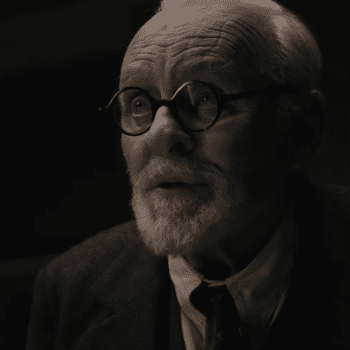

No one does crazy like Joaquin Phoenix, and the actor is utterly mesmerizing here. And make no mistake, his Joker does some really terrible things. The character is perhaps as villainous as he’s ever been on screen.

But it takes him time to get there. When we first meet Joker, he’s simply Arthur Fleck, a guy with serious mental issues and saddled with some woefully dispiriting challenges.

He’s not a bad man, though he does have urges to do bad things. But he takes his medication regularly, sees his legally mandated counselor and tenderly cares for his invalid mother. And maybe, with a little help and a little affection, Arthur might’ve lived a quiet life without hurting anyone.

But systematically, everything that Arthur needed for that quiet life is ripped away from him. Budget cuts strip him of his therapist and meds. Arthur discovers that his wife, and his past, were different than he imagined they were, sending him careening into an identity crisis.

But mostly, we see Arthur victimized. He’s beaten. Mocked. Unjustly accused. Unfairly framed. It’s as if he’s the poor new kid in a playground filled with bullies.

But it’s not just the bullies who are at fault. It’s the bystanders, too. Arthur’s a weird guy, no question. He’s the sort of man that, even at his best, most of us would walk across the street to avoid. But he, like every other human being, has a longing—a need—for connection. We are social creatures, and Arthur’s no different in that respect. But because he is so different in other ways, he’s a pariah, a misshapen creature society deems worthy to be discarded and forgotten.

When Joker’s trailer came out, a lot of people noted how much it looked like Martin Scorsese’s classic Taxi Driver, and the comparisons are valid. (Jake Roberson and I talk about Taxi Driver in a recent podcast, actually.) In both movies, we watch the lead character slowly and painfully descend into destructive insanity. But Scorsese held out a form of redemption to his Taxi Driver antihero Travis Bickle (Robert DeNiro, who also plays a critical role in Joker): He can choose to turn his homicidal madness into a political assassination … or save a 12-year-old prostitute (played by Jodie Foster).

No such narrative life vest is thrown to Joker. On one level, of course, it can’t be: We know who Arthur is to become. But while Arthur becomes the villain we expect, his awfulness is rooted in insanity. Much of the real, willful evil we see—the shallow, cruel sins of bullying and indifference—are found in the movie’s other ancillary characters. And so, by extension, we must grapple with the fact that they’re in us, too.

Most of us don’t struggle with the sort of illness that Arthur did. But I think most of us are guilty of de-humanizing people around us. We have such a capacity for compassion and generosity, but so often we mock or, more often, simply turn away. I’m as guilty as anyone. I’ve made fun of people, from the playground to print, when I shouldn’t have. I ignore people when I should look them in the eye. We forget to love the unlovable among us—just like God loved unlovable us.

That’s the truly frightening thing about evil: We don’t need the devil to make us do bad things. We do them just fine by ourselves. We excuse our behavior or don’t even think about it. But the little sins we commit against each other take their toll. Little sins can add up to unimaginable horror.

Joker shows us horror. It gives us yet another origin story for one of America’s best worst villains. But it also holds up a mirror to society—to us—and suggests that, in a world filled with monsters, we bear a bit of responsibility for making them.