I’m going to do something really dangerous. I’m going to summarize one of history’s greatest pieces of literature in just few, scant sentences: The Book of Job.

Movement One: We are introduced to Job in a wager between God and an angelic provocateur. That movement is designed to let us peak behind the curtain, underlining Job’s innocence.

Movement Two: Job’s life goes to proverbial “hell in a hand basket,” underlining the fact that bad things happen to good people.

Movement Three: Job’s friends arrive to “comfort” him, but what they try to do, in fact, is to comfort themselves. They do that by arguing that there has to be an explanation for Job’s misfortunes and Job is probably to blame – a claim that is falsified by Movement One.

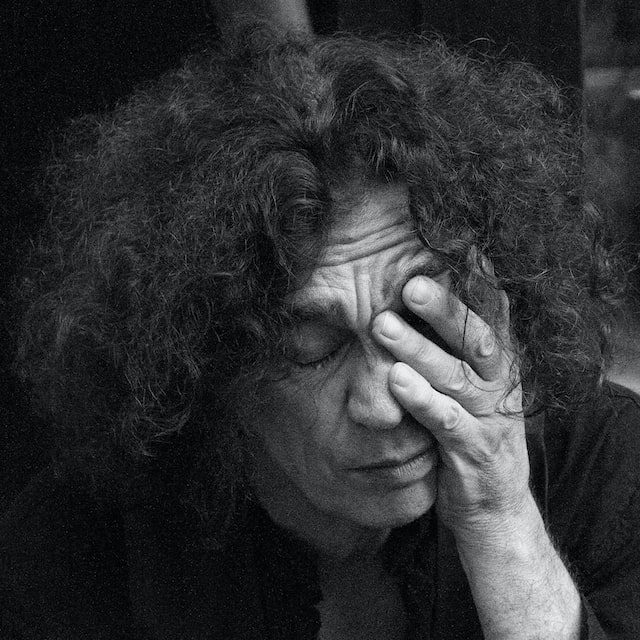

Movement Four: In his misery, Job finally takes God to task. In response, God points out that Job is out of his depth and Job concedes, pledging his faith in spite of his circumstances.

Movement Five: In an epilogue, Job’s health, wealth, and family are restored.

In a world of things one might learn from pondering The Book of Job, there are a handful of things to remember:

This is a fictional story. It is not a biography.

There are many kinds of truth in the Bible, and some of them rely on historical fact. The life and ministry of Jesus and the Resurrection are good examples. The “truth” offered by The Book of Job does not.

The next thing to note is that The Book of Job does not offer a window into how God functions behind the scenes.

In fact, Movement Four (above) explicitly denies that we can know why things happen the way that they do. This is particularly important when it comes to Movement One: God does not have coffee with Satan and discuss offering up one of his most faithful followers for an experiment. Movement One is an artifice, a literary device, designed to falsify the statements of Job’s so-called comforters before they even begin sharing their words of “wisdom.”

By beginning his story this way the writer is taking aim at the explanations that Job’s friends are offering and, in particular, the notion that “good things happen to God-fearing people” and “bad things happen to people who are not.”

It has been said that Job’s friends are advocates of what scholars describe as the “Deuteronomic principle” – i.e., a notion derived from the Book of Deuteronomy that the fortunes people experience vary with their faithfulness. But this is probably unfair to the Book of Deuteronomy.

Yes, Deuteronomy suggests that, on balance, faithfulness to the Covenant offers the hope of a better outcome than rebellion against God. But we all use this kind of language when we commend a way of behaving. For example, a parent might say to a child who is getting dangerously close to breaking a window, “Good boys don’t throw stones.” But boys still do and – if a parent reflected deeply on it – they would grant that stone-throwing isn’t definitive of human character. There are also a lot of cases in which throwing a stone doesn’t harm someone else or risk breaking a window. Skipping stones on the water, for example, is a harmless game. But we use this kind of language to encourage certain kinds of behavior.

That said, from time immemorial, there have been people who misread such language and turn it into a principle. That is the kind of flat-footed literalism that led some people to assume that what the Book of Deuteronomy promises is that good things happen to people who keep God’s covenant and bad things happen to those who don’t. The author of Job is calling that assumption into question.

Of course, having made this point, the question arises: “Well, then it doesn’t really matter what I do, does it?”

To which the writer answers, “Yes. It does.” And the author underlines this point by picturing Job taking God to court, insisting on an explanation. God refuses to offer an explanation and notes that Job is asking questions far beyond his paygrade. Modeling the kind of behavior that the author believes should characterize our lives when we encounter suffering, Job affirms his faith in God and in God’s ability to achieve his purposes, and then pledges his own continued obedience.

Finally, there is this to note: The epilogue may well be a later addition to The Book of Job, but if it was, it was added early enough that it is impossible to know for sure.

Given the point that the author is making, it would make sense to leave Job in sackcloth. His point is not that there is a quid pro quo for faithfulness: Hang in there and you will get your stuff back. It is also kind of a peculiar resolution. After all, Job’s first family isn’t restored to Job. So, it sucks to be Mrs. Job #1.

My guess, then, along with other scholars, is that the epilogue is an addition that was made because the point the writer is making is hard to take. Down through the ages there has been and continues to be a powerful temptation to treat our faith in God as a “Get out of Jail Free” card.

The message of Job, like the message of the Gospel, is very different. It is a way of life in a troubled world. Not a way out of trouble.

If I can do something really dangerous, one last time, and oversimplify a great piece of literature: the message of Job in (way) less than 140 characters is this:

“Bad things happen to faithful people. Be faithful anyway.”

Photo by Emmanuel Phaeton on Unsplash