In my Public Theology class last night, we discussed–albeit too briefly–Pope Francis as a public theologian and, as an example of public theology, his recently released Laudato Si,’ a 192 page Encyclical on the imperative to address climate change (pleasantly subtitled: “On Care for Our Common Home.”

When discussion public theology, we academics tend to be drawn to discussing the writings of established academic public theologians (whether Karl Barth, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Reinhold Niebuhr, or James Cone, Catherine Keller, and Shawn Copeland, or so many others).

It should not be missed that often the most impactful public theologians are not those working and writing within the cloisters of the academy (although those I have mentioned have done theology both for the academy and outside of it), but those who are on the frontline, where Christianity and the Church meets up with the public of the general society.

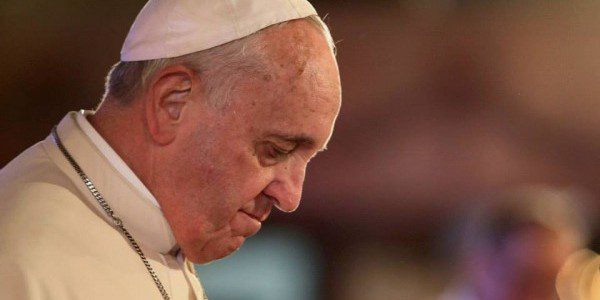

In this sense, there is no more prominent example I can think of than Pope Francis–who in fact may be the most impactful public theologian in the world today.

While atheism and various expressions of non-institutional religiosity is certainly on rise in the developed world, religion still has a lot of sway. This is why, if we are to address the urgent issues facing society, we need religious leaders to speak into those issues.

As Duncan Forrester, one of the leaders of the contemporary public theology discipline notes,

It is not difficult to see why intelligent, liberal people might wish to exclude religion from public life. Religion has, indeed, often been divisive. Religious views are frequently presented as if their proponents have some privileged access to the truth which exempts them from any need to show how the policies they propose might be for the general benefit. Religion often goes with a kind of naive idealism which pays scant respect to the fact of the case and the constraints within which politics must operate: absolutism in politics can be very destructive; simplistic utopias can be very dangerous. All that may be admitted.

And yet, there is another line of argument that suggests that a public sphere from which religion is excluded is deprived of a great source of determination, hope and the vision ‘without which the people perish.’…

Has secular liberalism shown itself as effective in naming and resisting great evils and appealing to conscience as religious movements, often small minorities, have shown themselves to be? Religion can generate passion in politics but, although passion can be destructive, a politics where ‘the best of all lack conviction’ becomes a very evil thing. (31)

Some might yawn at the image of the Pope and the President conferring about the social problems of the U.S. and the world. They might wonder why, in this day and age, we need religious figures to speak into issues of concern for everyone. And of course the conflation of religion and politics, or the use (or manipulation) of one by the other, can often in fact be problematic. But it’s a necessary problem to work through.

Whether one agrees or disagrees with the positions espoused by our religious leaders, if we are going to adequately address the challenges that confront us, we need theology in the public sphere.

For more posts and discussions on theology and society, like/follow Unsystematic Theology on Facebook