Conspiracy theories come in all sizes and shapes and fall across the ideological and cultural spectrum. A conspiracy theory may be true or false, even though we typically assume “conspiracy theories” are just plain false (Refer here to an article detailing “5 US national security-related conspiracy theories that turned out to be true”).

Now, no one I know or have come across wants to be called a conspiracy theorist, as it is generally considered a derogatory label. It can be like calling someone a cult leader or member. So, when we use both terms to label someone, we are in danger of insulting them twice.

To clear up misconceptions about conspiracy theories and their immediately negative associations and reactions, it will prove beneficial to provide a working definition. Here’s how political scientist Joseph E. Uscinski, an expert on the subject matter, defines conspiracy theories in a recent video recorded interview:

A conspiracy theory…is a[n] accusatory perception in which a small group of powerful people are working in secret for their own benefit against the common good and in a way that undermines our bedrock ground rules against the widespread use of force and fraud. And further, this perception has not been granted legitimacy as true by the appropriate epistemological experts with data that is open to refutation.

Based on this definition, New Testament Christianity may have been deemed a conspiracy theory movement. It was also considered a sect or cult—fringe group. We will return to this topic in a future post.

Now, let’s categorize a few different kinds of conspiracy theories. We might find a divine conspiracy theory, as in Dallas Willard’s book The Divine Conspiracy, which is on Jesus’ school of discipleship. We might come across a demonic conspiracy theory, as in C.S. Lewis’s Screwtape Letters in which the demons prey on a human. Lastly, we might read about a human conspiracy theory, as in Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s All the President’s Men, which was the full account of the Watergate Scandal.

What would count as other examples of human conspiracy theories? Depending on how one defines “epistemological experts,” as articulated above in Prof. Uscinski’s definition, “human” conspiracy theories may include the following examples: the movie JFK, Whitewater, the documentaries Inconvenient Truth, Inconvenient Sequel, and Bowling at Columbine, Benghazi, Pizzagate, and Russian Collusion (Check out the interview with Prof. Uscinski on the nature and breadth of conspiracy theories, including in the political realm, and how to analyze their presumed merits).

For what it’s worth, I affirm some of these “conspiracies theories” as more sound/true than others. Still, based on Prof. Uscinski’s definition and depending on how one defines “epistemological experts,” they might all fit the label “conspiracy theory.” Now one might think (wrongly) that I am conspiring to infuriate ‘both sides’ by claiming that conspiracies theories are no respecter of the right or left. Rather than dismiss out of hand a claim marshaled against one’s preferred political party, candidate, religion (for example, The DaVinci Code), and personal icon with the label “conspiracy theory,” we need to consider each conspiracy theory claim and discern whether it is factual.

In view of the prior reflections, what is required is public scrutiny, subject matter expertise, patience, and civility. No doubt, the process of evaluation and engagement of a given conspiracy theory can be exacting and exhausting. However, that does not excuse us from doing the heavy lifting and analyzing each claim as to its potential merits. Here are some (though not all) helpful guidelines to consider when analyzing conspiracies theories and their critiques:

- Those making the conspiracy theory claims must themselves go public rather than remain anonymous to enhance the credibility of their assertions. One of my concerns about Q of QAnon is that we do not know who Q is. Given the gravity of Q’s allegations, it is important to come forward and announce him or herself as well as substantiate the claims made.

- Those making the conspiracy theory claims must be open to vetting and debating their theories with subject matter experts. Vague allusions easily come across as delusions. While subject matter experts themselves may be found to be in error during or as a result of the discourse, all parties must be willing to analyze and debate theories thoroughly. It is important that those who put forth theories that detail conspiracies guard against making unsubstantiated claims, ones that they easily retract later without admitting mistakes. A claim that is not open to falsification cannot be substantiated and verified, and thus cannot be regarded as truly meaningful. The onus is on those putting forth conspiracy theories, or what are deemed conspiracies against the prevailing expert opinion in a given field, to make the case for their assertions and allegations, as the burden of proof is on them. A charge in itself does not warrant acceptance.

- Those articulating what are considered conspiracy theories or who are seeking to dismantle them appear more trustworthy when they do not serve to benefit or profit from their assertions, but perhaps have everything to lose. Consider here the FBI’s rigorous attempts to discredit Martin Luther King, Jr. under Edgar J. Hoover. According to The Washington Post,

Until her own death in 2006, Coretta Scott King, who endured the FBI’s campaign to discredit her husband, was open in her belief that a conspiracy led to the assassination. Her family filed a civil suit in 1999 to force more information into the public eye, and a Memphis jury ruled that the local, state and federal governments were liable for King’s death. The full transcript of the trial remains posted on the King Center’s website.

Dr. King and his family certainly suffered greatly for what they took to be the FBI’s withering and unjust scrutiny (Note here: sometimes those who seek to expose conspiracy theories as untrue may themselves be in danger of losing everything, as a Scientist American article points out in the case of scientist Stephan Lewandowsky). While not surefire proof, since someone asserting a conspiracy theory may wish to go down in history as unique or as a sacrificial lamb with a martyr’s complex, nonetheless, willingness to risk all for one’s claims merits that their views receive closer analysis.

From the flipside, consider here the statement Sara Northrup, former wife of L. Ron Hubbard, the Founder of Scientology, alleged that Hubbard made. Business Insider writes,

If true, that’s a staggering, disturbing claim, since religion does not exist to make people wealthy, but relationally whole. Now whether one would consider Scientology’s claims over the years that false information was being circulated worldwide to discredit Hubbard and the church a conspiracy theory, the Los Angeles Times claimed that Scientology’s operation “Snow White” evolved into a “massive criminal conspiracy.” Here is the full context of the statement in the Los Angeles Times:

Snow White began in 1973 as an effort by Scientology through Freedom of Information proceedings to purge government files of what Hubbard thought was false information being circulated worldwide to discredit him and the church. But the operation soon mushroomed into a massive criminal conspiracy, executed by the church’s legal and investigative arm, the Guardian Office.

Related to the point above on making conspiracy claims or assertions that do not prove self-serving, those confirming the accuracy of conspiracy theories add to their credibility to the extent their organization or movement is at risk of losing ground as a result of the charges. For example, Republicans and Democrats, Atheists and Christians, enhance the merits of their claims when they side with positions that could damage their political and ideological parties. Such was the case back in 1974 when an increasing number of Republicans in Congress refused to protect President Nixon in 1974 from the specter of impeachment.

- Another important factor comes into play when analyzing conspiracy theories. We gain credibility when we do not shout down our opponents, resort to character assassinations and name calling like “stupid,” “crazy,” “despicable,” and “disgusting.” We gain a greater hearing across the cultural divide in addressing conspiracy theory claims when we are peaceable, humble, and where possible empathic. For more on this subject, check out Chris Anderson’s interview with Bill Gates on TED starting at 30:37, especially beginning at 33:30. Anderson’s problematic language, quoted above, flies in the face of what Jonathan Haidt shared with Anderson about what is needed in public discourse at TedTalks in 2016: “Can a Divided America Heal?”

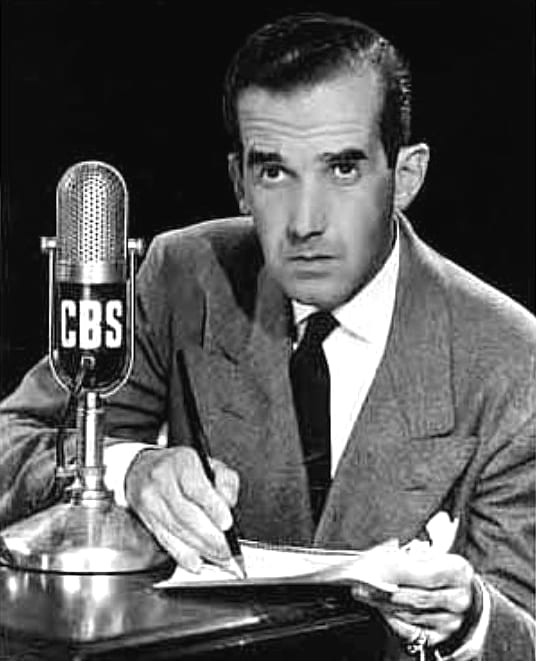

Whether we are asserting a conspiracy theory or trying to dismantle one, we could learn a thing or two from the renowned broadcast journalist Edward R. Murrow who took on the powerful US Senator Joseph McCarthy who destroyed people and their careers as he sought to rid the US government and society of what McCarthy alleged was widespread communist infiltration (Refer here for Murrow’s March 1954 broadcast critiquing McCarthy’s “Red Scare” claims and tactics). In an age where sensationalism easily dominates politics, religion, and the news, we can all learn from and follow the example of Murrow, who was known for his “just-the-facts, no-hype style of reporting and his careful separation of opinion from facts.” “The ultimate argument against McCarthy wasn’t Murrow’s facts, but his character.”

In the next post on this subject, we will consider whether the Christian faith and its claims function as a conspiracy theory.

Check out this video discussion for more on the subject matter of this blog post.

https://youtu.be/7ekQh_32uhY