I am going to explain to you why species do not exist and in some sense there is no such thing as speciation in evolutionary biology. This will involve philosophy, sand dunes, voting, colours and fossils. Amongst other things.

The Sorites Paradox

My favourite philosophical thought experiment, if you can call it that, and as many of my readers might know of me, is the Sorites Paradox. It can be defined as follows:

The sorites paradox[1] (sometimes known as the paradox of the heap) is a paradox that arises from vaguepredicates.[2] A typical formulation involves a heap of sand, from which grains are individually removed. Under the assumption that removing a single grain does not turn a heap into a non-heap, the paradox is to consider what happens when the process is repeated enough times: is a single remaining grain still a heap? If not, when did it change from a heap to a non-heap?[3]

The paradox arises in this way:

The word “sorites” derives from the Greek word for heap.[4] The paradox is so named because of its original characterization, attributed to Eubulides of Miletus.[5] The paradox goes as follows: consider a heap of sand from which grains are individually removed. One might construct the argument, using premises, as follows:[3]

- 1000000 grains of sand is a heap of sand (Premise 1)

- A heap of sand minus one grain is still a heap. (Premise 2)

Repeated applications of Premise 2 (each time starting with one fewer grain) eventually forces one to accept the conclusion that a heap may be composed of just one grain of sand.[6]). Read (1995) observes that “the argument is itself a heap, or sorites, of steps of modus ponens“:[7]

- 1000000 grains is a heap.

- If 1000000 grains is a heap then 999999 grains is a heap.

- So 999999 grains is a heap.

- If 999999 grains is a heap then 999998 grains is a heap.

- So 999998 grains is a heap.

- If …

- … So 1 grain is a heap.

This is crucial for my larger point.

What creationists claim

Creationists very often demand silly things like evidence that dogs give birth to non-dogs. Indeed, in a recent thread, a creationist stated these indicative remarks:

Lots of redheads coming out of Ireland isn’t evolution. Redheads coming (eventually) out of “Rhubarb”, now THAT’s evolution.

and

You’re the one who’s confused. Evolutionists claim “evolution” happens right before our eyes when bacteria “evolve” *RESISTANCE* to antibiotics. (I say NO evolution. The antibiotic-susceptible bacteria and the antibiotic- resistant bacteria are …

BOTH BACTERIA, one is no less a bacteria than the other.)But the same scientists demur, I guess for political correctness, that the mutation that causes some human beings to have *RESISTANCE* to malaria (via the sickle cell mutation) is NOT evolution. You know, because they do NOT want to say those blacks with sickle-cell are NOT humans anymore. (And they’re right to not say that, but they’re right for the wrong reason.)

and

Well, if scientists think that evolution does *not* mean new species AND evolution does *not* mean common ancestry, then I guess I believe in evolution.

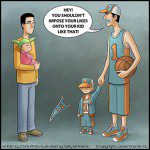

What you should be able to see here is that such a position demands of evolution clear speciation and particular points. A dog must give birth to a non-dog.

The problem is, this doesn’t happen and evolutionary scientists will be the first people to tell you this. If you are demanding this of evolution, and never get it, it is no wonder you deny evolution because it is nothing but a shoddy straw man of properly defined evolution.

Categorising stuff

We love to use categories. That’s a blue flower, that’s a red car, that’s an adult, that’s a child. It’s how we navigate reality in a practical sense – it provides our conceptual map. However, you shouldn’t confse the map with the terrain. Essentially (good word choice), we make up labels to represent a number of different properties. A cat has these properties, a dog these. Red has these properties, blue these. Often we agree on this labelling, but sometimes we don’t. What constitutes a hero? A chair? Is a tree stump a chair?

The problem occurs when we move between categories. It is at these times that we realise the simplicity of the categories shows weakness in the system.

You reach eighteen years of age. You are able to vote. You are now classed as an adult. You are allowed to buy alcoholic drinks (in the UK). But there is barely any discernible difference in you, as a person, physically and mentally, from 17 years, 364 days, 11 hours, 59 minutes, 59 seconds, and you 1 second later.

However, we decide to define that second change at midnight as differentiating the two yous and seeing you move from child (adolescent) to adult. These categories are arbitrary in where we exactly draw the line. Some countries choose sixteen, some younger, some older. These are conceptual constructs that allow us to navigate about a continuum of time. You can look at a five-year-old and the same person at twenty-eight and clearly see a difference. But that five-year-old and the same person one second later? There is no discernible difference.

And yet it is pragmatically useful for us to categorise, otherwise things like underage sex and drinking would take place with wild abandon, perhaps. Sixteen for the age of consent is, though, rather arbitrary. Why not five seconds later? Four days? Three and a half years?

Speciation is exactly the same. There is no real time where a population of organisms actually transforms into a new species. Because species is a human conceptual construct that does not exist objectively. We name things homo sapiens sapiens but cannot define exactly where speciation occurred. In one sense, it does not occur. In another, if you look at vastly different places on the continuum, it does (at least in our minds).

This is a version of the Sorites Paradox.

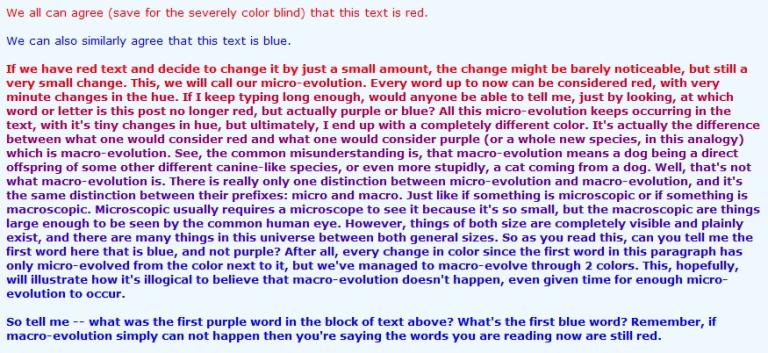

As I have shared several times, this image sums it up with aplomb:

Examples with recent human ancestry

We know this happens very clearly because there have been skulls found that have aspects and properties of what we think one (sub)species has, and other properties of another species. It is not different enough from either to be a new species, and thus it really is truly transitional. As all fossils are. The whole continuum of any branch is transitional right the way along. There are no category markers. As Dawkins states in The Greatest Show on Earth (but without images – it’s a long quote, but nails it):

Now for my next important point about allegedly missing links and the arbitrariness of names. Obviously, when Mrs Ples’s name was changed from Plesianthropus to Australopithecus, nothing changed in the real world at all. Presumably nobody would be tempted to think anything else. But consider a similar case where a fossil is re-examined and moved, for anatomical reasons, from one genus to another. Or where its generic status is disputed – and this very frequently happens – by rival anthropologists. It is, after all, essential to the logic of evolution that there must have existed individuals sitting exactly on the borderline between two genera, say Australopithecus and Homo. It is easy to look at Mrs Ples and a modern Homo sapiens skull and say, yes, there is no doubt these two skulls belong in different genera. If we assume, as almost every anthropologist today accepts, that all members of the genus Homo are descended from ancestors belonging to the genus we call Australopithecus, it necessarily follows that, somewhere along the chain of descent from one species to the other, there must have been at least one individual who sat exactly on the borderline. This is an important point, so let me stay with it a little longer.

Bearing in mind the shape of Mrs Ples’s skull as a representative of Australopithecus africanus 2.6 million years ago, have a look at the top skull opposite, called KNM ER 1813. Then look at the one underneath it, called KNM ER 1470. Both are dated at approximately 1.9 million years ago, and both are placed by most authorities in the genus Homo. Today, 1813 is classified as Homo habilis, but it wasn’t always. Until recently, 1470 was too, but there is now a move afoot to reclassify it as Homo rudolfensis. Once again, see how fickle and transitory our names are. But no matter: both have an apparently agreed foothold in the genus Homo. The obvious difference from Mrs Ples and her kind is that she had a more forward-protruding face and a smaller brain-case. In both respects, 1813 and 1470 seem more human, Mrs Ples more ‘ape-like’.

Now look at the skull below, called ‘Twiggy’. Twiggy is also normally classified nowadays as Homo habilis. But her forward-pointing muzzle has more of a suggestion of Mrs Ples about it than of 1470 or 1813. You will perhaps not be surprised to be told that Twiggy has been placed by some anthropologists in the genus Australopithecus and by other anthropologists in Homo. In fact, each of these three fossils has been, at various times, classified as Homo habilis and as Australopithecus habilis. As I have already noted, some authorities at some times have given 1470 a different specific name, changing habilis to rudolfensis. And, to cap it all, the specific name rudolfensis has been fastened to both generic names, Australopithecus and Homo. In summary, these three fossils have been variously called, by different authorities at different times, the following range of names:

KNM ER 1813: Australopithecus habilis, Homo habilis

KNM ER 1470: Australopithecus habilis, Homo habilis, Australopithecus rudolfensis, Homo rudolfensis

OH 24 (‘Twiggy’): Australopithecus habilis, Homo habilis

Should such a confusion of names shake our confidence in evolutionary science? Quite the contrary. It is exactly what we should expect, given that these creatures are all evolutionary intermediates, links that were formerly missing but are missing no longer. We should be positively worried if there were no intermediates so close to borderlines as to be difficult to classify. Indeed, on the evolutionary view, the conferring of discrete names should actually become impossible if only the fossil record were more complete. In one way, it is fortunate that fossils are so rare. If we had a continuous and unbroken fossil record, the granting of distinct names to species and genera would become impossible, or at least very problematical. It is a fair conclusion that the predominant source of discord among palaeoanthropologists – whether such and such a fossil belongs in this species/genus or that – is deeply and interestingly futile.

Hold in your head the hypothetical notion that we might, by some fluke, have been blessed with a continuous fossil record of all evolutionary change, with no links missing at all. Now look at the four Latin names that have been applied to 1470. On the face of it, the change from habilis to rudolfensis would seem to be a smaller change than the one from Australopithecus to Homo. Two species within a genus are more like each other than two genera. Aren’t they? Isn’t that the whole basis for the distinction between the genus level (say Homo or Pan as alternative genera of African apes) and the species level (say troglodytes or paniscus within the chimpanzees) in the hierarchy of classification? Well, yes, that is right when we are classifying modern animals, which can be thought of as the tips of the twigs on the evolutionary tree, with their antecedents on the inside of the tree’s crown all comfortably dead and out of the way. Naturally, those twigs that join each other further back (further into the interior of the tree’s crown) will tend to be less alike than those whose junction (more recent common ancestor) is nearer the tips. The system works, as long as we don’t try to classify the dead antecedents. But as soon as we include our hypothetically complete fossil record, all the neat separations break down. Discrete names become, as a general rule, impossible to apply. [Chapter 7]

In philosophy, there is a position called (conceptual) nominalism, which is set against (Platonic) realism. This conceptual nominalism, as I adhere to, denies in some (or all) cases the existence of abstracts. These categories we invent don’t exist (a word that itself needs clear defining), at least not outside of our heads. Thus species do not exist as objective categories. We invent them, but if all people who knew about species suddenly died and information about them was lost, then so too would be lost the concept and categorisation.

When we look at two very different parts of a continuum we find it easy to say those things are different and are of different categories, but when we look in finer detail, this falls apart. There is a fuzzy logic at play.

Species do not exist. Well, they do in our heads. When we agree about them. And only then so we can nicely label pictures in books, or in our heads.

Some quotes

Wikipedia has some nice quotes on the subject. Follow the links for sources and references:

“No term is more difficult to define than “species,” and on no point are zoologists more divided than as to what should be understood by this word.” Nicholson (1872, p. 20).[54]

“Of late, the futility of attempts to find a universally valid criterion for distinguishing species has come to be fairly generally, if reluctantly, recognized” Dobzhansky (1937, p. 310).[13]

“The concept of a species is a concession to our linguistic habits and neurological mechanisms” Haldane (1956).[46]

“The species problem is the long-standing failure of biologists to agree on how we should identify species and how we should define the word ‘species’.” Hey (2001).[49]

“First, the species problem is not primarily an empirical one, but it is rather fraught with philosophical questions that require — but cannot be settled by — empirical evidence.” Pigliucci (2003).[17]

“An important aspect of any species definition whether in neontology or palaeontology is that any statement that particular individuals (or fragmentary specimens) belong to a certain species is an hypothesis (not a fact)” Bonde (1977).[55]

![By Felipe Schenone (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://wp-media.patheos.com/blogs/sites/617/2016/11/causality.jpg)