Prosper of Aquitaine, a disciple of St. Augustine in the church’s early efforts to clarify its faith coined a phrase in Latin that is often condensed and reads, lex orandi, lex credendi. Loosely translated the Latin (it is often said) means, “the law of praying is the law of believing” or – to put it more directly, “prayer leads to belief or shapes theology.” Like many, while I believe that motto to be true, I also believe that there is good reason to believe that Prosper was thinking in particular of the Eucharist or Communion, which – properly understood – is also a prayer.

Prosper of Aquitaine, a disciple of St. Augustine in the church’s early efforts to clarify its faith coined a phrase in Latin that is often condensed and reads, lex orandi, lex credendi. Loosely translated the Latin (it is often said) means, “the law of praying is the law of believing” or – to put it more directly, “prayer leads to belief or shapes theology.” Like many, while I believe that motto to be true, I also believe that there is good reason to believe that Prosper was thinking in particular of the Eucharist or Communion, which – properly understood – is also a prayer.

That being true, I think it is important that we learn from praying the Eucharist and that we let those prayers shape our theology. And, by inference, that also means that there should be a high degree of congruence between the prayers we say in the Eucharist and what we make of the Eucharist itself. For that reason, I frequently find myself focusing on the Eucharist phrase by phrase, moment by moment when I celebrate or receive the Eucharist on any given Sunday.

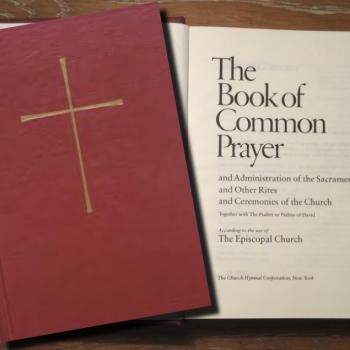

That practice has led me to pay particular attention to the prayers that appear at the end of our praying, that is, the postcommunion prayer, because that prayer looks back over what we have experienced and captures God’s purpose in having made this experience available to us. In my tradition, there are multiple versions of that prayer, some in traditional language and some in more contemporary language. Two versions appear below:

Almighty and everliving God, we most heartily thank thee

for that thou dost feed us, in these holy mysteries, with the

spiritual food of the most precious Body and Blood of thy

Son our Savior Jesus Christ; and dost assure us thereby of

thy favor and goodness towards us; and that we are very

members incorporate in the mystical body of thy Son, the

blessed company of all faithful people; and are also heirs,

through hope, of thy everlasting kingdom. And we humbly

beseech thee, O heavenly Father, so to assist us with thy

grace, that we may continue in that holy fellowship, and do

all such good works as thou hast prepared for us to walk in;

through Jesus Christ our Lord, to whom with thee and the

Holy Ghost, be all honor and glory, world without end.

Amen.Almighty and everliving God,

we thank you for feeding us with the spiritual food

of the most precious Body and Blood

of your Son our Savior Jesus Christ;

and for assuring us in these holy mysteries

that we are living members of the Body of your Son,

and heirs of your eternal kingdom.

And now, Father, send us out

to do the work you have given us to do,

to love and serve you

as faithful witnesses of Christ our Lord.

To him, to you, and to the Holy Spirit,

be honor and glory, now and for ever. Amen.

For all the subtle differences between the versions of the postcommunion prayer, there are two assumptions that both prayers make:

One, in the body and blood of Christ the recipients are in-corporated or made a part of the body of Christ. This affirmation is based upon the most important assumption that Christians make about the Eucharist and about the members – or one might say, the body parts — of Christ’s church.

The Eucharist deepens the Christian’s journey into God in Christ. The Christian, meal by meal, participates more in the body of Christ. And the Eucharist is the means by which that lifelong journey takes shape.

Two, the experience of the Eucharist strengthens the church in its responsibility for the work that God has given the church to do, which includes love, service and witness to the One who makes that work possible.

Following Prosper’s motto, attention to those two assumptions tells us something about what we can hope to derive from our experience of the Eucharist. But they also tell us something about the Eucharist itself: It is a sacrament for those who have been baptized. It is predicated on a very specific set of assumptions of what was accomplished on the cross on our behalf, and it is meant to deepen the Christian’s availability to the purposes of God’s Kingdom.

On this reading of things, then, it makes sense to say that the Eucharist is open to “all who are baptized,” but it does not make sense to say that the Eucharist is an act of hospitality or a gesture of love or to welcome anyone and everyone, baptized or not.

In fact, the postcommunion prayer and much of the rest of the Eucharistic rite’s language puts the non-Christian in the peculiar position of receiving communion and giving thanks for it in words that any honest non-Christian would find strange, if not hypocritical to affirm.

Peculiar, that is, only if one ignores Prosper’s motto.

That is why we offer people the opportunity to receive a blessing, if they are not baptized, and that is why we make it clear that those who not baptized are welcome to worship with us, even though we don’t encourage them to receive the Eucharist.

As we consider how we might revise any future prayerbook, it is worth keeping Prosper’s advice in mind. To ignore it threatens to diminish both our worship and our theology.