(1) For those who don’t know the play, here’s a brief introduction:

(a) Twins (Sebastian and Viola) shipwrecked, separated (each thinks the other has drowned); both come on the shores of Illyria but neither runs into the other; Viola dresses as her brother (and passes as a man) for protection; goes into service with Duke Orsino

(b) Duke Orsino is in love with Countess Olivia, who won’t give him the time of day

(c) Olivia is mourning her brother – though there’s evidence she’s overdoing it for effect or for emotional self-indulgence

(d) Olivia employs a steward to run her estate – his name is Malvolio, and he keeps having run ins with her uncle, Sir Toby Belch and his friend, Sir Andrew Aguecheek. Both of these are down on their luck “gentlemen,” who are sponging off of her

(2) There are lots of themes in this play—love (obviously), the enjoyment of life vs. a sort of stern negative attitude toward pleasure. But I think Shakespeare takes a sort of even handed (or let’s say appropriately complicated) approach, that it’s possible to go too far either direction (drunken parties vs. being a control freak trying to make other people be virtuous).

Other themes: music; madness; illusion vs. reality; family (the reunion of Viola and Sebastian can be incredibly moving: a kind of resurrection)

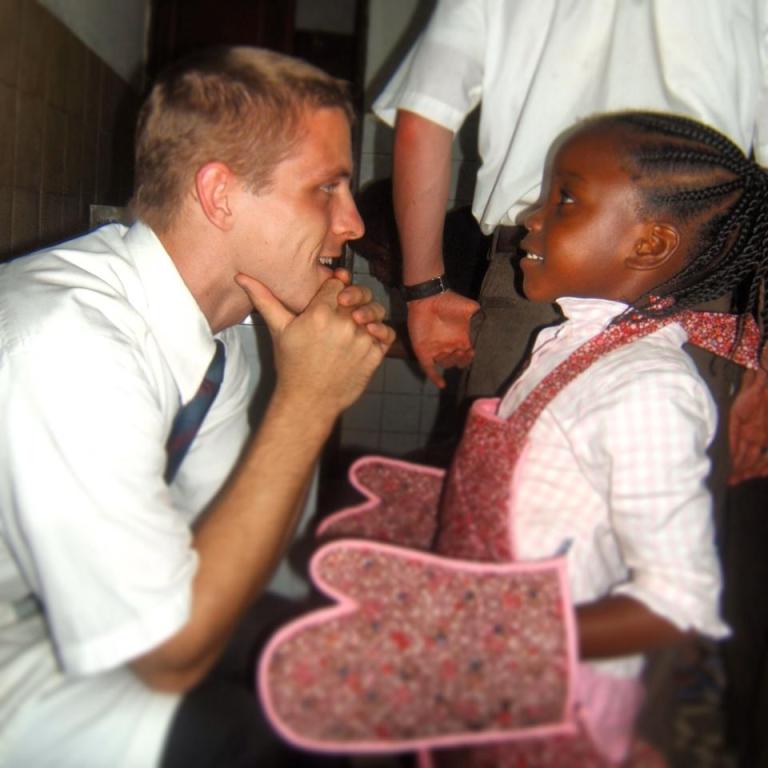

And this production is doing a lot with identity and diversity (including identity and diversity based on gender and ethnicity and cul ture)

ture)

(3) But I want to focus on one theme: love and self-deception [I think you’ll see that it relates to some of the other themes and to the things this particular production is doing]

I want to start with something C. S. Lewis once wrote:

“The most precious gift that marriage gave me was the constant impact of something very close and intimate, yet all the time unmistakably other, resistant – in a word, real.” (A Grief Observed 18-19)

He goes on to say: “All reality is iconoclastic.” (“Iconoclasm” literally means “the breaking of images.”) That is, we form images in our minds, including images of other people. But reality breaks up the images. Lewis again: “The earthly beloved, even in this life, incessantly triumphs over your mere idea of her. And you want her to; you want her with all her resistances, all her faults, all her unexpectedness. That is, in her foursquare and independent reality. And this, not any image or memory, is what we are to love . . .”

And so: One of the great gifts of love is the way it gives us access to someone absolutely other than ourselves.

Yet as Twelfth Night shows, love–or at least what we call “love”–can also be an instrument of self-deception. “Love”–or those emotions we associate with romantic love—tempts us to create an idealized version of the person we think we’re in love with, a version that may have little to do with the actual person. The image gets in the way, even when we are with the person. Which leads to the question:

Do we see what is right in front of us? Do we see, do we really see, the other person? Or do we create an imaginary substitute for the other person and fall in love with that?

That is one of the important questions posed by the play. Let me give you several examples, and we’ll see how they play out.

(a) The very first lines of the play are:

If music be the food of love, play on.

Give me excess of it, that, surfeiting,

The appetite may sicken and so die.

That strain again! It had a dying fall.

O, it came o’er my ear like the sweet sound

That breathes upon a bank of violets,

Stealing and giving odor.

This is Duke Orsino—basically he’s saying, music stirs feelings of romantic love, and because love is unsatisfying and even tormenting, play music so as to give me emotional excess, so that I’ll get so sick of it, and the emotions will die. In other words, he loves the feelings in a way, but also is sick of them—they are both pleasurable and painful. Then he says:

Enough; no more. [this is about the music}

’Tis not so sweet now as it was before.

[Then he comments on the “spirit of love” and how it devours everything in its path. . . . and then finally he says:]

So full of shapes is fancy

That it alone is high fantastical.

“Fancy” is a word that meant both love and imagination; basically he says that love is the most imaginative thing in the world—which sounds great unless you realize that what he is saying is that love is especially good at creating imaginary things that are not really there. In other words, along with many other uses, it can be an instrument for self-deception.

We soon learn that his love for Olivia is just this sort of imaginary love: she doesn’t care for him, and he is more in love with an imaginary version of her—or even with his own feelings—than with her herself.

(b) But Olivia turns out to have the same problem: She has vowed not to love because she is mourning for her brother. But Orsino sends Viola as a messenger to carry his message of pining love to Olivia. (Remember that Viola is dressed as a man.)

Viola does a good job (though it’s done with humor too—after she gives her first speech, she says to Olivia in effect: are you really Olivia, because if you’re not, I don’t want to waste my speech on you. Notice again that the speech is first given without knowing whether it’s being directed to the right person: there’s a disconnect between love and the reality of the person who is supposedly loved.)

Anyway, Olivia – contrary to her vow not to love – falls in love with Viola, thinking her to be a man. Again, this is a kind of imaginary love that has little to do with the person in front of her:

This self-deception about love leads to all sorts of confusion, much of it very funny: but eventually Olivia does get married – not to Viola, but to someone who looks just like her, or almost just like her. (Spoiler alert.) The point is that Olivia’s love was never for an actual person, but for an appearance: we can only hope that a truer, deeper kind of love can blossom at some point.

(c) Let’s go to another example: I mentioned Malvolio, Olivia’s steward. He seems to be stern and self-denying. But he too is susceptible to love, at least love of this emotional, imaginary variety that has little to do with the actual person.

Sir Toby Belch and Andrew Aguecheek (you may remember) don’t care for Malvolio, so they (along with one of Olivia’s servants named Maria) cook up a scheme to make Malvolio think that Olivia is in love with him. He falls for the scheme with an ease that makes it obvious he really wants to believe it’s true.

In fact at one point he takes a cryptic line from the letter Olivia has supposedly written (MOAI doth sway my life) and tries to make it fit himself: “This simulation is not as the former, and yet to crush this a little, it would bow to me, for every one of these letters are in my name.”

You’ll see what he does in response to the letter. (It’s really funny.)

Shakespeare is using Malvolio to show the dangers of self-deception – in this case, self-deception that springs from ego and a craving to be love—and Shakespeare is maybe also having us enjoy seeing Malvolio get fooled and punished.

But pay attention – and I think you’ll see that the play suggests the joke on Malvolio goes too far and ends up being cruel. Olivia expresses her sympathy for Malvolio and the value she puts on his work as her steward. She even says, “He hath been most notoriously abused.”

(d) One final example, which actually involves Duke Orsino again. Remember that Viola is working for him – but dressed as a man. In other words, Orsino literally does not see who is really in front of him—or doesn’t see some important things about her, especially that she is a woman.

That results in some interesting and humorous tension as Viola pretty clearly falls in love with Orsino, and as Orsino continues to be oblivious to her interest in him. They have fascinating discussions about the nature of love, and about the nature of men and women – with the main result being (in my opinion) that we see that Orsino still has a lot to learn on both subjects.

But what makes their relationship really compelling, I think, is that it maybe shows us something about what really should be the foundation of love, including romantic love

Not a pleasurably painful indulgence in emotion

Not merely physically attraction

And certainly not falling in love with an imaginary version of the other person

But something like . . . I don’t know . . . friendship?

It appears that Viola and Orsino actually come to have an appreciation for each other, partly, or even mainly, because Orsino doesn’t know that she’s a woman. (With women he seems unable to respond with anything but emotional and imaginative self-indulence.) Rather than indulging in imaginary love, Orsino sees her as a companion and a friend. And so when he finally finds out she’s a woman, it’s as if he realizes . . .

Wow, I could actually be in love with somebody I know and like.

The closing lines of the play are interesting: Orsino says to Viola that, once she has changed into women’s clothing, she will be “Orsino’s mistress and his fancy’s queen.”

The meaning of that line may not be entirely clear because we don’t use “mistress” or “fancy” in the same way. “Mistress” here means “ruler” (as the feminine version of “master”): In other words, I will be your servant and will be ruled by you. And “fancy” (remember) means love but also imagination: so rather than “fancy” being in charge (as it was in Orsino’s first speech), now the other person (Viola) will be the queen, the ruler, of his “fancy,” his emotions and his imagination, rather than the other way around.

It’s at least a step in the right direction.

(4) One last thing I’d like to do with the theme if there’s time:

The reunion of Viola and her brother (Sebastian) is interesting because they are twins, and neither thinks the other is alive: so it’s as if they are resurrected to each other. But they also wonder if the other person is real, or if the other person is just a projection or mirror image of themselves. (The phenomenon of twins raises interesting questions about identity: who am I if there is someone else who looks like me.)

They go through quite a process to determine: are you real?

They want to make sure the other person is really other, is really someone else, and that they’re seeing them for who they really are.

It’s one more comment on the question: Do you see what is right in front of you? Do you really see the other person?

As I noted, It also raises questions about identity: Am I really the person I think I am? And that in turn leads to questions about diversity. When I see people who are obviously different from me—in gender, race, or physical appearance—am I so blinded by appearance and by stereotypes that I can’t see the person who is in front of me? When it comes to political and religious differences, am I so sure what the other people or groups of people are like that I don’t see who they really are?

(6) Let me close with some more lines from C. S. Lewis: When his wife died he worried that he would sink back into his self-involvement and self-deception, and he cried out: “Oh God, God, why did you take such trouble to force this creature [meaning himself] out of its shell if it is now doomed to crawl back—to be sucked back—into it?” (19) He was afraid of sinking back into an isolated, self-involved world.

In addition, he didn’t want to fall in love with his memory of his wife, with “an image in [his] own mind” (20).

Just as he wanted to truly love God—not just his idea of God—so he wanted his relationship with his wife to be “Not [with] my idea of [her], but [with] her. Yes, and also not my idea of my neighbor, but my neighbor. For don’t we often make this mistake as regards people who are still alive—who are with us in the same room? Talking and acting not to the man himself but to the picture—almost the precis [that is, the abstract or summary]—[that] we’ve made of him in our own minds? . . .” (67).

How do we avoid that? How do we actually relate to the person who is in front of us? I guess I’d say that that is the task of a lifetime.

As my favorite philosopher (Emmanuel Levinas) put is, we need to welcome the Other (the other person), even when that disturbs our comfort or our complacency. We need to “welcome [the other person’s] expression, in which at each instant [they overflow] the idea a thought [our thought] would carry away from [their expression].” We need to be open to “The way in which the other presents himself, exceeding the idea of the other in me.” We need to be ready to be taught—to learn something we didn’t think we knew.

The production tonight may challenge you in some ways—challenge some of your preconceptions about race or gender or who knows what else. In the spirit of this theme I’ve been talking about (Do you see what’s right in front of you?) I would suggest just being open, ready to experience what you see without trying to package it and label it. If we can do that, we might actually learn something.

Do You See What’s Right in Front of You?: Love and Self-Deception in Twelfth Night

C. S. Lewis once wrote: “The most precious gift that marriage gave me was the constant impact of something very close and intimate, yet all the time unmistakably other, resistant – in a word, real.” One of the great gifts of love is the way it gives us access to someone absolutely other than ourselves. Yet as Twelfth Night shows, love–or at least what we call “love”–can also be an instrument of self-deception. Do we see what is right in front of us? Do we see the other person? Or do we create an imaginary substitute for the other person and fall in love with that?

That kind of self-deception touches on many aspects of our lives, including personal identity, diversity, and social and political conflict. Am I really the person I think I am? When I see people who are obviously different from me–in gender, race, or physical appearance–am I so blinded by appearance and by stereotypes that I can’t see the person who is in front of me? When it comes to political and religious differences, am I so sure what the other people or groups of people are like that I don’t see who they really are?

Twelfth Night confronts us with such issues. Two of the main characters are twins, and one of them disguises herself as her brother. One result is that Countess Olivia thinks she’s in love with the sister but ends up marrying the brother. Another is that Duke Orsino doesn’t realize he is coming to love the sister because he thinks she’s a man. One of the main plot lines of the play is Orsino’s education in learning to see what is in front of him. Other characters play on the human tendency to self-deception by getting Malvolio–Olivia’s capable but annoying steward–to think Olivia is in love with him. The multiple cases of confusion are delightfully entertaining, but they also raise the question of whether we actually see the people in front of us. And if we don’t, how in the world can we truly enter into loving relationships with them?

By adding elements of cultural and racial difference, this production highlights some of the issues already present in the play: identity, what it means to love, and the question of whether we can really see what is in front of us.