We need to talk about how woefully unable and unwilling are humans in general and Christians in particular to suffer well and grieve deeply.

We are, by evolution and/or design, creatures desperate for hope. To linger in grief or sadness, to admit that some wounds cannot be mended and some trauma never overcome, is, for many, to admit defeat. We do not know how to grieve with the grieving or groan as the Spirit does: “with groans too deep for words.” So when tragedy strikes or trauma greets us — whether it’s our own and especially when it’s another’s — we flee the pain and grasp for meaning, hope.

I get it: The alternative — that some trauma wounds kill a part of us, just as some physical wounds claim limbs — is deeply unsettling and uncomfortable. And we hate discomfort.

Sometimes, the Christian’s response is well-meaning but ineffective, though not necessarily damaging. After my near-death and hysterectomy, I heard every rote platitude in the book:

“Everything happens for a reason!”

“This is God’s sovereign will for your life. God is good, all he does is good, and therefore this is good. You must not be angry — anger is doubt, and doubt is rebellion.”

“You did this to yourself by allowing doctors to dictate your delivery. Had you trusted God and his way this wouldn’t have happened.”

And the go-to of all people who don’t know what to say about infertility: “Miracles happen!”

(These are all patently stupid responses.)

But other times, the Church’s unwillingness to acknowledge, grieve, and sit with the sting of lifelong trauma is deeply damaging, re-traumatizing, and abusive.

This is especially true when the trauma is directly inflicted by the church or its members. It is especially especially true when the abuser is a leader with power or platform to protect.

We all know this problem of covering up sexual crimes, defending predators, demonizing and silencing victims, and pivoting to a hope-her narrative that centers the accused is pervasive across denominations the church. (Twitter’s #ChurchToo, #YouDontKnowEvangelicals, and #EmptyThePews trends offers a free education on such things for anyone unaware.) And it is no clearer than in last weekend’s exposure of Memphis mega-church pastor Andy Savage’s history of sexual assault. In keeping with the church scandal modus operandi, Savage — who decried the crimes of sex predators in Hollywood during the apex of the #MeToo movement — used his Highland Church platform not to talk about the crime of using his spiritually authoritative position as a 20-year-old youth pastor to sexually assault and silence 17-year-old Jules Woodson, or their lead pastor’s failure to immediately remove him from his position and report his crimes to proper authorities.

He did not commit the moment to discussing spiritual and sexual abuse in the church, the lifelong impact it has on survivors, and how they as a church can support survivors and root out predation from within, starting with his resignation. Instead, they pivoted the narrative to defend Savage and focus on his redemption. Savage self-deprecatingly “confessed” his sin while detaching himself from his crime, repeatedly placing it in the distant past, and heroized himself for handling “the incident” (not rape or sexual assault) according to “biblical standards.” (And of course, they took a moment to underscore Woodson’s sin of unforgiveness.) All to the wild applause and standing ovation of congregants.

(I’ll pause here if you need to go vomit.)

Invariably and inevitably, this M.O. re-traumatizes survivors and reaffirms bad theology about patriarchy, women, modesty, sexuality, and predation.

The bottom line is that this story should never have been about another church predator’s supposed redemption, but about Jules’ bravery in coming forward with the truth about an abuser enjoying the unconscionable power of the mega-church pulpit.

But — and this is where we come full circle back to the problem humans in general and the church in particular has with suffering — the American church simply cannot abide that story.

After all, the entire western Christian narrative isn’t truly centered on Jesus whose subversion of religious and state authorities and alignment with the oppressed and marginalized ultimately got him killed, but on what that crucifixion and resurrection mean for individual Christians. This gospel isn’t about God incarnate demonstrating the Creator’s brilliant, beautiful, supremely relational empathy toward beloved creation — except as a bridge for worthless humans to be relieved of their total depravity. In a strange irony, a gospel which professes to be all about God’s grace (because man is mere scum) is, fundamentally, all about man getting away with rape and murder because of grace:

Their gospel is about Abraham and Sarah believing God’s promise and bearing the son who would bring God to all nations — Never about Hagar who was raped, impregnated, abused, and driven out for doing Sarah’s bidding; Hagar who spoke to God and named God “The God who sees me” and trusted God’s vindication.

It’s about David, the adulterous, murderous king who was yet a “man after God’s own heart” — Never about Bathsheba, who could not reject the king’s invitation and thus suffered rape, impregnation and child loss, and the murder of her husband by her rapist.

It’s about Saul of Tarsus, the persecutor and murderer of Christians who was blinded and believed — never about the martyrs he killed and only tangentially about the Christ who blinded him.

This western, hyper-individualistic gospel seems always to be centered on the truly deplorable man who turns into a hero (thanks be to God).

(I have theories as to why the western gospel is so thoroughly centered on the half-assed redemption of terrible humans, the preeminent being that the western church — especially the evangelical branch — has repeatedly been guilty of the worst crimes [like indigenous genocide, Trans-Atlantic slavery, purity culture, and the abandonment of LGBTQIA+ youth to homelessness and suicide], has always used the Bible to defend those crimes until the very last moment when they are finally forced by public outrage to change course, and then almost never actually confesses or repents of those deadly crimes, but simply sweeps them away as dark history or someone else’s sin. But I’ll save that for another post.)

But Jesus! A gospel centered on Jesus finds Christ on the margins with the oppressed and suffering, dining with the victims of bad theology (and occasionally correcting the bad theologians who eventually killed him for the crime).

In Jesus on the Cross and On the Way to the Cross we encounter the Man of Sorrow who understands the trauma of disease and death, injustice and abandonment. He is the Suffering Servant knows what it is to sweat blood in depression and anxiety and to cry for the nearness of friends to help carry his grief only to find them sleeping through his agony or later denying they ever knew him at all.

Jesus’ Gospel never trivializes, undermines, or pivots from trauma, but sits in it and lets it hurt.

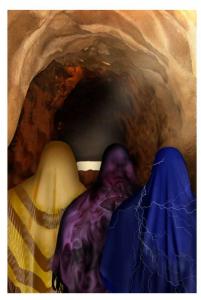

His is the Gospel of grieving the grave before accepting the hope of resurrection.

Early in our friendship, my dear friend and survivor Jessy told me the truth I’ve heard echoed a thousand times since from survivors of spiritual and sexual trauma within the church: Some wounds never heal.

And while our impulse as humans and christians is to fix, heal, medicate, numb, or silence pain, what all wounded survivors need isn’t to be fixed — they are not broken problems.

They need presence.

They need listeners.

They need acknowledgement.

They need people willing to come around them, face their wounds, groan for their trauma, and sit with the sting that never goes away.

And where we have been complicit in the wounding — whether directly as abusers, or indirectly as protectors or defenders of abusers — it is all the more crucial that we not defend, distance, detach, or pivot from the trauma we’ve inflicted, but to instead sit with the sting of our own sin, and the sting of the wounded, and grieve.