While you’re all missing me, there are three games you might want to try that I’ve been playing at rationality camp.

The first two games are related. The first one is called the Calibration Game and the second is called the Updating Game. (Note: both those links start downloads of zip files). Both are trivia games, but, although you’re trying to get questions right, the focus is less on how knowledgeable you are and more on how good you are at gauging your own uncertainty.

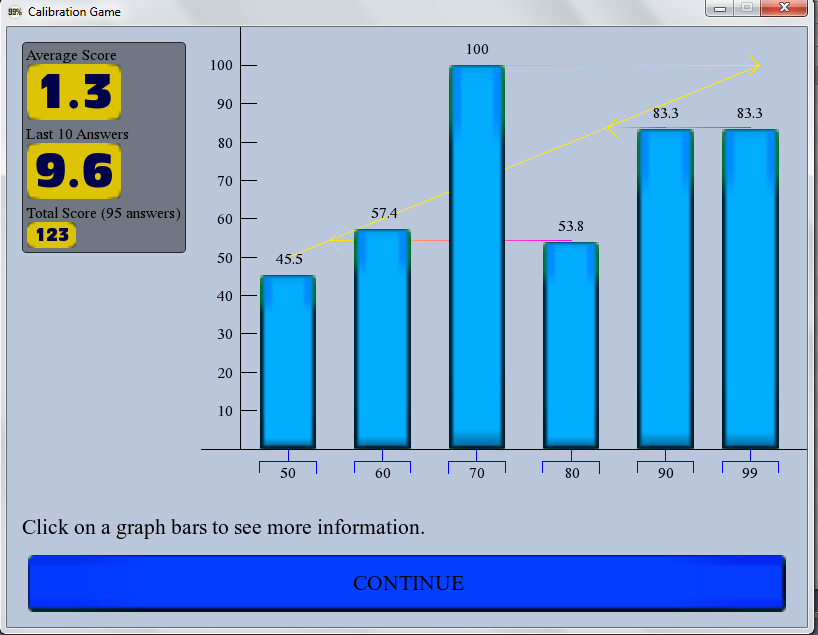

The Calibration Game asks you question with two possible answers and asks you how sure you are that you’re right. You gain or lose points depending on whether you’re right or wrong, and the change in your points is proportional to how certain you rated yourself. While you’re playing, you can see a graphical representation of your own accuracy about yourself.

If I were well calibrated, you would expect that when I’m 80% confident, I’d be right about 80% of the time. The bars should all hit a y=x line. That’s obviously still not the case (though, I will say in my own defense, my 70 and 80% bars are especially terrible because I’m very rarely 70-80 percent confident for any of these prompts, so any errors throw me way off).

The Updating Game also tries to make you aware of how badly calibrated you are, but using a different approach. Instead of picking from two answers, you get posed an open-ended question (i.e. What year did The Muppet Show premiere?) and you give an upper and lower bound for a 95% confidence interval. The game keeps track of how often the right answer falls into your specified range (it should be 95% of the time!).

The last game is the one I invented for LessWrong’s Be Specific prompt. I called it the Monday-Tuesday game.

On Monday, your proposition is true. On Tuesday, your proposition is false. Tell me a story about each of the days so I can see how they are different. Don’t just list the differences (because you’re already not doing that well). Start with “I wake up” so you start concrete and move on in that vein, naming the parts of your day that are identical as well as those that are different.

In CFAR’s implementation we paired off, picked two prompts from a hat, and tried to differentiate between two worlds, one in which a proposition was true and one in which it was false. The prompts varied a lot in how specific/quantifiable/etc they were, and my partner and I both pulled this one for our exercise:

On Monday, suffering builds character. On Tuesday, it doesn’t. Describe how Monday and Tuesday are different.

My partner suggested picking out two thousand people and randomizing half of them to torture horribly. Then he planned to give every subject one of the kinds of honesty tests you might find discussed in Bruce Schneier’s book Liars and Outliers. Everyone takes an exam and half of each group gets to grade their own papers. You compare the average score of the self-graders to the average score of the non-self-graders in each group to see how much they lied about their scores. In one world he’d expect that the people who were tortured were more honest than the controls, and in the other, he’s expect they did not differ significantly or that the torture victims were less honest.

I said that I’d expect that, in the world where suffering built character, that the people I most admired and wanted to model myself after would have suffered more relative to the general population. I thought about saying that, in the pro-suffering world, that people would use a lot of positive language to talk about suffering (more specifically that it would sound similar to the way non-athletes talk about exercise), but I wasn’t confident enough that this wouldn’t happen in the Tuesday world, too (because people have Panglossian tendencies) to use it as a criterion.

We ended up with pretty different approaches, since my partner was trying to construct the best experiment he could, practicality and ethics be damned, while I was trying to think, in the course of a normal day, what could I notice that would vary across worlds. I think both approaches can be helpful, especially since we don’t usually carry out experiments for all our beliefs, even if they’d help us be more accurate.

Do folks want to play along with that prompt in the comments? I guess you can also propose other True-on-Monday/False-on-Tuesday ideas and suggest ways that the two worlds differ. The funniest example from class was for “The Sun goes around the Earth on Tuesday” and the student said that, if all laws of physics weren’t believed to be different, he’d expect he’d find out that scientists were all in a conspiracy that he could infiltrate to perpetuate a big lie about how physics works.