Looking for a provocative and insightful way of putting an important question about God and our conceptualizing of God?

You can find one in Neil Gillman’s excellent book, The Death of Death: Resurrection and Immortality in Jewish Thought. I’ll interact more with Gillman’s work in a subsequent post, but for now I leave you with this:

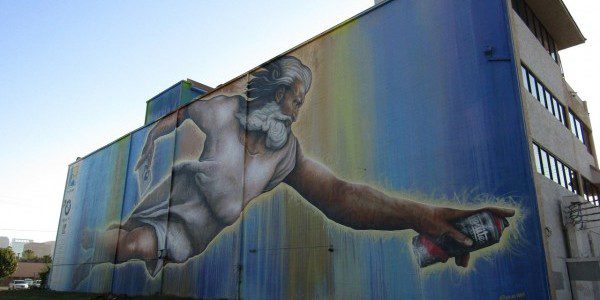

[Abraham] Heschel’s view that Torah is midrash [human interpretation] is designed not to demean Torah, but to preserve God’s transcendence. What is demeaning is to portray God as literally doing the things that human beings do. That is idolatry, the cardinal sin in Judaism.

Instead, God must be portrayed through metaphors which stem from genuine human experiences of God’s work in nature and history and in the personal experience of individuals and communities. A metaphor is never literally true: The lion is not literally “king” of the beasts nor does one want to weigh a “heavy” heart or measure the “cruelty” of the month of April. But metaphors are also more than useful fictions. They vividly and dramatically capture analogies between the more elusive dimension of our experience and the aspects of that experience that can be expressed in human language. They are revelatory. They let us see what would otherwise escape us.

To say that the way we characterize God is metaphorical is to say that our images of God are also “within” the myth, for a myth is a way to organize an ensemble of metaphors. Thus the question: Do we invent God? Or do we discover God?

The only answer is that we discover God–and we invent the metaphors. Which comes first? It depends. Sometimes the metaphor enables us to experience God. “God is my shepherd…” helps me identify a certain quality of my experience of God, God’s nurturing. But someone, somewhere had an experience of nurturing that came from a reality outside and beyond him or her and that person coined the metaphor of God as shepherd. The same with the metaphors of of God as “rock of Israel,” as person, as lover, parent, or judge; the same with the darker metaphors of God as abusive, unfair, abandoning and punitive.

It bears repeating, if only because it is so often misunderstood, that this theological approach does not eliminate God from the picture. God still remains, but humans cannot perceive God’s presence and activity in their purity since there is no objective demonstration that God is or of what God does. There are only human perceptions of these realities. It is with these that we must work. (32-33)

I (Kyle) will say, in closing, that as a Christian theologian–while I accept the thrust of Gillman’s well-stated point here that we “discover God–but invent the metaphors,” for me the incarnation of God in Christ complexifies (or even, let’s say, downright “interrupts”) the notion that God cannot be said (without committing idolatry) to “literally do the things that humans do.”

For more theology and society, like/follow Unsystematic Theology on Facebook