By Hakeem Muhammad and Khalid Sharif

“Even God turned his back on us ghetto youth, I know that ain’t the truth, sometimes I look for proof.” — Tupac Shakur

Theodicy is the most foundational question of theology, attempting to come to terms with how evil and suffering exists in a world full of divine goodness. Black suffering in America takes the form of insidious violence, seemingly without end. The particularity of this inquiry is often overlooked within contemporary Islamic discourses that have been disconnected from the realities of Black Americans.

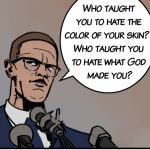

Hip-Hop has historically provided an avenue for disenfranchised black youth to speak to their lived realities, posing theological questions that Muslims should address. Though music is often frowned upon within Muslim settings, it is with no apology that we analyze Tupac’s lyrics. His words articulated the realities of street life that Muslims must come to terms with.

Segments of the black population continue to subsist in the most wretched of conditions in ghettoes: poverty is ubiquitous, early deaths are normalized, and violence is unending, as a disproportionate amount of the inhabitants of these ghettoes are systematically routed into the ever-growing prison industrial complex. The sheer horrors of ghetto life lead to many feelings sentiments of abandonment by God—if God is ar-Raheem (the most merciful), where is this mercy to black folks in the ghetto? Tupac is left in search of this proof and ponders, “I wonder if the lord still cares for us [Black folks] on welfare.”

Tupac was not merely speaking of his own subjective reality, his life embodied the conditions of the inner city youth. Through his work, he not only highlighted the social conditions, mentalities, and activities of the ghetto, but also key theological inquiries posed by many of its inhabitants. To answer this question, we shall examine the works of Al Jahiz, a Black Islamic philosopher of the 9th century who lived in the Abbasid Caliphate.

The belief that God turned his back on ghetto youth is predicated upon an assumption that Al-Jahiz brilliantly summarizes: “If there were design in this world one would expect that the righteous would thrive and the wicked be deprived; the strong would be prevented from oppressing the weak.” Following this line of thinking, the mayhem and struggles that characterize life in the ghetto, would not exist if there were in fact a merciful Creator. In an answer to this, Al-Jahiz states, “If this were the case there would be no place for the trails of life by which people distinguish themselves.”

From Al Jahiz’s perspective, the unparalleled oppression facing black folks provides the opportunity to distinguish themselves within their societies and ultimately to God; the trials and struggles placed in their lives allows blacks to inculcate tenacity, determination, and perseverance. It is within these very trials and struggles that facilitated noble individuals such as Tupac Shakur, to distinguish himself as brave leader for social justice.

While Tupac discusses the plight of blacks who are often born without a silver spoon, Al- Jahiz challenges the notion that being born in luxury is superior to be born in poverty, indicating that excess affluence, comfort, and privilege have the detrimental impact of spiritual lethargy, becoming spoiled, and the development of adverse characteristic traits that are displeasing to God. In a world devoid of suffering, Al-Jahiz indicates that the human being would “sink to the status of beasts ruled by the stick and the carrot alternately, to make them behave.”

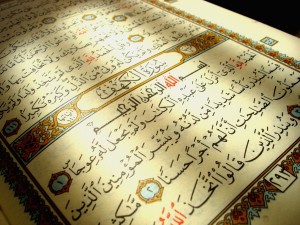

In contrast to working hard to obtain God’s pleasure, Al-Jahiz states that the human would no longer “make the effort to do good and righteous deeds, seeking and trusting in God’s promised reward.” Thus, the “Problem of Suffering”, is actually no problem at all, it only becomes a problem based upon a liberal anthropocentric worldview in which human beings are entitled to pleasure and that the only reason God would exist is to maintain human creation in a blissful state of pleasure. Such a worldview is counter to Islam, in which when God loves a people; God puts trials and difficulties upon them: the greater the difficulty, the more potential award one can gain in the akhira.

Yet, Al-Jahiz would be sure to point out, the fact that God permits there to be suffering does not mean that humans do not have obligations to rectify social conditions that resulted in suffering. Tupac Shakur advocates just this in “Panther Power”, indicating the imperative to spark change within society arguing that black folks “Couldn’t survive in this capitalistic government because it was meant to hold us back.” Highlighting the immediacy of black suffering, Tupac Shakur states, “It’s time to change the government now.” Al-Jahiz whose analysis of the problem of evil centered upon the Akhira (hereafter) would remind Tupac Shakur that punishment that God can inflict upon a people for refusing to struggle for justice is infinitely greater than the repressive violence a worldly state can commit.

Similarly, the rewards that God is capable of granting to those who strive in his cause is infinitely greater than the temporal comforts that can be offered from capitulating to a repressive state. This iman, or faith in God, can become a powerful tool for Black freedom struggle leaving the confines of the pessimism that undergirds the material world to a spiritual hope in the hereafter. Far from advocating complicity with the evil in this world, Islam provides the means of renewing faith and provides a mechanism to escape the nihilism of an anti-black world.

In an answer to Tupac’s original question, Al-Jahiz would answer the very suffering that exists in the black community is in fact a proof that God has not turned his back on the ghetto youth and God most certainly cares about black folks on welfare. The trials and obstacles that blacks endure in America provides a path towards divine distinction, overcoming life’s obstacles through Sabr (patience),- a trait that can be manifested in facing adversity. In the Qur’anic worldview human beings are created for a purpose, to face obstacles and struggles and achieve a higher goal to earn God’s favor.

The ultimate reward of this striving will manifest in the hereafter, which according to Al-Jahiz,”comes to those who have worked for it and deserved it.” Al-Jahiz would be in agreement with Tupac Shakur when he states,” Then it make sense that God would put us in the ghetto, That means he wants us to work hard to get up out of here. That means he’s testing us even more.” Yet, the fact that God permits there to be suffering does not mean that human beings do not have the obligation to challenge unjust social structures that lead to suffering, thus Al-Jahiz in smooth Arabic prose would tell Tupac that black folks in the hood should keep striving, demonstrating perseverance and tenacity as they work to change the condition of their community and earn the pleasure of God. But in black colloquial English, Al-Jahiz would tell ‘Pac, “Keep grindin’, homie.”

The Next Hip-Hop Halaqa:

Ronald Reagan often cited Islamic economist Ibn Khaldun to justify his economic policies. It was the very policies that are often critiqued within Hip-Hop as contributing to the further marginalization of Black communities. In the Next Hip-Hop Halaqa, we will conduct a thought experiment: what would Ibn Khaldun actually have to say to hip-hop artists, Killer Mike , about the devastating impact that Reaganomics had on the black community?