[This post is a guest post from Alan Duval]

Jonathan has kindly invited me to present my work on the psychology of morality. What follows is largely drawn from my dissertation, which I submitted as part of the requirement for my BSc in psychology. Despite being a psychology dissertation, I did try and bring a lot of philosophy to it, or as much as an enthusiastic amateur in the midst of a psychology degree can. Likewise, due to the limited resources of being a student, getting enough participants in each sub-sample was difficult, so the results here can only be seen as indicative (and hopefully deserving of further research).

It may help, in the first instance, to explain the history of the project. As with many other people that consider themselves liberal, I was interested in, and a little discomfited by Jonathan Haidt’s work on Morality. (If you’re not familiar with Haidt’s work, I’d suggest watching this TED talk[i], or reading his book ‘The Righteous Mind’… It’s fine. I can wait). Liberals, and particularly those that would also call themselves skeptics, do generally seem to be a little more interested in making sure that their beliefs comport with current science, and Haidt, as current science on morality, was disconcerting. I’ve since spoken to a number of people in the atheist/humanist sphere, here in London, and found variations on a theme of discomfort, or a shaky, ideologically-driven disregarding/discrediting of Haidt’s work. The idea that conservatives have five flavours of morality (namely in-group/loyalty, authority, purity (sacredness), harm, and fairness) compared to liberals’ two (harm and fairness) just did not fit with my beliefs about my morality. It did not fit because of my concerns with too many instances of conservative morality being immoral to my way of thinking. (I have tended to call myself a liberal, though leftist or progressive is probably more accurate.) So I set out to find ways to test whether my discomfort was with Haidt’s results and their implications, or if it was purely a matter of ego.

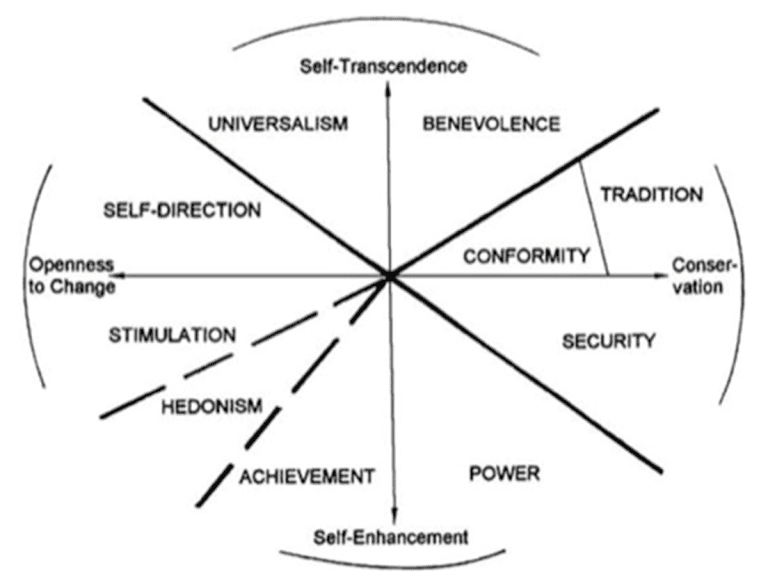

Figure 1: Shalom Schwartz’s (1992) model of values, as presented in Maio, et al. (2014).

Initially I had planned to look at people’s position on an individualist/collectivist scale as well as Bob Altemeyer’s (1981)[ii] RWA scale, as compared to their position on Haidt’s model. RWA stands for Right Wing Authoritarianism, which could be seen as begging the question when trying to debunk what I considered to be a right-leaning scale, but Altemeyer (2006)[iii] is at pains to explain that the scale does find Left Wing Authoritarians, too… if anything this just illustrates the deficiencies of the left/right dichotomy. I say “initially planned…”, because then I met with my supervisor, Ulrike Hahn, and after a bit of discussion she pointed me to her work, with Gregory Maio, using Shalom Schwartz’s (1992[iv]) model of Human Values. This turned out to be important for two reasons:

1) It’s a really good model, that seems to present a complete picture of available human values, from which we individually derive our morality; it has lots of supporting work, generated through years of collecting samples from all over the world, and;

2) It turns out that it was one of the scales that Haidt had used to generate his model (Haidt used a short version of the RWA scale, too).

After reading up on Schwartz, and reading Haidt a little more thoroughly, I came to the conclusion that approximately one quarter of Schwartz’s model was not represented in Haidt’s, and that the quarter that was missing (openness to change) was the quadrant that was most representative of left wing values. If you know Haidt’s work you will be aware that he has added a sixth flavour, Freedom, to include Libertarians. Freedom does appear in the quadrant that I felt that Haidt had excluded (see table). So, with my presumption already partially supported by Haidt’s own work, I set about coming up with a way of confirming my hunch that Haidt’s intention to consciously represent conservative American politics had skewed his model (given that, on many measures, America is an outlier, e.g. Gregory Paul’s (2009) successful societies scale)[v]. The approach I took was to look at the way in which people defined values between Schwartz and Haidt, to see if any of Haidt’s flavours were over-represented, and any of Schwartz’s values were under-represented when comparing the two directly.

| UNIVERSALISM: Wisdom, World of Beauty, World at Peace, Unity with Nature, Social Justice, Protection of the Environment, Broad-Minded, Inner Harmony, Equality | BENEVOLENCE: True Friendship, Mature Love, Responsibility, Meaning in Life, Loyalty, Helpfulness, Honesty, Forgiving, A Spiritual Life | ||||

| SELF-DIRECTION: Choosing Own Goals, Creativity, Curiosity, Independence, Freedom | TRADITION/CONFORMITY: Politeness, Self-Discipline, Honour Parents and Elders, Obedience, Respect for Tradition, Moderate, Humble, Devout, Accepting my Portion in Life, Detachment | ||||

| STIMULATION/HEDONISM: Exciting Life, Varied Life, Pleasure, Daring, Enjoying Life. | SECURITY: Health, Family Security, Social Order, Cleanliness, Reciprocation of Favours, Sense of Belonging, National Security | ||||

| ACHIEVEMENT: Intelligent, Capable, Successful, Ambitious, Influential | POWER: Social Recognition, Wealth, Authority, Preserving Public Image, Social Power | ||||

Table 1: Representation of Shalom Schwartz’s (1992) model of values, including all of the values that make up each of the ten basic values (or goals) in the circumplex model.

It also seemed to make sense to see if there was another reason why liberals rely so much on harm and fairness, where, to conservatives, these are on par with in-group/loyalty, authority, and purity. As part of my reading I had also looked at George Lakoff’s ‘Moral Politics’, which uses his theory of metaphor (Lakoff, 1980)[vi] to describe the differences between liberal and conservative politics. At one point Lakoff (2002, p. 60-61)[vii] details 10 different conceptions of fairness, so I decided to see if the liberal preference for fairness could be explained by a more in-depth understanding of fairness. Whilst my attempt to show a difference with regard to harm, wasn’t well designed, my test for defining fairness worked pretty well.

Haidt’s Flavours vs. Schwartz’s Values

Moral theorizing in psychology, according to Haidt (& Joseph, 2007)[viii], has a Western, Liberal and Secular bias. His response has been to look at morality by focusing on “issues related to binding groups together” (Graham, Haidt & Nosek, 2009, p. 1044)[ix]. In light of this view, Jonathan Haidt (2001[x]; 2007[xi]) and several colleagues (e.g. Graham, Haidt, & Nosek, 2009; Haidt, Graham, & Joseph, 2009[xii]), suggest that the moral domain is made up of five moral ‘flavours,’ which, in combination, divide the population into four key groups. These flavours, when interrogated through Haidt’s Moral Foundations Questionnaire (MFQ), seem to reliably capture distinct views, but none of the five flavours that make up this model express the foremost concern of Libertarians: Liberty. Iyer, Koleva, Graham, Ditto and Haidt (2012)[xiii] sought to ameliorate this by adding Liberty to later versions. But Liberty is an inherently individualistic concern, and as such not about “binding groups together.” By contrast to this, the left side of the Schwartz (1992) model (or at least the left side in the orientation shown above, which to me happens to correspond with the left wing) contains the basic values (goals) of Self-Direction, Stimulation, and Hedonism, all of which relate to evaluations of the importance of things by and for the individual. The inclusion of stimulation as a goal also suggests an underlying need for cognition (e.g. Cacioppo & Petty, 1982[xiv]). Indeed, Iyer, Koleva, Graham, Ditto & Haidt (2012) included Cacioppo and Petty’s ‘Need for Cognition’ scale in their exploration of Libertarian morality and found that Libertarians scored highest, followed very closely by Liberals, with Conservatives bringing up the rear (note that here Libertarian, Liberal, and Conservative are such, as defined by responses to the MFQ, not self-selection).

Sam Harris has had a reasonably public disagreement with Haidt on this and other matters[xv]. Whilst I disagree with Harris on a great number of things, here I think he is on the money. Harris (2011)[xvi] suggests that conservatives may intuitively express harm and fairness through in-group, authority, purity; and indeed Haidt’s work is predicated on his own Social Intuitionist model (Haidt, 2001). As such, Liberals may see elements of harm/fairness within in-group/authority/purity. This could suggest a form of motivated reasoning (see Hahn & Harris, 2014[xvii], for an overview), such as Kahan, et al.’s (2007) “Identity-Protective Cognition” (p. 465[xviii]). In other words; liberals, not being as motivated by stereotypically conservative values, are motivated to find a way to make questions in the MFQ about harm and fairness. This is problematic for the intuitionist as it suggests greater involvement of reasoning. Furthermore, if Harris is correct, liberals would express harm and fairness through such values as stimulation, self-direction, and hedonism (which is both the avoidance of pain as well as the seeking of pleasure), and these do not appear in the MFQ. Indeed, these three values seem to capture liberalism’s core: “freedom of expression and action, and freedom from religious or ideological constraint” (Blackburn, 2008[xix]).

Another issue for Haidt’s intuitionism is that individuals bring two potentially contradictory sets of information to a questionnaire about values, morals, and moral systems. The first is the explicit system to which the individual believes that their personal system belongs; the religious or political affiliation with which they identify. The second is the implicit system, which is how they actually respond to moral questions, whether captured by the MFQ, or other questions. There is a third response-set, not addressed here: how an individual actually behaves in a morally salient situation. Bob Altemeyer (2006), in his work on Authoritarianism, points out that behaviour, and not a score on a test, shows how one actually is. Graham, et al. (2011, p. 17, note 3[xx]) make the same distinctions. This is odd, as intuitionism relies on the difference between explicit and implicit, and whether or not an individual is correct that their implicit (intuition-led) beliefs accord with their explicit (stated) belief structure. Simply comparing participants’ claimed political and religious beliefs with their results from the MFQ illustrates this.

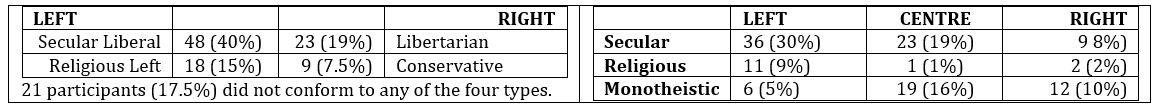

Table 2: Participants’ results as defined by the Moral Foundations Questionnaire, left, and simple demographic self-selection.

According to the MFQ my sample was 40% Secular Liberal, 19% Libertarian, 15% Religious Left, and 7.5% Conservative, with 17.5% ‘Other’ (presumably some of whom are either fiscally or socially conservative, but not both). By simple self-selected Religio-Political Orientation my sample was 30-49% Secular Liberal, 8-30% Libertarian, 14-31% Religious Left, and 12-29% Conservative. There’s not a whole lot of agreement going on there, a wide range in those headings, and Libertarians are disproportionately represented. It should be noted that Haidt and colleagues state that the MFQ is not diagnostic. Just as well, really.

So, ignoring political or religious orientations, how did people define the segments of Schwartz’s model using Haidt’s moral flavours? If comparing values with morals strikes you as not exactly apples with apples, consider the definition of values that motivates Schwartz’s model: Values are (1) beliefs about (2) goals or behaviours, that are (3) trans-situational, and (4) evaluative of individuals, acts, and occurrences that (5) stand in relation to each other and thereby (6) establish an implicit moral system (Schwartz, 1992; Schwartz & Bilsky, 1987[xxi]; 1990[xxii]). What this implies is that any given moral should have one value that is more strongly associated with it than others, and this should bring out the difference between implicit and explicit beliefs. Furthermore, this should get to the intrinsic, intuition-led morals of an individual, rather than their explicit system (assuming there is any difference between these), and this should favour Haidt’s intuitionism.

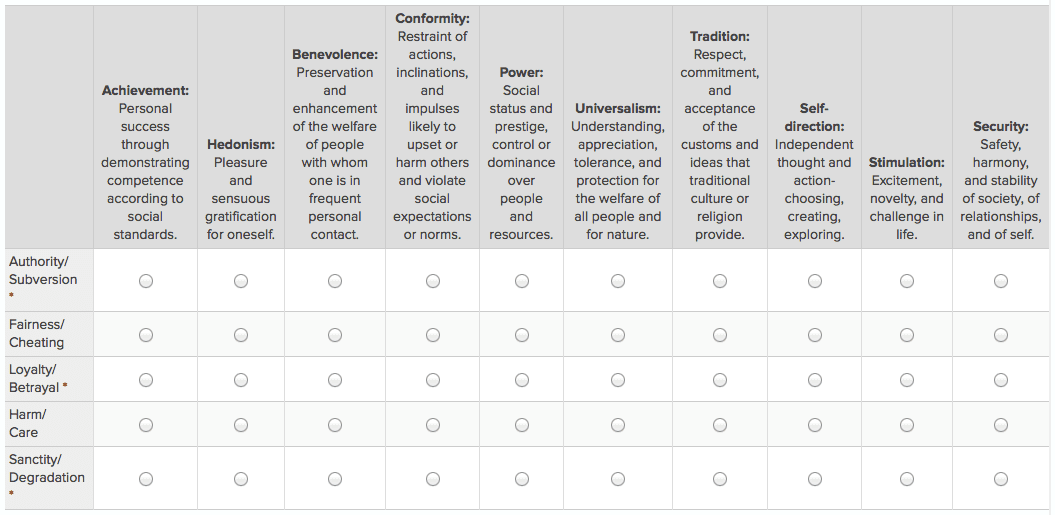

Table 3: So, which of the values along the top is the most important for describing the moral concern on the left?

It turns out that more than 40% of all participants agreed that harm/care was best exemplified by self-transcendence (benevolence or universalism); authority/subversion by self-enhancement (achievement or power); and both loyalty and sanctity by conservation (security, conformity, and tradition). Notice that openness (self-direction, stimulation, hedonism) is not even in the game, coming last or second-to-last in defining all of Haidt’s flavours. Not only this, but openness was behind conservation in every single value. It seems likely that the inclusion of ‘freedom’ would change this picture. Of the two flavours that featured highest under openness, fairness is one (supporting my hypothesis), but curiously purity (sanctity/degradation) is the other. If pushed, I would suggest that this has more to do with the degradation aspect (with reference to hedonism) than the sanctity aspect.

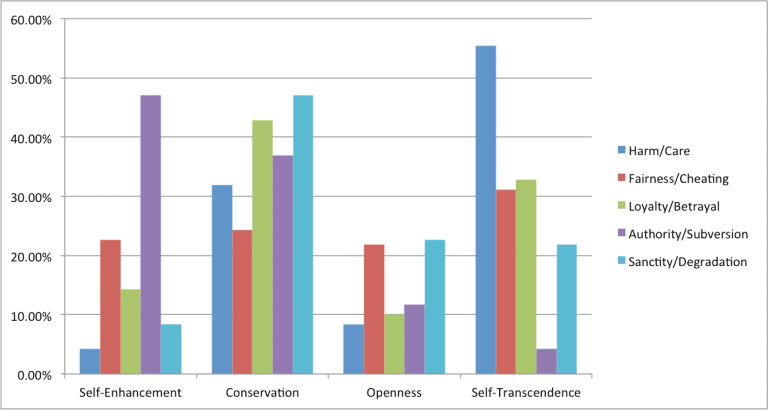

Figure 2: Percentage of each moral flavour, as represented by each value quadrant (compiled from individual responses at the value level). Which value quadrant is therefore best represented by the MFQ, and which the least?

So, I seem to have established that none of Haidt’s flavours represent openness. Or, if you prefer, none of the values represented by openness are dominant components of harm-care, fairness-cheating, loyalty-betrayal, authority-subversion, or sanctity-degradation (aka purity). Further, it seems that fairness is in some way a meta-value, appearing approximately equally in all four values, which supports Sam Harris’ contention, though these results suggest that conservatives also agree to some extent, that fairness is a means by which all values are expressed, which would be contrary to Harris’ view. Fairness was most strongly represented in self-transcendence. This makes sense, as that seems to be the meeting place for secular and religious liberals (which is as far as Haidt goes in representing the left), and explains why the left relies on it. To clarify, under the heading of self-transcendence are the values of benevolence (a more religiously oriented value), and universalism (a more secular value). To illustrate how benevolence is religious and universalism secular, consider the difference between the Golden Rule (central to much religious thought, and ignoring individual difference), and Karl Popper’s Platinum Rule (1966, p. 386), “The golden rule is a good standard which can perhaps even be improved by doing unto others, wherever possible, as they would be done by.” Consider also Rawls’s (1971)[xxiii] ‘Original Position’ wherein one would apply rules to society before knowing what place one inhabits within that society. In both cases we are employing an individual’s understanding of other people’s likely preferences to define right action, rather than expecting them to conform to some more general (social, group-binding) standard.

On this matter of fairness, then: if it is approximately equally represented by all of Schwartz’s values, and of key importance to liberals under Haidt’s conception of moral flavours (and his conception of liberals), how do liberal, conservative, secular and religious individuals discuss fairness?

To look at this, as mentioned, I used the 10 types of fairness put forth by Lakoff (2002, p. 60-61) in his book, Moral Politics:

1) Equality of Distribution (e.g. one child, one cookie)

2) Equality of Opportunity (e.g. one person, one raffle ticket)

3) Procedural Distribution (e.g. playing by the rules determines what you get)

4) Rights-based Fairness (e.g. you get what you have a right to)

5) Need-based Fairness (e.g. the more you need, the more you have a right to)

6) Scalar Distribution (e.g. the more you work, the more you get)

7) Contractual Distribution (e.g. you get what you agree to)

8) Equal Distribution of Responsibility (e.g. we share the burden equally)

9) Scalar Distribution of Responsibility (e.g. the greater your abilities, the greater your responsibilities)

10) Equal Distribution of Power (e.g. one person, one vote)

As expected under my hypothesis, both the left-leaning and the secular participants relied on more ways of conceptualizing fairness to decide whether something is moral (eight and nine, respectively), than the centrists, moderates, and the religious (between four and six).

There were three conceptions of fairness that were common to all political persuasions (though not necessarily to the same degree):

1) Equality of distribution

8) Equal distribution of responsibility

10) Equal distribution of power

Furthermore, both leftists and centrists agreed that ‘Contractual Distribution’ was important. The right did not. The left and the right agreed on ‘Rights-based fairness’, centrists did not.

There were three conceptions of fairness that were common to all religious persuasions (again, not necessarily to the same degree):

3) Procedural distribution

7) Contractual distribution

8) Equal distribution of responsibility

The religious (but not monotheistic) considered ‘scalar distribution of responsibility’ to be important, here the secularists agreed with the monotheists. They also agreed on ‘equality of distribution’, ‘equality of opportunity’, and ‘equal distribution of power,’ the non-monotheistically religious did not.

At this point I am departing from my original work and theorizing based on the results, and my own subsequent thinking on the matter.

Implications

If these fairnesses are part of a meta-value (or motivation) of fairness, then maybe we can apply them to the types of discourse they relate to. To my way of thinking politics is exemplified by the Schwartz values of power and security, and politics brought out ‘equal distribution of power’, and ‘equality of distribution’ as definitional conceptions of fairness. This seems to imply that a primary issue for security is equality of distribution (the previously mentioned ‘Successful Societies Scale’ by Gregory Paul would tend to support this). So if that’s political fairness, what of religious fairness?

Schwartz (2012)[xxiv] noted that Spirituality was originally tested as a universal value, but failed to achieve consistency across cultures, and in the samples where it did show up, the underlying values were split between Benevolence and Tradition (Schwartz, 1994[xxv]). These are social-oriented values, not individual-oriented. Nelson (2009)[xxvi] notes that Spirituality is generally used to denote the personal side of transcendent experience. However, Spirituality and Religion are often used interchangeably – though there are movements based on a distinction, e.g. ‘spiritual, but not religious’ (Fuller, 2001[xxvii]; Gallup, 2003[xxviii]) – it may be that religion is spirituality in light of society, and is expressed in light of or through benevolence and tradition (Saroglou, Delpierre & Dernelle, 2004[xxix]). I suggest that religion has done a good job of co-opting the term ‘spiritual’. Whilst religion may be a path to spiritual experience for people, it is primarily about the “binding together of groups”. It should be noted that Schwartz does not agree with me on this distinction (personal correspondence, 2015).

It is interesting that the fairnesses that relate to religious views (including secular) were contractual and procedural distribution. Respectively, “you get what you agree to” and “playing by the rules determines what you get.” Or, in more overtly Christian language, ‘accept God/Jesus/The Holy Spirit into your life and you’ll go to heaven, don’t and you’ll go to hell,’ and ‘be good and you’ll go to heaven, don’t and you’ll go to hell.’ These seem to be more related to the value of conformity and tradition than benevolence, they also seem to imply a social contract, which suggests an underlying (and unstated) politics.

As the reason for looking at fairness was to establish why liberals place fairness in high regard, to the exclusion of in-group/authority/purity, it is interesting to note that the left, generally, agreed on the importance of all conceptions of fairness but for ‘equality of opportunity’ and ‘contractual distribution’, where the secular agreed on all conceptions of fairness but ‘scalar distribution of responsibility’. ‘Equal distribution of responsibility’ was agreed upon as important by all sub-samples, regardless of political or religious orientation, so we can maybe put that to one side as a central or unifying conception of fairness.

What all this seems to mean is that the values either not represented or under-represented by Haidt – stimulation, hedonism, and achievement, universalism and self-direction – may have the remaining types of fairness associated with them.

I take stimulation, hedonism, and achievement to be both the private aspect of religion (aka spirituality, self-discovery, etc.) and, as outlined elsewhere, definitional of both liberals in particular, and the left more generally. On the other hand, universalism and self-direction, I would group under the heading of self-governance (for want of a better term), and these are also values held to by the left, in general, but also by at least some self-professed progressives, and anarchists, and libertarians.

So can these be seen to relate to ‘equality of opportunity’, ‘rights-based fairness’, ‘need-based fairness’, ‘scalar distribution’, and ‘scalar distribution of responsibility’ (the fairnesses that weren’t agreed upon by religion and politics)? Or is there some other relationship? For example, Scalar Distribution (e.g. the more you work, the more you get) is in direct conflict with Scalar Distribution of Responsibility (e.g. the greater your abilities, the greater your responsibilities) – which seems very much like the libertarian ‘taxes are theft’ argument explained as an issue of conflicting conceptions of fairness. This seems to relate to achievement, as scalar distribution, in opposition to benevolence, as scalar distribution of responsibility.

If we can assign these two forms of scalar distribution in this way, then there remains ‘equality of opportunity’, ‘rights-based fairness’, and ‘need-based fairness’ to be matched up to self-direction, stimulation, and hedonism, or maybe there are still more conceptions of fairness to be considered, and other ways of relating them to values. At a rough guess, I would anticipate that self-direction seems a natural match to ‘equality of opportunity’ in that if we all have access to things, we can choose which things have meaning and value to us. Stimulation, then, matches up with ‘need-based fairness’, because it is through stimulation that one becomes aware of needs (the feelings of hunger and thirst, and so forth). Finally, and purely by a process of elimination, hedonism would therefore be attached to ‘rights-based fairness’. An attempt to harmonise this might be that rights are predicated, at least in part, on needs, and hedonism is predicated on the pleasantness or unpleasantness of stimulation.

This is already a long piece, so I’ll wrap up by saying that I have created an updated version of Schwartz’s model that reflects the above, and more. If there is interest, I will be happy to do a follow-up that introduces and discusses that. At the very least I will explain why I stopped using the term hedonism, from Schwartz’s model, and discuss what I have put in its place.

RELATED POSTS

- Duval vs Haidt: A Very Brief History of Moral Psychology; Critiquing Haidt

- The Internal Logic of Human Morality – Duval’s Model of Moral Psychology

NOTES

[i] Jonathan Haidt’s TED talk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vs41JrnGaxc

[ii] Altemeyer, B. (1981). Right-Wing Authoritarianism. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

[iii] Altemeyer, B. (2006). The Authoritarians. Winnipeg: Lulu.com Available here: http://members.shaw.ca/jeanaltemeyer/drbob/TheAuthoritarians.pdf

[iv] Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25(1), 1265. Available here: http://kodu.ut.ee/~cect/teoreetiline%20seminar%2023.04.2013/Schwartz%201992.pdf

[v] Paul, G. (2009). The chronic dependence of popular religiosity upon dysfunctional psychosociological conditions. Evolutionary Psychology, 7(3), 147470490900700305. Available here: http://evp.sagepub.com/content/7/3/147470490900700305.full.pdf

[vi] Lakoff, G. Johnson, M. (1980). The metaphorical structure of the human conceptual system. Cognitive Science, 4(2), 195-208. Available here: http://www.fflch.usp.br/df/opessoa/Lakoff-Johnson-Metaphorical-Structure.pdf

[vii] Lakoff, G. (2002). Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think (2nd Ed.). London: University of Chicago Press. Relevant section viewable here: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=MTKR3o2PICMC pg=PA386 dq=moral+politics hl=en sa=X redir_esc=y#v=onepage q=Scalar%20Distribution%20of%20Responsibility f=false

[viii] Haidt, J., Joseph, C. (2007). The moral mind: How five sets of innate intuitions guide the development of many culture-specific virtues, and perhaps even modules. In P. Carruthers, S. Laurence, and S. Stich (Eds.) The Innate Mind, Vol. 3, 367-392. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Available here: http://evolution.binghamton.edu/evos/wp-content/uploads/2009/08/Haidt2.pdf

[ix] Graham, J., Haidt, J., Nosek, B. A. (2009). Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 10292 1046. Available here: http://www-bcf.usc.edu/~jessegra/papers/GrahamHaidtNosek.2009.Moral%20foundations%20of%20liberals%20and%20conservatives.JPSP.pdf

[x] Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: a social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108(4), 814-834. Available here: https://www.motherjones.com/files/emotional_dog_and_rational_tail.pdf

[xi] Haidt, J. (2007). The new synthesis in moral psychology. Science, 316(5827), 998-1002. Available here: http://www.unl.edu/rhames/courses/current/readings/new-synthesis-haidt.pdf

[xii] Haidt, J., Graham, J., Joseph, C. (2009). Above and below left–right: Ideological narratives and moral foundations. Psychological Inquiry, 20(223), 110-119. Available here: http://faculty.virginia.edu/haidtlab/articles/haidt.graham.2009.above-and-below-left-right.pub070.pdf

[xiii] Iyer, R., Koleva, S., Graham, J., Ditto, P., Haidt, J. (2012). Understanding libertarian morality: The psychological dispositions of self-identified libertarians. PLOS One, 7(8), e42366. Available here: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0042366

[xiv] Cacioppo, J. T. Petty, R. E. (1982). The need for cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1), 116-131. Available here: http://psychology.uchicago.edu/people/faculty/cacioppo/jtcreprints/cp82c.pdf

[xv] https://evolution-institute.org/article/why-sam-harris-is-unlikely-to-change-his-mind10/

[xvi] Harris, S. (2011). The Moral Landscape: How Science can Determine Human Values. New York: Simon and Schuster. Relevant section viewable here: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5FRW30QaDQwC printsec=frontcover dq=The+Moral+Landscape hl=en sa=X redir_esc=y#v=onepage q=Haidt f=false

[xvii] Hahn, U. Harris, A. J. (2014). What does it mean to be biased: Motivated reasoning and rationality. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 41, 41-102. Available here: http://www.ucl.ac.uk/lagnado-lab/publications/harris/Hahn_Harris_L M2014.pdf

[xviii] Kahan, D. M., Braman, D., Gastil, J., Slovic, P. Mertz, C. K. (2007). Culture and identity-protective cognition: Explaining the white-male effect in risk perception. Journal of Empirical Legal Studies, 4(3), 465-505. Available here: http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1100 context=fss_papers

[xix] Blackburn, S. (2008). Liberalism, In The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy (2nd Ed., revised). Oxford: Oxford University Press, p.209.

[xx] Graham, J., Nosek, B. A., Haidt, J., Iyer, R., Koleva, S. & Ditto, P. H. (2011). Mapping the moral domain. Journal of personality and social psychology, 101(2), 366. Available here: https://webfiles.uci.edu/phditto/peterditto/Publications/Graham%20et%20al%20JPSP%202011%20copy.pdf?uniq=-5wjp2s

[xxi] Schwartz, S. H., & Bilsky, W. (1987). Toward a universal psychological structure of human values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 550-562.

[xxii] Schwartz, S. H., & Bilsky, W. (1990). Toward a theory of the universal content and structure of values: Extensions and cross-cultural replications. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 878-891.

[xxiii] Rawls, J. (1971) A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[xxiv] Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.9707/230720919.1116 Also available here: http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1116&context=orpc

[xxv] Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and contents of human values? Journal of Social Issues, 50(4), 19-45. Available here: http://www.the-brights.net/morality/statement_3_studies/Schwartz,%20S.%20H.%20(1994).%20Are%20there%20universal%20aspects%20in%20the%20structure%20and%20contents%20of%20human%20values_%20Journal%20of%20Social%20Issues,%2050(4),%2019-45.pdf

[xxvi] Nelson, J. M. (2009). Psychology, Religion, and Spirituality. New York: Springer Science + Business Media, LLC. DOI: 10.1007/97820238728757326_1

[xxvii] Fuller, R. C. (2001). Spiritual, but not religious: Understanding unchurched America. Oxford University Press.

[xxviii] Gallup, G. H. (2003). Americans’ Spiritual Searches Turn Inward. In Gallup: Religions and Social Trends. Retrieved April 14, 2016, from http://www.gallup.com/poll/7759/americans2spiritual2searches2turn2inward.aspx

[xxix] Saroglou, V., Delpierre, V. & Dernelle, R. (2004). Values and religiosity: A meta-analysis of studies using Schwartz’s model. Personality and Individual Differences, 37(4), 721-734. Partially available here: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228911242_Values_and_Religiosity_A_Meta-Analysis_of_Studies_Using_Schwartz’s_Model