When I taught theology at an evangelical seminary, I ended every lecture on heaven/hell by posing the option of “hopeful universalism.”

To be a hopeful universalist is to assert something like the following:

I don’t know whether in the end God is going to save everyone, but I sure as hell (!) hope so, and I will pray to that end, and I believe that on the basis of God’s grace and mercy and love that it make a lot of sense if kindness, generosity, grace and mercy have the final word.

The hopeful universalist poses a question like that of Hans Urs von Balthasar: Dare We Hope that All Men (sic) Be Saved?

I regularly concluded that lecture with the powerful statement from Karl Barth, which articulates the rationale for hope in a universal restoration of all people to God and to each other:

For there is no good reason why we should forbid ourselves, or be forbidden, openness to the possibility that in the reality of God and man in Jesus Christ there is contained much more than we might expect and therefore the supremely unexpected withdrawal of that final threat…If we are certainly forbidden to count on this as though we had a claim to it…we are surely commanded the more definitely to hope and pray for it…to hope and pray cautiously and yet distinctly that, in spite of everything which may seem quite conclusively to proclaim the opposite, his compassion should not fail and that in accordance with his mercy which is “new every morning,” He “will not cast off forever” (Lam 3:22). Church Dogmatics, IV/3, pp. 477-78

Posing the very possibility of a universal salvation through or because of the grace of God through Jesus Christ, gave many of my evangelical students a palpable sense of relief. Perhaps God is that loving, that merciful, that kind.

But there were always a few that got a little perturbed, or even visibly angry by the idea! To them, it seemed somehow unfair that God would just save everyone, no matter what they did in life, no matter whether they “accepted Jesus as Lord and Savior,” no matter whether they sacrificed anything for God.

Of course, there were other objections, too: If everyone gets saved in the end, why evangelize? Why witness? Why go to seminary? (and why go into debt to get a seminary degree!) and so on.

Interestingly, this is formally the same logical problem that Calvinists face, because if God has pre-ordained those who are elect and those who are non-elect (predetermined whom will be saved and who won’t be), then why do anything at all?

But there’s actually a lot more motivation, in my view, for a Christian universalist to act positively in response to God’s universally saving grace, than there is for a Calvinist to act positively in respond to a God who only saves an elect few. The Christian universalist responds to a gracious and loving God, the Calvinist to a capricious and vengeful God.

Further, some raised the challenge that a universal salvation seems to diminish the work of Christ on the cross, a challenge which goes something like this:

Christ died so that people who trust in Christ for forgiveness can be saved. But if everyone is saved anyway, then the mechanism of atonement is meaningless, because the door is opened wide for salvation regardless of what people do in response to that mechanism.

But once you’ve seen the beauty in a potential universal salvation (which, for a conservative evangelical, can be remarkably difficult to see for the first time!), that objection seems rather silly, or at the very least bad calculus. Why would extending the work of Christ’s atonement universally be an undermining of the value of the cross? Doesn’t expanding its effectual power have the opposite effect –i.e. enhancing and magnifying the glory of Christ’s work?

The more substantive objection from within orthodox Christian theology to Christian universalism, in my view, has to do with free will. Can and will God save everyone, without diminishing or undermining the free choice of all individuals? In other words, will God get what God wants: the salvation of all persons (see 1 Tim. 2:4; 2 Peter 3:9), or might the preservation of free will mean that not all persons will be saved, because some will eternally refuse the offer?

*There are substantive objections from outside Christian orthodoxy, which suggest that Christian universalism is inherently imperialist and patronizing. But I’ll save that for a later post.

What concerns me most about Christians who cannot countenance the possibility that God might choose to save everyone is when that very possibility agitates them; when they get downright angry about it.

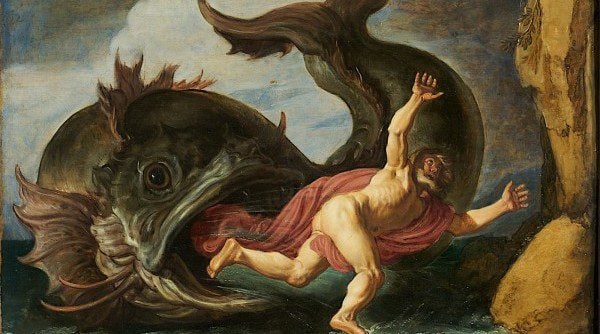

But anyone who gets agitated by the possibility of universal salvation through Christ, who does not experience the possibility as an outcome for which we should hope and pray, needs to re-read the story of Jonah.

Jonah explained to God that he fled to Tarshish rather than go do Ninevah to share God’s message with them, because he knew that God was gracious “and merciful, slow to anger, and abounding in steadfast love, and ready to relent from punishing” (Jonah 4:2). Jonah got angry with God because of God’s plans to save Ninevah, and God asks, “Is it right for you to be angry?“

The right answer, of course, is no.