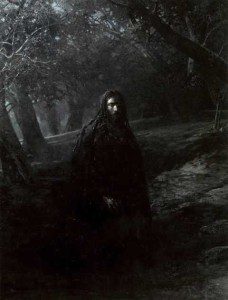

As I wrote in my last post, many theologians throughout history have been freaked out by the Gethsemane account. They tended to rely on the “two natures” (divine and human) doctrine of Christ, in order to protect the “divine nature” of Jesus from the emotions, anguish, and temptation of the Garden of Gethsemane. Jesus may have been anxious, in his human nature, but not in his divine nature. He may have been sorrowful in his human nature, but not in his divine nature. But in modern theology, this tendency to carve up the person of Jesus into two separable “nature,” and then allocate the “weakness” to the human side, is far less prevalent (thankfully!).

Karl Barth, for example, has urged that we not overlook the genuine humanity of Jesus as encountered in the Gethsemane account. For Barth, Christ was the “new Adam,” the covenant figure who mediated between God and humanity and who brought about reconciliation between God and the cosmos. Barth interpreted the Gethsemane account as mirroring the wilderness temptation

story, but with an important difference. He writes,

In the [wilderness] there is not even the remotest glimpse of any hesitation or questioning on the part of Jesus Himself. Self-evidently and with the greatest precision the tempter is at once resisted. But then it was only a matter of continuing without deviation on the way He had entered at Jordan. Now he had to face the reckoning. Now [in the Garden of Gethsemane] He was confronted with the final fruit and consequence of what He had begun.[1]

In Barth’s view, the dread of the event he was about to undergo, the crucifixion, was not just the fear of physical pain and death, but had more to do with the alignment of the will of Satan with the will of God. That is, the cross would in effect mean that the powers of evil had taken up ruler-ship over the world; somehow, the history of God’s redemption would include within it Satan’s victory (even if only temporary).. So Jesus prays, in the garden, “that for the sake of God’s own cause and glory the evil determination of world-occurrence should not finally rage against Himself, the sent One of God and the divine Son.”[2]

Jesus prayed to discover the will of God and was intent on aligning his own will with God’s will—knowing also that God’s will was directed toward the reconciliation of God with creation and with the salvation of humanity. In Gethsemane, we encounter both the obedience and the freedom of Christ. While Jesus desired to obey the will of God and pressed his way into complete obedience, even unto death, the will of Jesus was not automatically folded into the will of God. As Paul Dafydd Jones writes, engaging Barth’s discussion of Gethsemane,

Christian theologians cannot bury the possibility that Jesus might have been overcome and that the project of reconciliation might have miscarried. The theologian must take with full seriousness Jesus’ quandary in Gethsemane as he asks, “Does all this have to happen?”[3]

Jones might be pushing Barth a bit further than he actually went, but it’s a profound question nonetheless. Could we fathom, even just for a moment, on this Good Friday, the possibility that Jesus might have been overcome? That the “temptation” of the second wilderness (Gethsemane) might have simply been too much to bear?

[1] CD IV/1, p. 265.

[2] CD IV/1, p. 269.

[3]Paul Dafydd Jones, “Karl Barth on Gethsemane,” International Journal of Systematic Theology 9, no. 2 (2007): p. 159. See also CD IV/1, p. 264.