A recent article on conversations between the deans of Episcopal seminaries and others got me thinking about seminaries and about the future of mainline churches. The article itself was a fairly poor introduction to what actually transpired in those meetings. My online conversation about the article revealed, for example, that there were sitting deans involved in the meeting. So, I’m prepared to hope that the conversations were better focused than the article suggested.

Based on what the article did say, the conversation was about “flexibility for admission to the MDiv, lowering barriers for discernment to holy orders, recruitment of candidates from diverse backgrounds.” Exactly what this means is hard to say but this much is clear: (1) “Flexibility” and (2) “lowering barriers [standards?]” are not the reason for shrinking seminary enrollment. The real problems are these:

I wish the leaders of what is left of our seminaries all the best in navigating the challenges that lie ahead. But, frankly, I think the seminaries would be best served by a robust, exacting focus on the core theological preparation; the needs of parishes; the ministries that support the growth of the local parish; and the preparation of 21st century clergy, who are equipped to lead congregations through the complex challenges that lie ahead. That means bringing the essentials of theological education to bear on dealing with social media; complex intergenerational dynamics; a spiritually grounded, but hard-headed acquaintance with the finances of the modern church; and a renewed emphasis on the sacramental and teaching offices of the church.

That preparation cannot be beholden to a bye-gone day and age. It cannot be beholden to the interests of the academy; and it cannot be enthralled to politics under an ecclesial guise. The seminaries are not going to find the solution in either looking for unanimity at the denominational level or reinvention of the seminary curriculum driven by their own institutional priorities. The rebranding of seminary education that has dominated the news as one seminary after another has failed does not fool anyone. The ones that will survive will look to the needs of clergy, not euphemisms for decline.

To coin the popular phrase, “It’s about the congregation, stupid.” And this should be the call to action, not just for the seminaries but for parish priests, bishops and denominational leaders.

Our parish has been blessed with a steady and extraordinary number of new members, including young families. We are grateful. But, candidly, it doesn’t have anything to do with our denominational ties. Unless they were already Episcopalians, our newest members know little about TEC. Come to that, a number of those who already were Episcopalians don’t know much about the church’s history, theological distinctives, or liturgy.

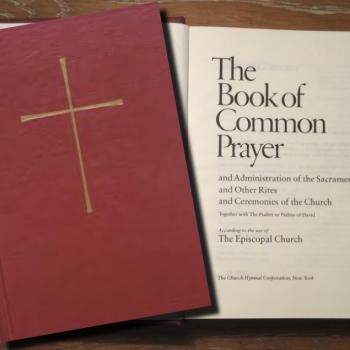

What has mattered is our media presence, live stream worship, personal outreach, and the effort we make to welcome people and include them in the life of the parish. This doesn’t mean that clarity about our identity isn’t important. I think that people are also powerfully attracted to the way in which we describe the place we occupy in the larger church: Ancient mysteries, modern faith. Sound exegesis, spiritual direction, engagement with the living Christ through the practice of the sacraments are central to our worship. We take time to explain what we do in our liturgy, why we do it, and its importance as a vehicle for an experience of the living God. And we refuse to let those priorities become a thin disguise for partisan politics.

I am convinced that has to be done, parish by parish. And neither the church nor the seminaries will find their way forward without getting down in the proverbial trenches to get a first hand picture of what clergy are facing. It will not come from conversations among seminary deans and it will not happen at General Convention. Denominational life so closely mirrors our national / political life that it is too deeply conflicted and removed from the life of the local parish to be the place where changes can be implemented.

I have served as a canon of two cathedrals – including the National Cathedral. I have been a member of the church’s General Board of Examining Chaplains, and I served as Dean of St. George’s College in Jerusalem, as a missionary of the Episcopal Church. But after almost 50 years of ordained life in two mainline denominations, I can honestly say that the only time decisions made at the national level affected life in the congregations that I have served when they made leadership on the local level more difficult.

I still believe in bishops as a symbol of the church’s unity and as a symbol of our obligation to the apostolic tradition. But I am functionally a congregationalist – both of necessity and by experience. And I do not believe that I am alone in that regard.

Years ago, one of my professors was invited to address a large gathering of bishops. After his address, he was asked what was the one thing that bishops should do. He grabbed a dinner napkin, folded into triangle and held it up for everyone to see. “This is the way the church functions,” he said. Then he turned the triangle up side down and remarked, “This is what it should look like.”

Mainline seminaries and denominations look to the local church for financial support, year after year, often at the expense of their own ministries. Now, more than ever, seminaries and denominational leaders should look to local congregations for clues to the shape of their own calling.