dealing with an annoying coworker, or a problematic family member (especially around the holidays), being willing and able to de-escalate the conflict — to not return a wrong for a wrong — is a sign of strength, not of weakness.