The summer blockbuster movie season is here, and Hollywood’s “biggest” films are making their way to theaters.

But after you’ve gotten your fill of Fall Guys and power-hungry apes and, this weekend, imaginary friends, you might want to check out something on a smaller scale: The poignant, powerful We Grown Now.

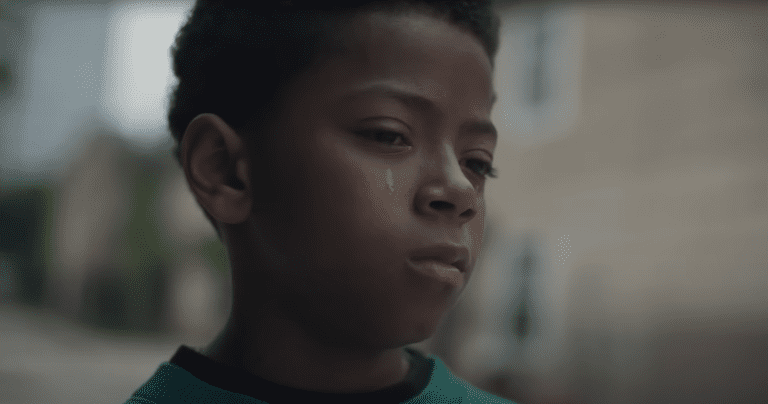

The film, directed by Minhal Baig and distributed by Sony Pictures Classics, focuses on two kids—Malik and Eric—growing up in Chicago’s Cabrini-Green housing project, circa 1992. Seen through their eyes, Cabrini-Green isn’t just the notorious housing complex heard about on the news, awash in drugs and guns and crime. It’s home—but it’s not the home that their parents hoped to give them.

The film has plenty to recommend it. The film is really about the nature of home—what it is and isn’t. It’s about family and society and history. But it’s also about faith, and perhaps how that faith filters into all those other elements.

Malik’s mother, Dolores (played by Jurnee Smollett), raises Malik (Blake Cameron James) and his sister to be Christian. They, along with grandmother Anita (S. Epatha Merkerson), pray together, and you get the sense that those beliefs percolate through their shared lives—so much so that they barely notice it. That faith helps bring a certain warmth to their small home in Cabrini, a warmth visually illustrated by their grandmother’s honey-colored curtains. Sure, that warmth is made of more than just Christianity. But it forms an important cornerstone in this tight-knit family.

Eric’s father (Lil Rel Howery) loves his boy, too. But Eric’s home—which the movie paints in harsher, cooler colors—lacks the familial magic that Malik enjoys. And while we don’t see much of Eric’s home life, religion seems to play a scant role there (if it plays a role at all).

Eric (Gian Knight Ramirez) and Malik have a lot in common. But through faith, we begin to see their differences, too.

‘What Is All This For?’

In October 1992, a stray bullet killed 7-year-old Dantrell Davis in Cabrini-Green. The death shook both the community and the wider city of Chicago: The mayor vowed to clean up Cabrini (using some frightening heavy-handed tactics to do so). Dolores worried ever more about her son’s safety. And Malik and Eric tried to make sense of the young boy’s death.

After Dantrell’s funeral, the two boys sit on some church steps and talk.

“He’s in a better place now,” Malik says.

“I don’t know,” Eric says. “I think he just … go.”

Eric admits that he believes that Jesus lived, but he suspects that the Nazarene was just a man—and He’s not coming back. He suspects that the afterlife isn’t real—that Dantrell just died and that’s that. No heavenly reward. No deeper meaning.

Malik pushes back. “If there ain’t no afterlife, what is all this for?” he asks.

Malik holds out hope that all the suffering that he sees does have a place in a greater story. That what happens today does matter for tomorrow. And we realize that Malik’s hope, and Eric’s doubt, are shaping their own trajectories within Cabrini, too.

The day that Dantrell died, the two boys are approached by an older kid, inviting them both to try on a diamond-studded watch. “I’m good, Malik says, and walks away—knowing the watch comes from drug money. But Eric tries it on. “What does it matter?” He later tells Malik. “Money is money.”

Later, the two boys ditch school and go to Chicago’s famous Art Institute, where they examine Walter Ellison’s 1935 painting “Train Station.” The painting depicts the Great Migration, when African Americans moved from the hostile South to cities like Chicago. Ellison painted a Black porter carting around luggage for some obviously wealthy white travelers—a depiction that Malik bristles at. “They can carry their own bags!” Malik says.

“They get paid to do it,” Eric says.

Trying to Fly

After the funeral, Malik asked what’s all this for? There’s got to be a reason. A purpose. It matters whether he tries on that watch. It matters that this guy in the painting is stuck carrying luggage. It matters that Dantrell died. These injustices matter because there’s such a thing as justice.

But Eric’s not so sure. Maybe we don’t get an afterlife. Maybe we don’t have purpose. Maybe justice? No such thing. So why not get what we can now? And does it really matter how we get it?

The movie hints at the boys’ different trajectories at its very outset—when the two drag a discarded mattress out to the playground. They throw it on a pile of other mattresses and take turns jumping on them: Malik is the undisputed king of this playground game—and after he marvels at how well he jumped today. “That was the closest I got to God!” he says.

Try as he might, Eric can’t quite soar like Malik. His feet are rooted too deeply in this world to go flying into another.

By the time the movie heads into the final act, we understand that the two best friends are on two different paths. Without giving anything away, we feel that Malik might jump beyond his Cabrini childhood—fly into a wider world beyond. Eric, we worry, may simply get stuck there, trapped in its poverty and vices.

But the film offers some hope for Eric—and again, it comes back to faith. With his friendship with Malik threatened by circumstance and change and schoolboy pride, Eric pays a visit to Malik’s family. And when Dolores says that Malik can’t see him, Eric still hovers in the doorway.

“Can we pray together?” he asks Dolores.

And so Eric, Dolores and grandma Anita gather together and pray. “Heavenly father, watch over us, your children,” Dolores says. “Grand that we mend all that is broken.”

We find a lot of brokenness in We Grown Now. But we find a lot of healing, too—and that healing is powered by faith as much as anything. And that’s one of many reasons why this film is so worth seeing.