Sociologist Robert Wuthnow observed some years ago that American Protestants are increasingly alienated from denominational structures. In a useful set of distinctions that may say more about the perception of self and of others, than it does about social realities, Wuthnow explained that the vast majority of American church-goers consider themselves as residents of America’s Main Street: A cohort of people who, by and large, occupy the middle of the country, who are of relatively modest means and for whom the issues of faith are largely lived out in specific and local terms. By contrast, Wuthnow notes that denominations are governed by people who think of themselves (or are perceived) as financial and cultural elites, people who occupy (respectively) Wall Street and Main Street. Socially, they tend to belong to positions of greater wealth and wield greater influence. They also tend to think of church life as one shaped by national mandates of one kind or another. Wuthnow goes onto note that, given the difference in perspective, the residents of Main Street instinctively mistrust the residents of Wall Street and High Street, and – for that reason – they express their alienation from those centers of power in the only ways left to them: disaffection, disinterest and hostility.

Sociologist Robert Wuthnow observed some years ago that American Protestants are increasingly alienated from denominational structures. In a useful set of distinctions that may say more about the perception of self and of others, than it does about social realities, Wuthnow explained that the vast majority of American church-goers consider themselves as residents of America’s Main Street: A cohort of people who, by and large, occupy the middle of the country, who are of relatively modest means and for whom the issues of faith are largely lived out in specific and local terms. By contrast, Wuthnow notes that denominations are governed by people who think of themselves (or are perceived) as financial and cultural elites, people who occupy (respectively) Wall Street and Main Street. Socially, they tend to belong to positions of greater wealth and wield greater influence. They also tend to think of church life as one shaped by national mandates of one kind or another. Wuthnow goes onto note that, given the difference in perspective, the residents of Main Street instinctively mistrust the residents of Wall Street and High Street, and – for that reason – they express their alienation from those centers of power in the only ways left to them: disaffection, disinterest and hostility.

Whether this is, in fact, demographically true in a hard, objective sense is – in some ways – irrelevant. Like most perceptions, it is infinitely more powerful than any data that may be brought to bear on the conversation.

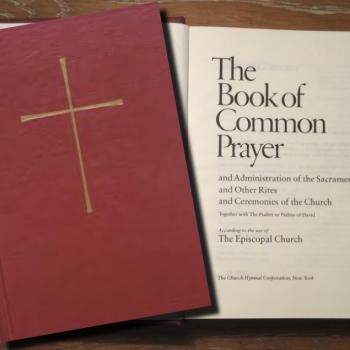

It is also true that the lengthy and complex nature of mainline Protestantism’s denominational conventions or conferences has also created a “governing class” (as one Episcopal priest puts it) that makes decisions for the rest of the church on a regular basis. Take, for example, The Episcopal Church. Meeting in Austin this week, the Convention is effectively twelve days long. Only people who can treat it as a part of their job (ordained delegates and Bishops for example) or people who have extraordinary resources and / or are retired can really entertain making that kind of commitment. And, in fact, a significant number of those who do attend are frequenters of the church’s General Convention.

In a culture in which commitment to local congregations — never mind national bodies is increasingly fragile and in a financial environment in which local congregations struggle to survive — it is time to consider revising our approach to decision-making of this kind. It is unwieldy, unrepresentative and yet it makes sweeping commitments on behalf of the entire church. Worst of all, perhaps, conventions of this kind lack any mechanism for prayerful discernment or theological conversation.

This is not to denigrate the communal or corporate identity of the church or its ecclesiological significance. Rather, rethinking our approach to governance is a matter of re-capturing theological perspective and spiritual balance. The Episcopal Church is named what it is because the word, “Episcopal” recognizes the importance of bishops and the significance of their office, as a symbol of the church’s unity. But historically the office of bishop was grounded in profound convictions of a theological and pastoral nature. The title, episcopos, which means “overseer” or “guardian” and even the symbols of that office suggest responsibility for the church and its members, not for the denomination and its bureaucracy.

It is not surprising, then, that Ignatius of Antioch – who was, perhaps, the most influential voice in the early church concerning the nature of the episcopacy – relied on the images of athlete, anvil, sailor and harbor to describe the work of a bishop. The first two images invoke notions of self-discipline, submission and availability. The third and fourth are images of care and protection. Together, as Kevin Clarke observes, Ignatius emphasizes the responsibility of the bishop to be available as the one through whom the people of God are “bishoped by Christ.”

Hence, Ignatius tells his fellow bishop, Polycarp:

Do justice to your office with constant care for both physical and spiritual concerns. Focus on unity, for there is nothing better. Bear with all people, even as the Lord bears with you; endure all in love, just as you now do. Devote yourself to unceasing prayers; ask for greater understanding than you have. Keep alert with an unresting spirit. Speak to the people individually, in accordance with God’s example. Bear the diseases of all, as a perfect athlete. (Polycarp 1.2-3)

It is this ethos and not the prevailing bureaucratic and legislative culture of national conventions that should shape our collective life. What will it look like to abandon our current structure? I am not sure and, judging from the evidence available from Austin thus far, it is the bureaucratic ethos that will continue to dominate for the foreseeable future. But that ethos is not serving the church well.