[Note: I am working my way through the process of trying to be approved as a kidney donor for my brother. Part One is here. Part Two is here. Part Three is here.]

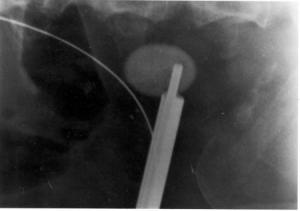

I have now had my last kidney function test–a contrast dye CT scan. Piece of cake.

Afterward, I sat outside on another gorgeous southern California day, watching the people go by. Hordes of what may have been medical school aspirants swarmed past, professional-looking, all in black or gray suits, all young, slender, beautiful, hopeful. Other groups clearly in some sort of educational setting with nametags and carrying big direction cards hurried from one class to another. Patients, patients and more patients many in wheelchairs, most with families, looking hopeful–or despairing–littered the plaza.

The giant, modern medical campus hums with activity, purposefulness, busyness, and nameless untold stories.

I’ve seen a lot of it in my three days here, and yet have seen only perhaps .01% of it. I’m suddenly aware of miles of hidden cables, rivers of plumbing lines, tucked away laboratories, flaming incinerators for hazardous waste, massive underground parking garages–some of the necessary unseens that make a place work.

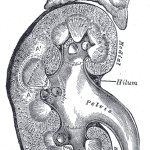

Kind of like the human body. We see so little of it–most hidden, unknown, ignored . . . until something goes wrong. Until a plumbing line backs up or electricity gets shorted out or trash pickup and disposal comes screeching to a halt with a fault somewhere in the system.

When one of those hidden systems goes awry, so goes the whole system. Each part stays dependent upon the full functioning of the rest of the parts. Human bodies, hospitals, governments, churches, denominations, any collective group of any kind functions the same way: it all has to work together and when one part stops, everything else is affected.

Often systems have redundancy built in–alternate pathways so when one part fails, there is a backup that can and will step in. The human body does a pretty good job of that and human resourcefulness does an amazing job helping out where the body alone is inadequate to provide a workaround. The one organ we have that does actually have a built-in redundancy is the kidney. We have a back up–pretty amazing.

This hospital has so perfected the process of kidney donations that they boast a marvelous success rate. But the need just keeps growing. Right now in Southern California, there is an average wait time of seven years for a cadaver kidney after being put on the transplant list. For my brother’s blood type, the wait is closer to 10 years.

I hope that someday there will be implantable artificial kidneys. Right now, dialysis is the only option when in the last stages of renal failure. With the dramatic rise in diabetes both in the US and around the world, the need for transplantable kidneys will be growing exponentially since diabetes tends to damage the kidneys. According to this report, about 30 percent of patients with Type 1 diabetes and 10 to 40 percent of those with Type 2 diabetes eventually will suffer from kidney failure. Scary numbers.

And that’s not the only reason for kidney failure. Most cases have an undetermined cause. That’s the situation with my brother. Nothing to pin it on; nothing to blame. It has just happened.

So, I’m here to see what I can do. This afternoon, I meet with the folks at the transplant nephrology office and then with the transplant surgeon. I go home tomorrow, but without answers, as it will take at least two weeks for a determination to be made. In my case, any potential approval will likely not come immediately–I suspect there will have to be some follow up on minor health issues that are being uncovered here by these thorough exams and tests. They take no chances with potential donors and I appreciate it.

So, I shall write more later as this journey continues.