Someone recently told me that “Diplomacy always fails; military confrontation alone is able to solve problems.” While the current crisis involving ISIS requires military intervention, efforts in diplomacy must never cease. While I cannot imagine governments negotiating with ISIS, I also cannot imagine a situation where diplomacy is abandoned.

Someone recently told me that “Diplomacy always fails; military confrontation alone is able to solve problems.” While the current crisis involving ISIS requires military intervention, efforts in diplomacy must never cease. While I cannot imagine governments negotiating with ISIS, I also cannot imagine a situation where diplomacy is abandoned.

Governments must make sure that they do not disenfranchise and relationally disengage minority populations and religious groups. Afzal Amin, a former British military leader who is a Muslim, claims that British society shares some blame in the emergence of the “jihad generation.” A recent Independent article paraphrases Amin claiming that “young Muslims in inner-city Britain have been left disenfranchised by politics and let down by imams and other community leaders.” While this rationale does not seem to address all cases of Western-raised Muslims joining forces with ISIS (an article and video about the Glasgow girl turned bedroom radical and ISIS bride suggests that it could happen to anyone), it does account for many instances.

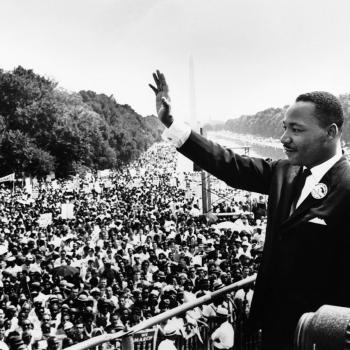

Perhaps Amin’s words about Britain bear relevance for the United States, too. The news that British and American young people have sympathies and allegiances with groups like ISIS is quite troubling. To the extent that such connections are fueled by disillusionment and distress over a lack of opportunity to flourish as honorable members of democratic and capitalistic societies, to that extent (and more) these same societies must become intentional about inspiring hope that involves deconstructing exclusive structures and fostering widespread ownership.

The Independent article addresses the need for Muslim leaders to connect better with youths to make sure they are well-adapted in their Western cultural contexts. It is also important for Christian leaders like myself to make sure we treat Muslims in the West with respect as equals and cultivate relationships with them as neighbors and friends. All of us have a role to play in proactive diplomacy before, during, and after military conflicts occur. After all, no military confrontation can solve the problem of hate. No one can force us to love others and seek reconciliation; only God’s love in Christ in the power of the Spirit can compel Christians to love others from the heart (See Romans 5:5; 2 Corinthians 5:14-15), including a “jihad generation.”

My Muslim friends tell me the primary meaning of jihad is the internal struggle within oneself to battle and overcome evil. I need to take a look inside myself and ask what I am doing to overcome insular ways that exclude others and be a good neighbor to those who are different from me. All of us who are Christians must do the same. After all, the Lord Jesus said we must first take out the plank from our own eyes before removing the speck from others’ eyes. (Matthew 7:5). With this in mind, perhaps we are all to blame for the “jihad generation” in one way or another. Whether or not we think we might bear some measure of blame, how many of us are willing to move beyond pursuing this generation to the gates of hell, as Vice-President Biden’s words about ISIS itself might compel us to do? How might we open up our hearts to these disillusioned and deeply confused youths and provide them with opportunities to succeed as honorable members of our societies? This type of diplomacy could very well be the way for inner city Muslim youths to stay put and “Glasgow girls” to return home.