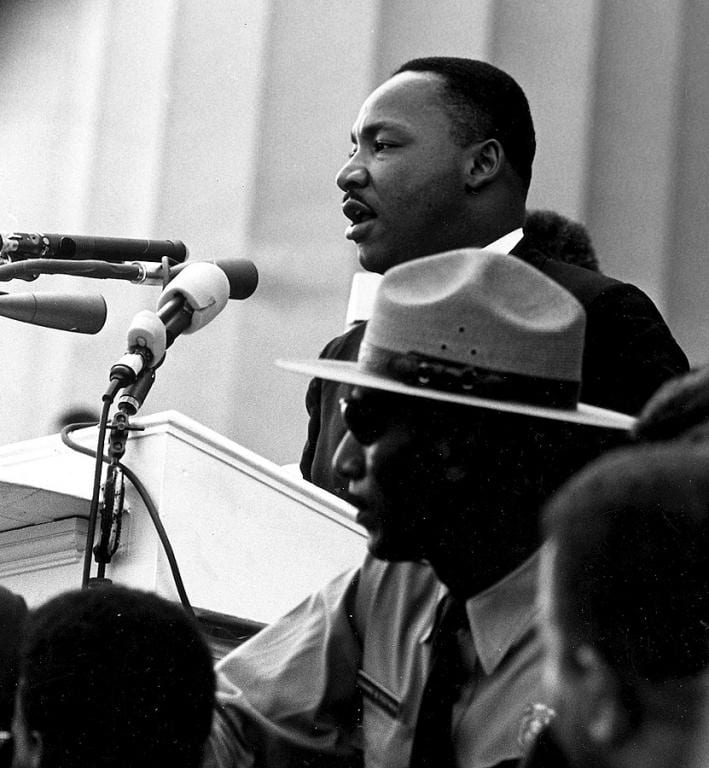

Federal holidays are intended to highlight key events and traits of American history and our heritage that shape and mold us as a people (Refer here). Dr. King’s birthday fits that intention, as this national holiday pays tribute to his influential role in the Civil Rights movement. The process to make King’s birthday a national holiday took fifteen years. Perhaps symbolic of the Civil Rights movement itself, it was an arduous and painstaking struggle (Refer here). The effort was noble and ensures a level of accountability in attending to King and his civil rights ideals for our nation’s future. My prayer is that Dr. King’s visionary life and beloved community ideal will shape our imaginations and mold our lives as a populace in the days and months and years ahead.

Certain qualities in Dr. King stand out now more than ever to me in terms of his import for shaping or molding our country’s imagination and character. They are as follows, along with quotes from some of his messages:

First, Dr. King highlighted and cherished the value of every person. No matter their walk of life, ethnicity, economic status, and more, every human being merited respect. His personalist philosophy and moral vision was on full display in his sermon on the Vietnam War, which he delivered on April 4, 1967 (one year to the day of his assassination). King declared:

I am convinced that if we are to get on to the right side of the world revolution, we as a nation must undergo a radical revolution of values. We must rapidly begin, we must rapidly begin the shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society. When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.[1]

Second, Dr. King called for and practiced enemy love. We find this feature of his life and work in his Christmas sermon delivered in December 1967:

We shall match your capacity to inflict suffering by our capacity to endure suffering. We will meet your physical force with soul force. Do to us what you will and we will still love you. We cannot in all good conscience obey your unjust laws and abide by the unjust system, because noncooperation with evil is as much a moral obligation as is cooperation with good, and so throw us in jail and we will still love you. Bomb our homes and threaten our children, and, as difficult as it is, we will still love you. Send your hooded perpetrators of violence into our communities at the midnight hour and drag us out on some wayside road and leave us half-dead as you beat us, and we will still love you. Send your propaganda agents around the country, and make it appear that we are not fit, culturally and otherwise, for integration, and we’ll still love you. But be assured that we’ll wear you down by our capacity to suffer, and one day we will win our freedom. We will not only win freedom for ourselves; we will so appeal to your heart and conscience that we will win you in the process, and our victory will be a double victory.

Third, Dr. King modelled non-violent civil disobedience and was willing to pay the price for it, as demonstrated again and again during the Civil Rights movement. In his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” (an open letter written April 16, 1963), King reasons:

My friends, I must say to you that we have not made a single gain in civil rights without determined legal and nonviolent pressure. Lamentably, it is an historical fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and voluntarily give up their unjust posture; but, as Reinhold Niebuhr has reminded us, groups tend to be more immoral than individuals.[2]

Rather than use coercive and violent hate, King and his colleagues catalyzed coercive, redemptive love that would win rights as well as win hearts in order to foster a just and equitable society for all people in pursuit of the beloved community.

Fourth, King realized that he could not accomplish the beloved community calling alone. This calling required solidarity involving a diverse array of people and he depended on God. As a Christian ecumenist, Baptist pastor and one of our country’s greatest public theologians, King turned to God for his strength again and again. The night before his assassination (April 3, 1968), in his last sermon titled “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop,” King shared with the congregation the following words (the text includes the congregation’s responses of affirmation):

Well, I don’t know what will happen now; we’ve got some difficult days ahead. (Amen) But it really doesn’t matter with me now, because I’ve been to the mountaintop. (Yeah) [Applause] And I don’t mind. [Applause continues] Like anybody, I would like to live a long life—longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. (Yeah) And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. (Go ahead) And I’ve looked over (Yes sir), and I’ve seen the Promised Land. (Go ahead) I may not get there with you. (Go ahead) But I want you to know tonight (Yes), that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land. [Applause] (Go ahead, Go ahead) And so I’m happy tonight; I’m not worried about anything; I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.

I encourage readers to watch the video clip of King’s closing words to the sermon that night. The footage is powerful and memorable (Click here).

I am extremely grateful for the legacy of Dr. King. He lived and served God and humanity during an extremely contentious and polarizing time. We need his vision now as much as we needed it then. We have some difficult days ahead in the church and society at large. What will inspire us? What and who will we celebrate or fear? Will the vision of the glory of the coming of the Lord inspire us? Will Jesus’ message and life of enemy love and non-violent civil disobedience set forth in the Sermon on the Mount that King embraced inspire us? Will the personalist vision that leads us to cherish every human life lift us up out of the reductionism that demeans and demonizes the other, whoever they may be? Or will hate and violence win out in our hearts and souls in the church and surrounding culture? As he declared in his Nobel Prize address in 1964, Dr. King firmly believed that “unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. This is why right temporarily defeated is stronger than evil triumphant.” May Dr, King’s vision of unarmed truth and unconditional love from above win out, conquering and extinguishing hate and evil in our souls and across the land.

_______________

[1]Martin Luther King, Jr., “Beyond Vietnam,” in A Call to Conscience: The Landmark Speeches of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., edited by Clayborne Carson and Kris Shepard, with an introduction by Andrew Young (New York: Warner Books, Inc., 2001), 157-58.

[2]Martin Luther King, Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” in The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr., ed. Clayborne Carson (New York: Warner Books, 1998), 191. For the classic study to which King referred, see Reinhold Niebuhr, Moral Man, Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and Politics, with a new foreword by Cornel West and an introduction by Landon B. Gilkey (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1960; new foreword, 2013).