First, let’s just acknowledge that God is not literally male. Or female, for that matter.

The historical flesh-and-blood Jesus was biologically male. No one (or hardly anyone) really disputes that.

But God? YHWH? Yahweh? The Creator of the universe? The Alpha and the Omega? The omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent One? The Being-Than-Which-None-Greater-Can-Possibly-be-Conceived? The Uncaused Cause?

Most theologians agree that God is not literally “sexed” and furthermore, we cannot assume that the language that we use to refer to God (even that language given through divine revelation) literally and adequately refers to God in some univocal way of correspondence.

The language we use to refer to God, to pray to God, to address God, to speak about God, is analogical. God references function like analogies do–they are meaningful and they are referential, but there is always a recognizable gap between the word/title/ and that to which it refers. The referent.

Problematically, though, the long historical and consistent use of male-dominant images to refer to God (and quite a bit of those come from the Bible–which unarguably reflects its patriarchal context), has sort of tricked many people, if only by a kind of osmosis or subtle, innocent indoctrination, into believing that God is actually male. Or at least more male than female. Or more “masculine” than “feminine.”

Indeed, some pastors and theologians insist on a primarily male-orientation in God. Many certainly insist on the absolute necessity of calling God by the male-dominant pronouns and references that we find in the Bible.

But, if we understand the way that God-references actually work, and if we acknowledge that God’s nature and being lies beyond the capacity of our finite language to adequately represent, then we should be very wary of any approach to God-references that demands conformity to any particular sexed or gendered references to God. And, we should feel much freer to incorporate other images and references to God that reflect the mystery of God, the relationality of God, and the love of God for all persons. And we could even limit ourselves to images and titles from the Bible and still develop a much more sex/gender inclusive and dynamic image of God and vocabulary for our references.

Now, all that said, I want to put forward a rationale for referring to God as Father, that I came across recently in the book Feminist Biblical Interpretation.

In her essay on Matthew’s gospel, Martina Gnadt shows that the reference to God as “Father,” which is commonly used in the gospel of Matthew (and in the gospels generally), must be understood in the tense context of the Jewish-Christian (and Gentile-Christian, for that matter) relationship to the Roman Empire.

Of course, one important reason for the use of “Father” in the gospels is because the primary character of the gospels is Jesus, the “Son of God.” Jesus refers to God as his “Father,” but he also encourages his disciples to do the same. So we have the famous “Lord’s prayer,” in the Sermon on the Mount text, in which Jesus begins with, “Our Father in heaven…”

There is a basic relationality that is expressed here and throughout the gospel, both in terms of Jesus’ specific relationship to YHWH, but also in terms of the disciples’ relation to YHWH. They can address God, request of God, and even depend on God for daily provisions. God is not unapproachable or unattainable. God is Father.

This is a pretty big deal, because this means that the Father-status of God makes it possible for the children of God to be released from their anxiety about their basic needs. As Gnadt put its,

The heavenly Father’s most important characteristic is that one can depend on his care for all creatures. Building on this, the Gospel of Matthew calls for freedom from anxiety (6:24-34): for day-by-day resistance to submitting to mammon, that is, to a life defined primarily by concern about food, drink, and clothing, a life in which a real dependency on these goods has the last word, enslaving those who live in this way (v. 24). For the Matthean churches such a life is pagan and lacking in faith (vv. 30, 32). By appealing to their heavenly Father’s dependable care, these churches reject such a life and, instead of depending on priorities determined by someone or something else, they establish their own priorities: the kingdom and righteousness of God, their king (v. 33) (p. 609).

With the political and economic context of the Roman Empire in mind, Gnadt suggests that the term “father” has less to do with confirming and perpetuating patriarchy than it does with the churches in Matthew, led by the teachings of Jesus, to position themselves and their daily life in resistance to the imperial powers.

To rely on the power and the “mammon” provided by the Empire would be to undercut if not eliminate the possibility of a subversive stance against its injustices.

For these early Christians, God was their Father: not Caesar, not the Emperor, not the local Roman governor. Even the persistent patriarchy of the household situation was challenged or upended by the emphasis on God alone as Father: “The churches have only one master and teacher, Christ, and only one Father, God. Ultimate authority is ascribed to Jesus, as the conclusion to the Sermon on the Mount states programmatically.” (608).

Empires-back then and still now–use human anxiety to garner the attention and submission of their subjects. They offer protection, security, comfort–which is to say “mammon”–the only price for that security is unconditional obedience and quiet submission. Trust in God as Father–as the one who provides–cuts the link between human anxiety and the control of the Empire because it dissolves anxiety into prayer, service, and confidence.

Gnadt concludes her reflection on God as Father with this:

The place in which the Matthean churches serve God, as the Sermon on the Mount portrays it, is everyday life in the patriarchal world, with its claims and power relationships, its demands and tribulations. The concept of God as Father does not spring the bounds of this context, but at a decisive point it breaks it open: set in opposition to the imperial father’s power claim, which reaches right into people’s daily lives, is the claim of the heavenly Father. His power is expressed in his knowledge and in his active care for the needs of his “children” (6:8, 32). Care and forgiveness are his gifts, gifts that they desperately need and that they are able to expect and request confidently from their heavenly Father (611).

So “Our Father” can have an anti-patriarchal, subversive tone to it. Like calling God “king,” it stakes out a claim for the believer with respect to which “powers” have ultimate authority. It can also be a very egalitarian and democratic claim, because it puts all people on the same level; all as equally loved and deserving of respect under the loving authority of God.

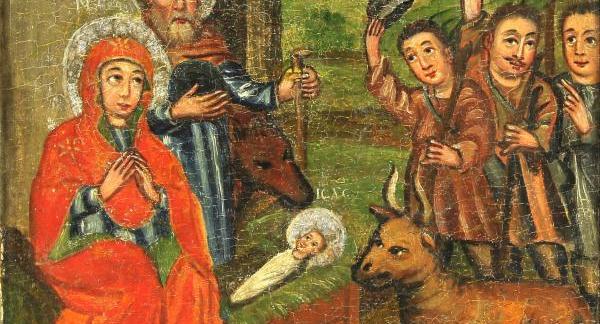

Image Source (slightly cropped)

Stay in the Loop! For more discussions and posts on theology and society, like/follow Unsystematic Theology on Facebook