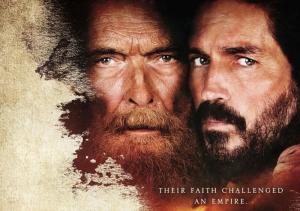

We in the West must constantly seek out reminders of what real hardship looks like. Last week I was given a screener for “Paul, Apostle of Christ,” starring Jim Caviezel, who played Jesus in “The Passion of the Christ,” as well as James Faulkner from “Downton Abbey.” This biblical movie was just such a reminder, not only of what it’s like to endure persecution for the name of Christ, but of the fact that the Apostles and early Christians were real people who didn’t know they would become living legends–or even that anyone would remember their stories.

The film, directed by Andrew Hyatt, takes place during Paul’s second imprisonment in Rome, after his appearance before Emperor Nero ends in a death sentence. The least of the Apostles (Faulkner) is locked in the deepest dungeon in Rome, under the charge of a suspicious and ruthless prefect (Olivier Martinez), and seems to believe his part in the Church’s story is over. That’s when Luke (Caviezel) shows up to encourage his old friend and to write down his story. Having recently finished his gospel, the Greek physician believes the Christian world needs to know and remember the man who brought it the Good News. He wants to pen a sequel to the book of Luke, which will follow the life and ministry of Paul–we know that book, of course, as Acts.

The film, directed by Andrew Hyatt, takes place during Paul’s second imprisonment in Rome, after his appearance before Emperor Nero ends in a death sentence. The least of the Apostles (Faulkner) is locked in the deepest dungeon in Rome, under the charge of a suspicious and ruthless prefect (Olivier Martinez), and seems to believe his part in the Church’s story is over. That’s when Luke (Caviezel) shows up to encourage his old friend and to write down his story. Having recently finished his gospel, the Greek physician believes the Christian world needs to know and remember the man who brought it the Good News. He wants to pen a sequel to the book of Luke, which will follow the life and ministry of Paul–we know that book, of course, as Acts.

But much stands in Luke’s way. Paul’s time on earth is slipping away like sand in an hour glass, and his Roman captors are none-too-eager to allow Luke to smuggle his notes out of the Apostle’s cell.

In the meantime, the Christian church in Rome is facing intensified persecution after Nero blames them for the great fire and begins filing them into the Colosseum and onto crosses. This isn’t “Storykeepers.” Members of the underground church led by Aquila and Priscilla have to face a tide of bodies that wash up every night in the storm of Caesar’s wrath. Some (especially the young men) begin to lose heart, and decide to fight back. In one poignant scene, the community mourns the loss of a young boy who was beaten to death by soldiers, and one of the hotheads shouts, “This is what trusting in God gets you!” He soon leaves behind the other Christians and takes up the sword. The elders must make the hard decision to either stay in Rome under the shadow of the arena, or flee without a clear idea of where to go.

Even Paul appears to have lost heart, and takes some convincing of the value in Luke’s writing project. He eventually comes around, and even regains his sense of humor, in spite of fresh floggings and a stream of heartbreaking news. Paul also finds closure in relating his journey from Saul of Tarsus, that “Hebrew of Hebrews” and zealous oppressor of the Church, to missionary to the Gentile world. He comes to realize that although he still feels worthy of great suffering for the name of the God he once persecuted, his story is the story of all blind sinners, captured by amazing grace and allowed to see.

Paul and Luke also find a means of winning the prefect’s respect and gratitude, and are allowed to finish their project before Paul’s execution. They don’t quite make a believer out of the hard-hearted Roman, but they do surprise him with a dramatic display of Christ’s command to “do good to those who hate you.” The movie closes with Paul’s march to the chopping block as we hear the words of his second letter to Timothy, which he slips into Luke’s hand for delivery:

“For I am already being poured out like a drink offering, and the time for my departure is near. I have fought the good fight, I have finished the race, I have kept the faith. Now there is in store for me the crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous Judge, will award to me on that day—and not only to me, but also to all who have longed for his appearing.”

Whatever your eschatology, “Paul, Apostle of Christ” undeniably portrays Nero’s persecution as a kind of tribulation. Despite the modest run time, this film creates a sense of crushing weariness, and even hopelessness. It prompted me to candidly admit to my wife, “I have no idea whether I would be able to profess Christ if you and our children were threatened like this.” A character remarks that most of the Roman Christians had never met or talked with Jesus. It is remarkable that they are still willing to die for Him, as they believe He died for them.

This is one of the better biblical movies in recent years. It stands head-and-shoulders above some of the cringe-worthy gimmicks in the History Channel’s “Bible” miniseries, and is more respectful to the source material by miles than Darren Aronofsky’s “Noah” or Ridley Scott’s “Exodus: Gods and Kings.” One gets the sense that Caviezel (already well-established in the genre) and Faulkner really believe the lines they’re reciting, many of which come verbatim from the epistles.

It’s far from perfect, though. Much of the script is weighed down by pacifist pulpit-pounding. Characters like Aquila, Priscilla, and even (at times) Paul make Christianity out as a distinctly feminine call to political nonviolence, more than a masculine call to earthly justice and fealty to a King who claims global sovereignty.

One of the few non-biblical mantras Faulkner repeats epitomizes this doormat theology: “Love is the only way”–as if love can never take up arms in defense of the weak, in resistance against a tyrannical government, or even to make good an escape. In one apocryphal scene, Paul refuses to leave his prison cell after a band of renegade Christians shows up to spring him. He says something reminiscent of Romans 13 and sends his rescuers on their way. One wonders how those who barely escaped the Islamic State in recent years would feel about this. One wonders how the real Apostle Paul, who only ever refused escape to save a jailer’s soul, would feel about it.

The script writers also made the irritating choice to translate the Greek “Ekklesia” as “community,” rather than the more traditional “church,” which gave much of the dialogue a distinctly “spiritual-but-not-religious” vibe.

At its worst moments, “Paul, Apostle of Christ” is a preachy, pacifist parable. At its best, it is biblical film-making come into maturity, and a window for Western eyes into what persecution looks like. It’s saturated with Pauline and Lukan quotations that point past the blood and sweat of worldly hardship to the heavenly prize that awaits all who trust in Christ. I found myself tearing up as Caviezel’s Luke tells a group of frightened children who hear the roaring of the beasts in the Colosseum that it will be painful, but only for a moment. Then, he says, they will see Jesus.

The best part of the film is the last ten minutes. Paul tells the prefect in charge of his execution that he isn’t interested in trying to reason him into Christian faith. It is Christ, not a human evangelist, who shatters unbelievers’ resistance. Paul knows this better than most. To this, the puzzled prefect asks how the Apostle can so calmly go to his end for such a testimony. Paul explains that this life is like a handful of water that slips through our fingers whether we want it to or not. Eternity is like the water in the ocean. Most people live for the vanishing puddle over which Rome has control, by God’s leave. Christians live for the ocean. It’s how they can have a peace that passes understanding, and the courage to see life as Christ’s and death as gain.

Image: Affirm Films