This guest post is written by Randal Rauser.

Christian theology has its share of whoppers (where “whopper” = a theological claim that collides with our moral intuitions, rational intuitions, or common sense). Among these whoppers we find the doctrines of the Trinity (How can God be one and three?!), incarnation (How can God become man?!), and substitutionary atonement (How can one person die for the sins of another?!).

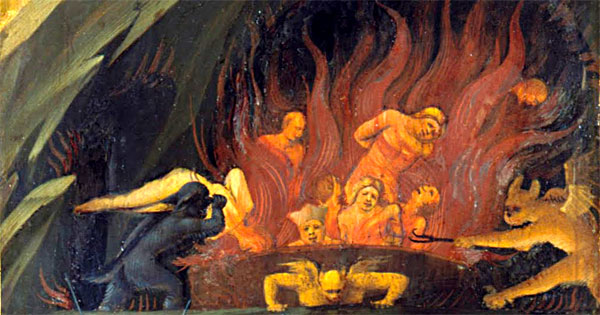

But there may be no doctrine from the mainstream body of orthodoxy more staggering than “eternal conscious torment,” that doctrine which proposes hell involves the never-ending unimaginably intense torment of people in body and soul.

(How can it be right to torture one person for eternity?!)

Take Adolf Hitler, for example. Hitler was a bad dude. Indeed, they don’t come any worse. But one might think that even in the case of Hitler, a few million (or billion?) years of unimaginable torment might be enough.

Our intuitions certainly suggest that eternal conscious torment is excessive. Okay, more accurately, my intuitions suggest that eternal conscious torment is excessive. But I’ve talked with enough people to know that I’m not the only one with these intuitions. So for folks like me, eternal conscious torment is also a whopper.

And that brings us to the next question: what do we do with this whopper?

In this article I want to consider one possibility in defense of eternal conscious torment. And just so you know where I’m coming from: I’m no fan of eternal conscious torment. But I also believe in giving serious ideas a fair shake. And since I defer to the wisdom of the Christian tradition, I’m obliged to concede that eternal conscious torment is a serious idea. And it deserves a fair shake.

So here goes. Let’s shake things up.

Our defense of this whopper of a doctrine begins with the following possibility: Could it be that we are horrified at the prospect of people suffering eternal torture in body and mind because we are insufficiently holy?

I know what you’re thinking. At first blush, that claim seems to contradict in the most direct terms what it means to be holy. You’re telling me I have a problem with torture because I’m not sufficiently holy? Are you kiddin’ me?!

I share that incredulity. It seems crazy to me to suggest that holiness is found in an indifference to the torture of others, even very wicked others.

And yet, as implausible as this idea might seem to be, you don’t have to look far to find theologians countenancing it.

Consider, for example, the case of J.I. Packer. I chose Packer because he doesn’t represent the worst of hard-nosed, misanthropic Calvinism (an easy target). Instead, in these passages Packer seems to be a humane, charitable, measured, pastoral and humble interlocutor.

And yet, despite all that, the underlying claim is shocking indeed.

To begin with, Packer takes on the problem by proposing the prospect of heaven offering a transformed divine perspective:

It is certainly agonizing now to live with the thought of people going to an eternal hell, but it is not right to reduce the agony by evading the facts; and in heaven, we may be sure, the agony will be a thing of the past. (Revelations of the Cross (Hendrickson, 1998), 168)

Packer is right about this much: if eternal conscious torment is a “fact” then it is not right to evade it. After all, a fact is a fact whether we like it or not. But we still must ask, is it a fact? That’s the question at issue. And those who have deep and powerful moral intuitions against this view have a good reason to think it might not be.

Packer’s main point comes next when he suggests that in eternity “the agony will be a thing of the past”. What’s this supposed to mean? I take it the idea is that once the redeemed are safely sanctified in heaven, they will be inured to the torment of those suffering in hell.

This proposal raises an interesting dilemma, one which we can illustrate with the case of Jones.

At present Jones is a Christian man who is moderately holy. While he struggles with sin, he also has moments where God’s light shines through. If you want to see the purest demonstration of divine love, altruism and sheer goodness shining through in Jones, all you need to do is look at the way he agonizes over the thought that his daughter Sarah, who left the church some years ago, will end up dying outside of Christ and going to hell to suffer forever. Jones weeps out of compassion over his daughter and as a result he is driven to pray for her regularly.

Now fast-forward to eternity: At this point Jones is made perfectly holy such that he now no longer struggles with sinful impulses. In this newly perfected state Jones is sinless, just like Jesus. Meanwhile, Sarah was indeed lost for eternity and as a result she now suffers unimaginable torment in hell.

Now for the question: Does this mean that Jones suffers immeasurably more for Sarah out of love, altruism and sheer goodness? You might think so. After all, her estate is unimaginably horrid and he’s now like Christ.

But au contraire, according to this account this fact causes Jones no consternation, no sadness at all. Indeed, Jones is now more joyful and happier than he ever could have imagined, even though this entails his daughter’s maximal suffering forever.

And how could this possibly be the case? Because, as Packer says, that’s just what it means to be holy.

Wait a minute. I know what you’re thinking: Holiness is measured by our indifference to the torment of others?

I take it that the paradox is rather glaring. When Jones is only somewhat holy he shows his best moments in his selfless love and care for his wayward daughter. But when he is perfectly holy and she is suffering horrendously, that selfless love and care will be gone, replaced by joy unaffected by the fact that she suffers unimaginably.

Huh?! How can it be that when he is partially holy Jones agonizes over the mere possibility that his daughter might be damned, but when he is fully holy he does not agonize at all over his daughter’s actual damnation? If I may avail myself of some gross understatement, it seems to me that this is a very substantial problem for the defender of eternal conscious torment.

At this point there are two possibilities one might countenance in reply. According to the first, God secures Jones’ perfect happiness in heaven by ensuring that Jones is never aware of his daughter’s fate. But surely this is an implausible suggestion, for it reduces heaven to a mere put-on in which eternal joy of those in heaven is secured by keeping hell out of sight and out of mind. This proposal reduces heaven to getting wired into the matrix so you are blissfully unaware of the agony elsewhere in the universe.

The second possibility is that holy Jones is fully aware of his daughter’s fate. Yeah, that’s right, I said fully aware. And the reason this fact causes him no suffering is because when a person is perfectly holy, so this view proposes, their compassion for the reprobate is diminished to nothing. In short, the more we are like Jesus, the less we agonize over the damnation of the lost.

But how could this be? An additional quote from Packer provides a reason:

The sentimental secularism of modern Western culture, with its exalted optimism about human nature, its shrunken idea of God, and its skepticism as to whether personal morality really matters—in other words, its decay of conscience—makes it hard for Christians to take the reality of hell seriously. The revelation of hell in Scripture assumes a depth of insight into divine holiness and human and demonic sinfulness that most of us do not have. (Concise Theology (Tyndale, 1993), 261.)

According to Packer’s analysis (as I understand it), Jones is presently agonizing over his daughter’s fate because he fails to appreciate the heights of divine holiness and the depths of human sinfulness. But when he is perfectly holy and so perfectly like Jesus, he will no longer suffer at all over her damnation. Indeed, if anything, it will be a cause for celebration as it reveals God’s holiness and his righteous judgment of human sin, including the sin of damnable Sarah.

You might object that Packer didn’t say that exactly. That’s true, he didn’t say that … exactly. But that is precisely the logic of his claim. To wit, imagine that Jones at present is informed in a revelation that his daughter will be damned in eternity. If Packer is correct in what he says here, this revelation should cause Jones no grief because God is perfectly holy and Jones’ daughter is egregiously sinful and wicked. Thus, the extent to which it does cause Jones grief is the extent to which he has failed to grasp divine holiness and human sinfulness.

It is difficult to know where to start with a view such as this. But I’ll make two quick points by way of reply.

First, God loved us and Christ died for us while we were yet sinners (Romans 5:8). To describe the Father heart of God, Jesus gave us the story of the Prodigal Son. That applies to all of us, not merely a subset of the chosen. (If, nonetheless, you insist on restricting it to a subset of the “elect” then all bets are off.)

Second, it seems to follow that growth in holiness (and Christlikeness) is expressed naturally in the self-giving love for others. Consider Paul’s agonizing declaration of his concern for his fellow Jews in Romans 9:3-4: “For I could wish that I myself were cursed and cut off from Christ for the sake of my people, those of my own race, the people of Israel.” Are we to think that the agony which drove this desire to sacrifice himself to save his people was born of a faulty grasp of divine holiness and human sin? On the contrary, isn’t the exact opposite the truth? Indeed, isn’t Paul most Christlike when he expresses this desire?

A person might reply: when people finally reject God, then God finally rejects them. But this sounds to me not like the unconditional love of God but rather like the tit-for-tat conditional love of this fallen world. And if we reject this logic and concede that God does love the reprobate eternally, would not the saved Christians in heaven love them as well? And if the saved love the reprobate, how can the unimaginable eternal torment of the reprobate not entail a diminution in the joy of those in heaven?

And if we conclude that it does then we face a dilemma: either heaven is not as joyful as we’ve been led to think or hell does not consist of eternal conscious torment.

About Randal Rauser

About Randal Rauser

Randal Rauser is Professor of Historical Theology at Taylor Seminary in Edmonton, Alberta. He is the author of many books, including Is the Atheist My Neighbor?: Rethinking Christian Attitudes toward Atheism (2015), The Swedish Atheist, the Scuba Diver, and Other Apologetic Rabbit Trails (2012), and You’re Not as Crazy as I Think: Dialogue in a World of Loud Voices and Hardened Opinions (2011). Rauser blogs and podcasts as The Tentative Apologist at randalrauser.com.