The movie Sight came out a couple of weeks ago. It was released alongside the more heralded Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga and The Garfield Movie. Directed by Andrew Hyatt and coming with a subtle-but-powerful foundation of faith, Sight, based on a true story, is a gently inspiring, smartly crafted film.

And honestly, it has stuck with me longer than I expected—thanks to Flannery O’Conner.

Sight’s narrative come in two parts: One focused on a young, bright aspiring doctor named Ming Wang (played by Ben Wang), coming of age in China during the Cultural Revolution. The other introduced us to a mature Dr. Wang (Terry Chen)—now one of the world’s most renowned eye surgeons. And in the movie, he’s faced with one of the most difficult challenges of his professional life.

A young girl from India—her name’s Kajal (Mia Swami Nathan)—is brought to Wang by a kindly nun, Sister Marie (Fionnula Flanagan). Kajal is blind, of course; knowing that truly blind beggars make more in the Indian slums than those just faking it, Kajal’s stepmother poured acid into the little girl’s eyes.

Wang—a doctor quite confident of his abilities and a bit hungry for fawning press pieces—sizes up Kajal’s case and nearly turns her away. Even with Wang’s considerable skill, he knows that there’s only a small chance that Kajal’s sight will return. But Sister Marie convinces him to treat Kajal. “She has traveled across the world for a chance,” she tells him. “Even a slim chance.”

The rest of the film weaves Wang’s backstory with this more modern medical drama. And—in an interesting choice by Hyatt—it steers clear of overt spirituality for most of its runtime. The younger Wang knew nothing of Christianity. And when he’s older, everyone calls him the miracle worker: He doesn’t need any help from God, thanks all the same.

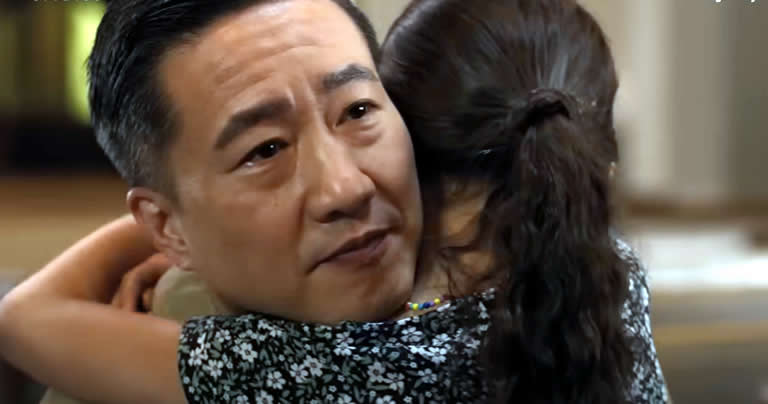

But as Wang works to restore Kajal’s eyesight—and in the aftermath—Wang discovers that, whether blind or no, the little girl “sees” better than Wang himself. The child loves God—and she loves others with pure delight. Ultimately, she gives Wang a rosary and tells him that she’ll be praying for him. And Wang, touched, realizes he needs that prayer.

Blinded, In Spite of the Light

While the real Dr. Ming Wang is a committed Christian, the one we see onscreen seems puzzled, and perhaps slightly amazed, when confronted with Kajal’s childlike faith. He grapples with the upside-down universe of God. How weakness can be strength. How affliction can come with joy. How a world-renowned doctor can feel small next to a 6-year-old girl.

I sometimes wonder how many Christians really understand that. I wonder if I do.

I work for a Christian entertainment outlet for a Christian ministry, and I love my job. We tell our readers, the majority of whom are parents looking for appropriate entertainment for their kids, what to watch out for. Does this movie have profanity? Does that one have any sex scenes? What about the violence? Is that too extreme?

I’m going to see a movie tonight, in fact, and I’ll be dutifully recording all the “negative content” that I see. And again, I know that readers will appreciate it. I’m certainly not saving anyone’s eyesight. But for the families that read our reviews, we are providing a service that they think is important. And I think it’s important, too.

But God loves His paradoxes. And as I wait for this movie, I’m reading Flannery O’Connor: Spiritual Writings, edited by Robert Ellsberg. I’ve read a lot of O’Connor’s work before movie screenings, and I’m keenly aware that many—most—of her stories would be filled with what I’d term in my reviews “negative content.”

And here’s the kicker: O’Connor was a deeply committed Christian—a writer for whom themes of sin and grace and redemption and God seemingly permeates every novel, every short story, every letter. Her work hits me in a way that few Christian movies do.

And so much of her work is populated by characters who think they’re so good—the apple of God’s eye and ever-so-much better than their neighbors or servants or relatives. Often they’re rocked by cataclysm that forces them to see the nature of God more clearly. And perhaps still, in the end, run from that beautiful, terrible, awe-ful sight.

Hard Stories

In a 1955 letter, O’Connor writes:

I am mighty tired of reading reviews that call A Good Man [Is Hard to Find, a collection of short stories] brutal and sarcastic. The stories are hard but they are hard because there is nothing harder or less sentimental than Christian realism. I believe that there are many rough beasts slouching toward Bethlehem to be born and I have reported on the progress of a few of them, and when I see these stories described as horror stories I am always amused because the reviewer always has hold of the wrong horror.

I think a lot of Christians like “nice” stories. Stories that don’t have huge issues. Stories you can watch with your family. Stories that confirm, rather than challenge, what you think and feel and believe.

And there’s nothing wrong with nice. Nice is a warm blanket by the fire. Nice is a well-kept English garden. Nice is a sweet, inoffensive movie to enjoy for a couple of hours that Christian reviewers like me can approve of.

Nice is being a doctor who can do things that few other doctors can and be praised and paid for it.

But nice can be a trap, too. The world, often, isn’t nice, as Dr. Wang himself knew all too well growing up. And it’s that world, more than the world of pretty pictures and cozy comforts, where we see God best. God goes places we’re scared to go. And sometimes, He pushes in directions we’d rather not turn. Our God is one of both comfort and cataclysm—with us in both sickness and health. As O’Connor, who suffered and died from lupus at the age of 39, knew full well.

In the movie Sight, Dr. Wang works relentlessly to bring Kajal’s own sight back. To take away that burden of blindness, Wang believes, would mean success. Victory. Wouldn’t that be … nice?

Yes. Yes it would. Both Kajal and Sister Marie would love for that sight to be returned. But they understand that our God is one for whom success and victory looks very different. We can find beauty—sometimes hard, painful beauty—when we go beyond the nice. It’s funny, because I’d classify Sight as a pretty nice movie: It’s not filled with language. The violence we see is fairly understated compared to what it could be. And yet, when we really think the characters here, we find a certain ferocious grace.

At one point, Sister Marie reminds Dr. Wang that the miracle isn’t Kajal’s eyesight returning. The miracle is in front of Wang’s own eyes—Kajal herself. “Look at what God uses when we refuse to believe there is no purpose,” she says. “[Kajal] has moved beyond the tragedy of the past and embraces the present with happiness and joy and love.”

Kajal, in short, could be a hero in one of Flannery O’Connor’s stories.

Me? I’m not so sure.