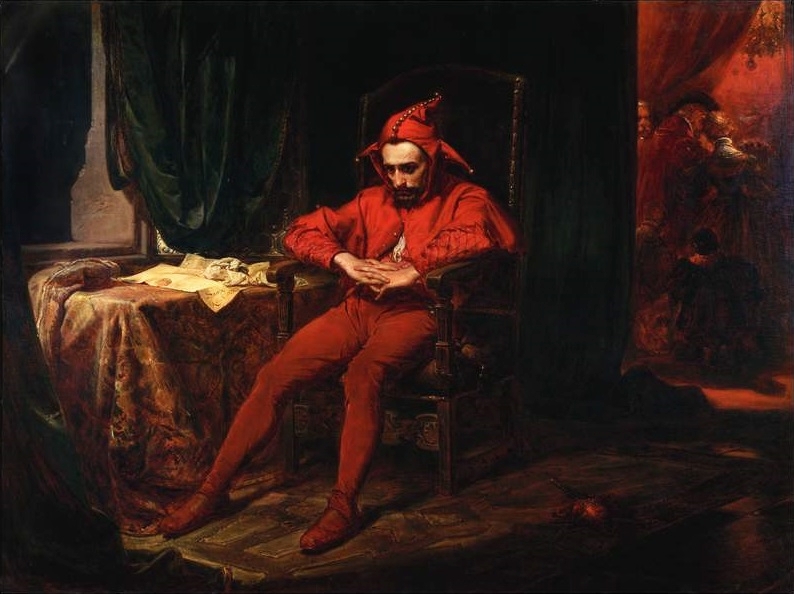

(interesting explanation of the wisdom of this fool at the link)

My friend Ilana Yurkiewicz is an excellent doctoring blogger, and I particularly appreciated one of her recent essays, “What’s so healthy about skepticism?” Her post about being deceived by a patient and deciding what lessons to learn from the encounter is excellent. I’ll blockquote a small bit here, but you should pop over and read the whole thing:

I had been deceived before, both in and out of the hospital walls. But it never bothered me as much as did then. There was something about how he did it. It was as though his plea was carefully constructed to play off my empathy. To tap into basic human compassion and twist it into a desired outcome. I wasn’t angry. In some strange way that I couldn’t fully understand at first, I felt hurt.

Maybe it was because when you are duped, you learn from it. You shift a little towards the opposite end of the spectrum of whatever quality flaw did you in. If someone plays off a lack of intelligence, perhaps you get a little bit sharper. If shyness a factor, you become a bit more assertive.

What bothered me is that if I were to learn from this situation, my lesson would be to become a little meaner.

I had trusted – trusted that a patient was in need, and that I had the ability to help that need. Our interactions with all patients are based on that trust, and we usually yield to it unthinkingly. I enter each encounter with a presumed belief that the patient and I are on the same side, working toward a shared goal of improving his or her health.

Maybe the next time, I wouldn’t trust so easily.

Ilana is describing something almost like an ethical heckler’s veto — when one unscrupulous person can ruin the system for everyone else, even if they represent only a tiny minority of bad actors. One act has the potential to quash a network of trust.

The suspicion that Ilana could learn from her patient would cause her to be less open to the next person she meets in the hospital, who now needs to think about how to manipulate Ilana differently, since presenting honest need isn’t distinguishable from feigned weakness. Signals get costlier, and we resent the person who forces us to humiliate ourselves to communicate the gravity of our need, and look for any easier way of getting what we want indirectly.

In order to prevent the manipulators from warping the whole system, our option is a kind of holy foolishness. A refusal to become wise, if wisdom is defined as harm-minimizing, and a willingness to be taken advantage of sometimes, in order to offer ourselves to be called upon in good faith. We offer our own disadvantage in order to offset the ratchet effect our loss-aversion would otherwise lock us into.

To be honest, though, I’m not really sure that this kind of willed openness can count as foolishness at all. As in yesterday’s example of “accurate” prenatal screening that was much better at identifying potential fetal abnormalities than in recognizing normal pregnancies, it seems like what’s primarily going on here is a problem of weighting two different outcomes of interest. Become a little meaner/less trusting is the right answer if you’re taking a minimax approach — where you minimize the maximum damage done in the worst case scenario.

But, if you assume that you will sometimes be taken advantage of, in the course of leading a pleasant, open-to-others life, then all you care about is whether you’re taken advantage of too frequently. Until patients start to manipulate you at some level above the threshhold you thought would be ok, there’s no need to close up in response to a lie. It’s just the cost of doing business pleasantly, just as sometimes getting wet is the cost of not carrying an umbrella everywhere.

P.S. I’ve been nominated in A Knotted Life’s 2015 Sheenazing Blogger Awards (named for the Venerable Fulton Sheen, a model of evangelism in new media). I’m nominated in “Smartest Blog” if you care to offer me your votes.

P.P.S. I saw Tom Hiddleston’s Coriolanus fairly recently, so all I can think of while asking for votes is:

Here come more voices.

Your voices: for your voices I have fought;

Watch’d for your voices; for Your voices bear

Of wounds two dozen odd; battles thrice six

I have seen and heard of; for your voices have

Done many things, some less, some more your voices:

Indeed I would be consul.