One of the central metaphors in the buddhadharma likens our usual world to a dream from which practice can help us awaken.

One of the central metaphors in the buddhadharma likens our usual world to a dream from which practice can help us awaken.

But what about the nonmetaphorical dream world we live through while asleep? What practice can we do there? Can the world of dreams also be a field for awakening?

In preparing for our upcoming practice period, “Expressing a Dream in a Dream,” I’ve been reflecting and reading about dreams. Are dreams important to you? How many dreams from this life do you remember?

I remember only about a dozen dreams from the thousands that I’ve dreamed.

For example, in about 1987, Katagiri Roshi told me to study the Abhidharmakosa, a commentary on the so-called “higher teachings” (a systematization of the original Buddha’s teaching with a technocratic psychological bent). I’m not sure why he wanted me to do that and don’t remember if I asked him or not.

Anyway, I waded through the first chapter repeatedly but found it impenetrable. Try as I might, I couldn’t find an entry point in “classif[ying] existing things into stained and unstained phenomena” or in the second chapters’ “describ[ing] how existing things are perceived.”

I don’t remember being bored, more like reading something that was supposedly in English but having no fricking clue as to the meaning of even a single sentence.

This was a new experience for me. I’d thought of myself as smart enough to at least have an inkling about what was going on in what I was reading but this was like walking into a brick wall.

So late one night, I put the text down in frustration, thinking I’d have to go to Roshi and tell him that I was just too stupid for it.

That night, I dreamed I was in a brightly lit room, at a party with a bunch of Zen students engaged in merry conversation, creating a cacophony of party voices. Suddenly, I saw in my right peripheral vision a woman of light, floating above the revelers. As I shifted focus to her, she said to me, telepathically I think, “Start with chapter three.”

Then she zipped up and away through the ceiling, I think.

I awoke in disappointment. “What a weird thing to say! ‘Start with chapter three’ – what the hell?”

Then it occurred to me that it might have something to do with the Abhidharmakosa. Doh! I opened to chapter three and found it absorbing, describing the various realms of existence, including the deva realm.

Later when I told Katagiri Roshi about my dream, he said, “Deva came to help you.”

“You believe in devas?” I asked him.

“Yes,” he said, “but don’t tell. It would encourage the people to be spiritual fascination.”

And that’s one of the reasons – concern about spiritual fascination that distracts us from the main point – that has led the modern Zen tradition to down-played dreams and their relevance in the spiritual journey, generally regarding them, like devas, as a form of makyo, or delusion (literally, “devil place”), making little or no distinction between dreams while sleeping, zazen lulling out, and other types of mystical visions.

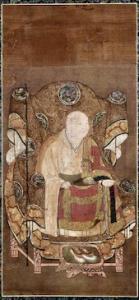

Back in the medieval period, though, dreams seem to have played a more significant role. See Bernard Faure’s Visions of Power: Imagining Medieval Japanese Buddhism (mostly a biography of Keizan, the 4th ancestor of Soto Zen in Japan), especially Chapter 5: “Dreaming.” Keizan, the author of the Record of Transmitting the Light or Denkoroku, was an “inveterate dreamer,” recording many of his dreams, and even basing important decisions (e.g., where to site a monastery) on dreams.

How we regard and interpret our dreams may tell us as much about ourselves as the interpretation itself. Just as in the modern world with our many ways of interpreting dreams (psychodynamically, archetypically, cognitively, random synaptic firing, etc.), there were also lots of views on the subject in the old days.

In medieval dharma circles, some divided the dream world into false dreams and true dreams. False dreams, I suppose, were like our normal anxiety dreams – finding oneself about to teach a class but not having prepared for it and whoops! what happened to my pants?

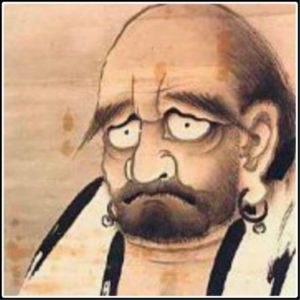

True dreams, occurring during the last watch of the night, included dreams as signs, supporting self-ordination, for example, which was apparently quite common – a political end-around of the powers that controlled ordination. Dreams as signs also gave credence to a teacher’s authenticity. Keizan was in good company when he dreamed that he received transmissions from Bodhidharma, Maitreya, and Shakyamuni.

In true dreams, the interpretation flips the usual Buddhist metaphor for dreams – dreaming is privileged and regarded as the world of true reality, hidden in the midst of our normal awake world which is a dim shadow of the rich dream world.

Of the various types of true dreams, Keizan was especially keen on premonitory dreams – with a Zen twist. When some land was donated to him, what became Yokoji, he dreamed that he saw the area filled with temple buildings and a bustling monastic community. In the center was a large hackberry tree with many pairs of monks’ sandals hanging from the branches, indicating that many pilgrams had come to train. Later, while awake and walking the property, Keizan found what he regarded as the tree from his dream. For Keizan, this tree represented a truth happening point, a realization of the koan, a place in the visible world that intersected with the hidden world of dreams. He viewed this as confirmation of the truth of his dream, and interpreted it as meaning that it was at Yokoji that his lineage would flourish.

“Sweet dreams are made of this,” sang the Eurythmics.

Ironically, Keizan’s lineage did flourish and it is through him that all surviving lines of Soto Zen flowed – but at Sojiji, not Yokoji. Yokoji quickly faded from historical significance.

As for me and the dream I recounted above, well, I did study the Abhidharmakosa for a while, but despite the dream visitation by what Katagiri Roshi regarded as a deva, I didn’t continue that pursuit. Maybe there’s a disappointed deva hanging out at a party of light somewhere or an alternate universe where I’m a Buddhist scholar.

Also the experience didn’t convert me to believing that I saw a deva. I remained a skeptic, regarding the experience as a glimpse at Katagiri Roshi’s hidden world view. I found it really interesting that he believed in devas (maybe the medieval view of dreams wasn’t dead after all) but that wasn’t grounds for my own deva conversion.

It did widen my world view, though, and opened me to a wider range of possibilities, many of which I just couldn’t explain or understand.