Probably the most common critique levied against evolutionary theory by creationists is the issues of “transitional species.” If Darwin’s theory is right and species transition into different species gradually and over long periods of time, why don’t we see more evidence of these transitional forms in the geological record?

Or another way to put it: Why are there so many “gaps” between species, if all species are ultimately interconnected

and can be traced back to a single life form?

Michael Shermer, in Why Darwin Matters, notes that Darwin himself recognized this question as the most potentially challenging to the theory of evolution. Where are all the transitional fossils? Or, as Darwin put it, the “intermediate links”? Shermer explains:

One answer to Darwin’s dilemma is the exceptionally low probability of any dead animal’s escaping the jaws and stomachs of predators, scavengers, and detritus feeders, reaching the stage of fossilization, and then somehow finding its way back to the surface through geological forces and unpredictable events to be discovered millions of years later by the handful of paleontologists looking for its traces. Given this reality, it is remarkable that we have as many fossils as we do.

There is another explanation for the missing fossils. Ernst Mayr outlines the most common way that a species gives rise to a new species: when a small group (the “founder” population) breaks away and becomes geographically–and thus reproductively–isolated from its ancestral group. As long as it remains small and detached, the founder group can experience fairly rapid genetic changes, especially relative to large populations, which tend to sustain their genetic homogeneity through diverse inbreeding. Mayr’s theory, called allopatric speciation, helps to explain why so few fossils would exist for these animals (10-11).

More recently, scientists Niles Elederidge and Stephen Jay Gould examined the fossil record with Mayr’s theory and observation in mind. They realized that the so-called “gaps” in the record are are “not missing evidence of gradual changes,” but actually constitute “evidence of punctuated changes” (11). Thus we have the theory of “punctuated equilibrium.”

By the way, Gould would later express regret at the way punctuated was misunderstood and has been misused; these bursts of genetic change and evolutionary activity are only punctuated” relative to the very long periods of time involved in the entire history of evolutionary life. In any case, Shermer goes on to explain that typically,

Species are so static and enduring that they leave plenty of fossils in the strata while they are in their stable state (equilibrium). The change from one species to another, however, happens relatively quickly on a geological time scale, and in these smaller, geographically isolated population groups (punctuated). In fact, species change happens so rapidly that few “transitional” carcasses create fossils to record the change…

Of course, the small group will also be reproducing, following the geometric increases that are observed in all species, and will eventually form a relatively large population of individuals that retain their phenotype for a considerable time–and leave behind many well-preserved fossils. Millions of years later this process results in a fossil record that records mostly the equilibrium. The punctuation is in the blanks (11).

Even with the relative scarcity of “transitional fossils” (relative compared to fossils reflecting the state of equilibrium of a more stable species), geologists have uncovered numerous examples. For example, Shermer notes there are “now at least eight intermediate fossil stages identified in the evolution of whales.”A grand example of a transitional species is the Ambolocetus, otherwise known as the “walking whale.” This creature, early ancestor to the modern whale, could both walk and swim and gives evidence that whales started their evolutionary life on land.

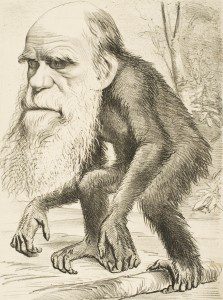

But our own fossil lineage may contain the most extensive evidence of transitional forms, because there are “at least a dozen known intermediate fossil stages since hominids branched off from the great apes six million years ago.” And the kicker, Shermer tells us, is that “geological strata consistently reveal the same sequence of fossils.”

In other words, the story (Darwinian theory of evolution) consistently holds up as the best explanation of the converging lines of evidence.

Stay in the loop! For more posts and discussions on theology and society, like Unsystematic Theology on Facebook!