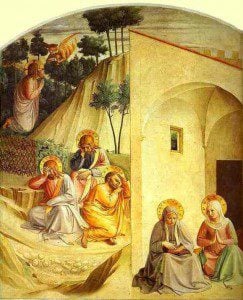

The Garden of Gethsemane story has given theologians fits.

Many of them, particularly in the early-to-high medieval period, just didn’t know how to resolve the tension of a Jesus, the divine Son of God, who seemed to undergo such grief and sorrow. And what concerned them even more was the suggestion that Jesus’ will, clearly distinguishable from the Father’s, might have conflicted with God’s will: “Not my will, but yours…” Did Jesus really long for the cup to pass? Might the trauma of the anticipation of his suffering have overcome him? Could the mission have failed–lain stillborn there in the Garden–awash in the blood, sweat and tears of Jesus?

This tension actually led some theologians to “interpret away” the troubling implications of the narrative.

In an illuminating article on medieval interpretation of Gethsemane account, Kevin Madigan[1]offers a number of examples:

Ambrose warned his readers to “not open your ears to those treacherous people who suggest that it was out of infirmity that the son of God prayed, as though he had to ask for something that he was powerless to achieve himself.”

Jerome urged, “Let those who think that the Savior feared death and in fear of his passion said, ‘Let this cup pass from me’—let them turn pink with shame.”

Aquinas suggested, “Since Christ could do all things, it does not seem right that he should petition anything from another.”

Many theologians were inclined to relegate the “emotions” and “weakness” of Jesus to his human nature, not to his divine nature; the vulnerability of Jesus must be attributed to his humanity, not to his divinity. They had creative ways of manipulating the story to alleviate their theological anxiety. Madigan observes Jerome’ strategy: “[i]t is one thing to be saddened,” and “another to begin to be saddened.” Jesus had “half-passions,” not full passions, like you and I. The divine nature served, supposedly, as a kind of emotional backstop to keep Jesus from becoming too wimpy and weepy. It was inconceivable for many of these theologians, so committed as they were to “divine impassibility” (God is unaffected emotionally by events or persons outside of God and beyond his control). God simply cannot suffer. Enough said.

But this commitment led to a misinterpretation of Gethsemane and an insufficient theology. There simply is no strong biblical reason to let a (Platonic) idea of divine impassibility trump the theologically and pastorally powerful story of God’s entrance into history as Jesus the Messiah, in which he undergoes serious grief, anxiety, and suffering on our behalf. The implication is not just that Jesus suffers–in his humanity–but that as the unified person Jesus–who shares divinity with God and humanity with us–God also suffers in Jesus.

Modern theologians have been much more willing to live with the tension created by the implications of a Jesus who is not “divided up” but in and through whom God experiences the passion, too.

Catherine LaCugna, in her important book, God For Us, puts it well:

…the suffering and death of Jesus Christ must condition all assertions about God’s love. It is inconceivable that the God who chooses self through another would not suffer, that the God whose whole existence is tied up with the redemption and liberation of the creature, would not suffer with the creature, that the God who is Love Itself (Ipsum Amore) would not suffer on account of this love. God’s whole energy is devoted to redistributing the goods of the earthly economy into the divine economy, so that every tear will be wiped away, and all will be sister and brothers in the one household of God (398).

She is right. And Gethsemane is exhibit A of the love of God in Jesus, and the willingness of Jesus to push through the trial so as to match his will with the will of God, knowing that it would mean the voluntary suffering of both Jesus and the Father–on our behalf.

[1]Kevin Madigan, “Ancient and High-Medieval Interpretations of Jesus in Gethsemane : Some Reflections on Tradition and Continuity in Christian Thought,” Harvard Theological Review 88, no. 1 (1995).