The canonical gospels present Jesus’ complex and troubling relationship with Jerusalem. Take for example Matthew 23. Matthew 23 presents Jesus longing to gather its people to himself: “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it! How often would I have gathered your children together as a hen gathers her brood under her wings, and you were not willing!” (Matthew 23:37; ESV). It should be noted that Jesus’ cry of longing follows his outcry against the religious hierarchy for their hypocrisy and injustice (See Matthew 23:1-36). Within a few chapters, we find Jesus dead on a cross outside Jerusalem’s city gates (See Matthew 27).

John’s Gospel also takes issue with key elements of the religious and political hierarchy, not the Jewish people themselves. We find in John 10:31-42 that members of the Jewish establishment seek his death whereas the people flock to him in the wilderness (John 10:31-42). This contrast serves as a strong condemnation of the power structure in place during Jesus’ day.

John’s Gospel presents those who broker power doing anything to preserve their position and the nation as a whole (See Jn 11:48). By the way, the same is true of Pilate who is willing to hand over Jesus unjustly once his own position of power is under threat in the face of the claim that Pilate opposes Caesar if he takes Jesus’ side against his accusers (John 19:12-16). The tragic irony is that, from Jesus’ perspective, the Jewish authorities’ attempt to bring about their preservation and salvation will actually bring about Jerusalem’s ruin.

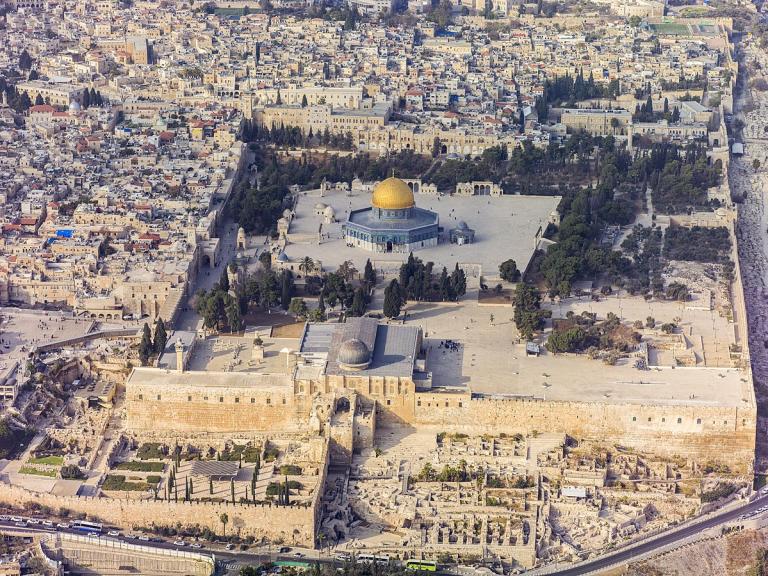

N.T. Wright claims that Jesus’ unique interpretation of the tradition gives rise to the religious establishment’s rejection of him. The Pharisees maintain that Jesus’ take on the tradition will bring about their and the nation’s demise at the hands of Rome. To the contrary, it is Jesus’ framework that alone would preserve and secure their destiny.[1] For example, the Galilean Jesus’ cleansing of the temple in Jerusalem and offering of forgiveness of sins apart from worship and performance of sacrifices at the temple de-center the power structures and reframe opposition to the political establishment.[2] Jesus becomes the point of reference, not a building or city. Jesus’ body is the ultimate temple, as we find Jesus suggesting in John 2. Jesus makes this claim in the context of cleansing the temple and the authorities’ demand for an authoritative basis for his actions:

So the Jews said to him, “What sign do you show us for doing these things?” Jesus answered them, “Destroy this temple, and in three days I will raise it up.” The Jews then said, “It has taken forty-six years to build this temple, and will you raise it up in three days?” But he was speaking about the temple of his body. When therefore he was raised from the dead, his disciples remembered that he had said this, and they believed the Scripture and the word that Jesus had spoken (John 2:18-22; ESV).

Like John the Baptist, Jesus’ ministry is populist in nature. Like John, Jesus operates largely outside the centers of power. Whereas the Hebrew Scriptures locate so much of the prophetic activity inside Jerusalem, as with Nathan, Ezra and Nehemiah, for example, we find the religious establishment sending representatives to John the Baptist out in the countryside to discern whether he is the Christ, Elijah, or the prophet (John 1:19-28). Moreover, such populism is not limited to Jewish people. Followers or believers in Jesus include Samaritans (See John 4), Greeks (See John 12:20-23), and other Gentiles (See for example Matthew 27:54). Jesus is the lamb who takes away the sin of the whole world (John 1:29).

In John 10, we find opposition to Jesus taking place around the Feast of Dedication in Jerusalem (John 10:22-24). This particular feast honors the second temple’s re-dedication at the time of the Maccabean Revolt in the face of pagan rule in the second century B.C. So much of the tension and opposition recorded in John’s Gospel takes place in Jerusalem around feasts such as this one, including the Passover and Feast of Tabernacles. The confrontation centers on Jesus’ identity.

In light of the preceding discussion, it leaves one to ponder the biblical basis for many Evangelical Zionists’ fixation with Jerusalem. Might not their unflinching support for the opening of the U.S. embassy in Jerusalem with its supposed apocalyptic import actually bring about Jerusalem’s demise, or at least unfathomable distress, like a self-fulfilling prophecy based on their interpretation of Scripture that the nations will rise up against Jerusalem and Israel in the end times? For all their talk of Jesus, would it not make more sense biblically and prudently to focus on Jesus, not Jerusalem? After all, Jesus centered the discussion on himself, not Jerusalem. It is worth pointing out that the Israel government does not embrace Jesus but tolerates Evangelical Zionism for political and nationalistic purposes (to many American Jews’ chagrin). Ironically, in Jesus’ day, such nationalism paved the way along with the Pax Romana to Jesus’ crucifixion. Moreover, one can hardly imagine Jesus going in with the political and religious establishment today in paving the way for his own kingdom, when the Sanhedrin, Pilate and Herod all opposed him. Lastly, Jesus, the ultimate populist, always identifies with those outside the centers of power, Jews and non-Jews alike, including Palestinians, many of whom have embraced him as their Savior and Lord throughout the centuries to the present day. Those Evangelical Zionists who fixate on Jerusalem threaten not only the ultimate peace process, but also witness to Jesus among the very diverse peoples he came to save.

_______________

[1]See N.T. Wright, The Challenge of Jesus: Rediscovering Who Jesus Was and Is (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 1999), pages 57-58.

[2]See also Wright’s entire chapter “The Challenge of the Symbols,” in The Challenge of Jesus, pages 54-73.