In a response to a lot of the debate that followed Jennifer Fulwiler’s conversion story at Why I’m Catholic, NYT columnist Ross Douthat posed a question to atheists that I find hard to answer. Jennifer wrote that she abandoned atheism because she thought she was required to be a nihilist in a world without God, and, of the three propositions:

- God is not real

- Atheism logically requires nihilism

- Nihilism sucks so bad it can’t be true

She thought she was most likely to be wrong about #1. Then followed a lot of reading and blogging before her decision to convert, which you can review at Conversion Diary. A lot of atheists (me included) took issue with her confidence in premise #2, but Douthat’s post has taken some of the wind out of my sails. I’m paring down his thought experiment here, but you should click through and read the whole post:

Suppose, by way of analogy, that a group of people find themselves conscripted into a World-War-I-type conflict — they’re thrown together in a platoon and stationed out in no man’s land, where over time a kind of miniature society gets created, with its own loves and hates, hope and joys, and of course its own grinding, life-threatening routines. Eventually, some people in the platoon begin to wonder about the point of it all: Why are they fighting, who are they fighting, what do they hope to gain, what awaits them at war’s end, will there ever be a war’s end, and for that matter are they even sure that they’re the good guys?

…At this point, one of the platoon’s more intellectually sophisticated members speaks up. He thinks his angst-ridden comrades are missing the point: Regardless of the larger context of the conflict, they know the war has meaning because they can’t stop acting like it has meaning. Even in their slough of despond, most of them don’t throw themselves on barbed wire or rush headlong into a wave of poison gas. (And the ones who do usually have something clinically wrong with them.)… Instead, given how much meaningfulness is immediately and obviously available — right here and right now, amid the rocket’s red glare and the bombs bursting in air — the desire to understand the war’s larger context is just a personal choice, with no necessary connection to the question of whether today’s battle is worth the fighting.

Again, you ought to read the full post, but I think you can see where this is going. Why do atheists (like me, guilty as charged) think it’s reasonable to take meaning as a foundational premise in life, generally, but find it illogical for Douthat’s hypothetical soldiers to do the same thing at a slightly smaller scale.

Now, I can’t post a critique of atheists shying away from philosophy on Monday and then throw up my hands on Tuesday, so I’m going to kick around a couple ideas here, but I’m not really satisfied with any of them, so I’d welcome help in the comments.

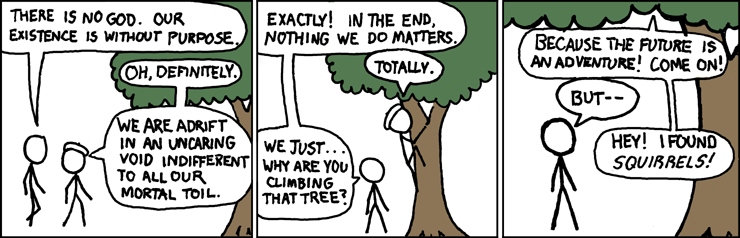

Objection 1: I have to throw in the obvious one. Living without meaning feels like living without a belief in the reality of physical objects. My every action gives the lie to my professed beliefs and I can’t even hypothesize about how I or anyone else would behave differently. This isn’t a very strong defense, I know, but it’s the readiest I have at hand. Before you dismiss this, I’d like to hear how you think I can/should justify my foundational belief in the reality of physical objects. And before you claim that any reasonable interlocutor will spot me that theorem, remember that Bishop Berkeley claimed God’s existence could be proven because a deity was required to keep Creation physical from moment to moment.

That was my knee-jerk defense, on to the more bizarre ones.

Objection two: The hypothetical is a poor image of the problem atheists are in. If the war turns out to be pointless, the soldiers might be foolish, but they are only wrong in that they mislabeled something as meaningful, not in positing that such a category exists. Humans tend to be oversensitized to patterns, but all our mistakes aren’t a disproof of order in nature or causality generally. Similarly, the idea that people can be mistaken about the meaningfulness of a particular event doesn’t mean that our mistakes about meaning-on-the-big-scale will be the same kind of mistakes.

Objection three: I think the soldiers may be wrong to ask the question at all at this intermediate level of human experience. Why should a war (and all the aggregated opportunities and constraints that come with it) be any more or less meaningful than an earthquake, especially to a conscript? I think of meaning as more of a telos/duty/geas kinda thing — something you’re called to. I’m meant for something, I don’t just pick up meaning like scout badges.

So what I’m meant to do is live according to my obligations to the best of my abilities in whatever circumstances I find myself. War, earthquake, high school are just different environmental constraints to for me to deal with (and some of these may be completely beyond my abilities — it’s an occupational hazard of not having a god to not send you more that you can handle). But the question of whether the backdrop is meaningful or good is only relevant to me insofar as I have the ability to alter it.

If I am a general or a politician, I’ve got a good deal more responsibility to make sure I’m not creating a world that makes it difficult for people to be moral — a world that requires sin eaters. Oh, and if I’m just me, I’ve still got to do my due diligence as a citizen in a democracy, but, even leaving that aside, I’ve got plenty of obligation to be going on with. Every action I take–even something as small as being brusque with a friend or stranger–can be a stumbling block for others struggling to be good.

I can see my duty plain, without understanding what metaphysical structure compels it. Stepping back into metaphysics is something I usually do just for fun, or as a change of perspective corrective to any bad habits I’ve picked up in my moral thinking.

UPDATE: There was some confusion in the comments, so you may want to check out the follow-up post: Too Sucky to be True.