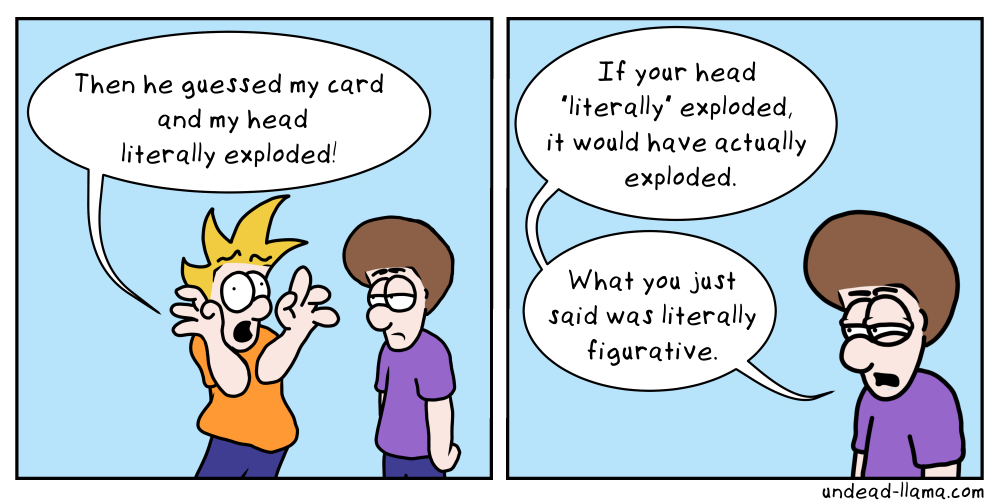

“Do you take the Bible literally?” asked an inquisitive church member not realizing that a simple, yet more loaded question could not be asked. If I answered “Yes” I would be implying that Christians must do everything written therein literally. By saying “No” I would be impinging upon the reliability and authority of the Bible. Of course, anyone involved in such a discussion knows the matter is far more complicated than those two options. And often it revolves around definitions. What do we mean by “literal” and how does that affect our interpretation? One question at a time.

Literally Literal? Or Literally Figurative?

One approach is to view the Bible as “historically literal”—that what the Bible purports to have happened actually happened in that exact way. This line of thought suggests that the authors intended to write history in the same way that a twenty-first century scholar would. More than that, such a view assumes that they had the materials in hand to accomplish such a feat. But contrary to these assumptions, historiography (how history is written) is a modern construct and applying it to ancient writers is anachronistic and unfair to their intentions. Biblical writers were not attempting to write an unbiased history of what occurred. Rather, they compiled a theologized history—that is, a history from the viewpoint of a faithful people reflecting upon a saving God.

Even if the original authors were writing with unbiased intent, they did not have the primary materials to accurately convey historical events. Many things described in the Bible were reconstructed from oral transmission since most events were not recorded for posterity. For example, it’s not as though there was a stenographer capturing the wilderness wanderings. So we should not be surprised when there are tensions (or to put it more boldly, “contradictions”) in the text. After all, the authors were not concerned with transmitting events exactly as they happened. Rather, they incorporated historically based events into their overarching theological themes and shaped them into a coherent whole. A brief look at the Synoptic gospels (Matthew, Mark and Luke) reinforces such a position. When Matthew says that Jesus taught on a mountain (Matt 5:1) and Luke says he “came down and taught on a level place” (Luke 6:20), is one of them just wrong? No, it means there is more to each author’s presentation than meets the eye and it calls for a little investigation.

All of this is to say, we should be wary to take the Bible as “historically literal” because we open ourselves to criticism when a Biblical account seems to be contradicted by other “histories.” What we can say is that the Bible is based in history and contains some historical accounts, but at the end of the day the authors were concerned more with the theological message than the historical accuracy.

Well if we don’t mean “historically literal” perhaps we mean “instructionally literal.” That is, when the Bible makes a command, we take it literally and do it—no questions asked. On the one hand, such a literal view has its appeal. It removes any interpretation from our part and places it firmly in God’s hands. There is no need to justify our actions because God has the final authority. No gray area means no debate. Sounds great right?

The problem with this literal view is that it does not account for how the laws function in the Bible. For example, what do we do with the Old Testament laws? Unfortunately, many too easily dismiss Old Testament laws by saying we live under the New Covenant (I’ve already addressed that in a previous blog). Also, what do we do with cultural laws—that is, laws whose context can be traced to a specific time and place but whose impact is lost on a different, modern culture? A most obvious example is Paul’s command for women to dress modestly, which excludes braided hair, gold jewelry or pearls (1 Tim 2:9). Yet even the most staunch advocate for literal adherence to the Bible probably would concede that this command was culturally focused and described prostitutes in Paul’s day. Yet, literally interpreted, women should not wear jewelry or braid their hair. But such an understanding would seem to be ludicrous by today’s standards. Also, I wonder how many people take seriously Paul’s command to prepare a room for him (Philemon 22) or how many are still praying for Paul’s proclamation of the gospel (Eph 6:20)? Or, more graphically, when Jesus recommends gouging out your eye or cutting off your hand to avoid sin (Matt 5:29-30), who, except the most ascetic among us, would literally follow such a command?

Toward Better Interpretation

Hopefully my point is clear—patently accepting biblical stories and laws as literal is not a correct appropriation of Scripture. These texts are set in a context that needs investigating before appropriating. This literal approach does not take into account genre, metaphor, hyperbole, etc. Perhaps more egregious is that this literal approach does not consider authorial intent. Though we may never know exactly what an author was thinking, we can generally deduce a probable theological theme. Thus, a literal interpretation is not always a correct one (though sometimes it is). By saying that I don’t always take the Bible literally should in no way imply that it is not the main source of truth that God has revealed to humanity. The Bible is true and does not need to hold up under factual and verifiable scrutiny. It reveals God’s relationship with God’s creation and is not a handbook of World, Israelite, or Christian history.

Correctly understanding Scripture requires a Spirit of wisdom coupled with a proper understanding of context and background. To such ends, each new generation needs to allow the Bible to speak anew to the needs of the community. May we take the Bible seriously, even if we don’t always take it literally.