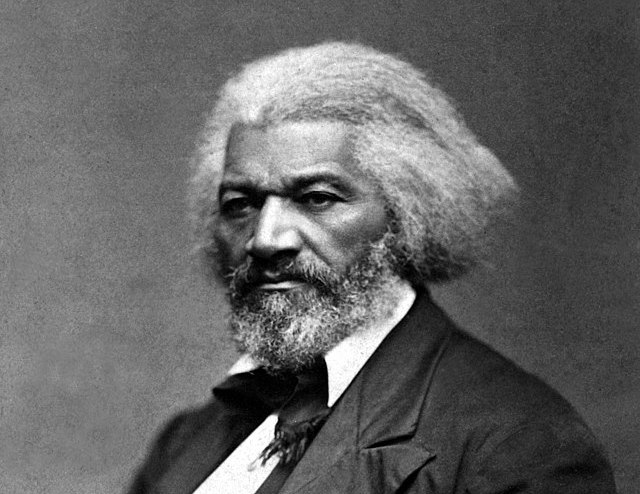

In his famous speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?” Frederick Douglass reflects on how the peals of church bells and cries of jubilation commemorating this great nation’s birthday lands on the ears of the two Americas. The two Americas, of course, are White America and Black America. The riches of justice and freedom that this day commemorates are the inheritance of White Americans, not Black Americans. “The sunlight that brought life and healing to you,” Douglass argues, “has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

In characteristic fashion, Douglass’ rhetorical brilliance flashes through the speech. He lauds the courage and genius of the Founding Fathers and the great promise of the young nation. At the same time, he condemns the bloodstain of slavery that cries from the ground and corrupts the hearts and the minds of her people. Douglass traces America’s awful scars that mark the distance between her ideals and her reality. He defies the audience to search the globe so see if any nation, any despot can match the “revolting barbarity and shameless hypocrisy” of America.

If he pulls no punches when talking about the nation, the gloves come off when he address the American Church. And rightly so: America has not lived up its manmade charter but the Church has defied divine command to love your neighbor as yourself. “The Church of this country,” Douglass contends, “is not only indifferent to the wrongs of the slave, it actually takes sides with the oppressor…the American Church is guilty, when viewed in connection with what it is doing to uphold slavery; but it is superlatively guilty when viewed in connection with its ability to abolish slavery.”

And yet, for all this, Douglass is a prophet of hope. He holds on to the hope that the young America is still in its infancy and may mature yet into a nation that lives into its ideals. His hope is that the fire rained down in the speech might quicken the conscience of the nation.

As we commemorate another Fourth of July nearly 170 years later, it is important to reflect on the state of the nation. How much has changed since Douglass addressed the crowd on July 5, 1852? Did Douglass hope in vain? As an American and a pastor, I think this is a live question for the American Church. Has she been compromised?

If you replace the word “slavery” with “racism” and “slave” for “person of color” in Douglass’ indictment above, you would have a fine summary of the argument Jemar Tisby persuasively makes in his book The Color of Compromise. Tisby chronicles the American Church’s complicity in racism. From the colonial era to the Civil War, from Reconstruction to Jim Crow, from the Civil Rights movement to mass incarceration, the (White) American Church has been complicit in the nation’s original sin of racism. Chattel slavery has been abolished, racism has not.

There is no doubt – we have inherited a sordid history. But as the preacher will tell you: we may be products of our past but we need not be prisoner to it. Or, as Douglass puts it, “We do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future.”

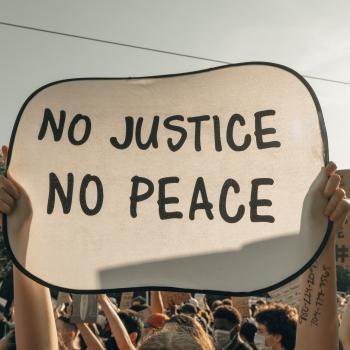

Hope is the belief that tomorrow can be better than today. Over the past year we have glimpsed glimmers of a better tomorrow: in the number and magnitude of racial justice protests, in guilty verdicts for coldblooded murder, in making Juneteenth a federal holiday. At the same time, we witnessed insurrection of the Capitol and the full-court press to restrict voting in nearly every state.

Racial justice has not arrived. The struggle continues. Change is slow and incremental and messy. The work of truth-telling and confession, of repentance and reconciliation, of reform and repair is massive. After centuries of damage, the work of reconciliation will be an exercise in hope.

This July 4th offers all Americans the opportunity to reflect on the promise of this great nation. As churches across the nation gather for worship, this Sunday offers American Christians the opportunity to reflect on the possibility that America is in the midst of another great awakening, one in which the church finally lives into its prophetic witness. White Christians have been inexcusably late to the protest, but hopefully not too late. “Now is the time, the important time,” as Douglass says, to align with, support, contribute to churches who take every opportunity to put their hand to the plow in this hard work.