Dirty Little Secret?

According to the Urban Dictionary, that esteemed and profound arbiter of taste and discernment, a “dirty little secret” is “A secret that you don’t want anyone to know but someone finds out about it sooner or later.”

The secret in this case is a break in the Soto transmission between the forty-third and forth-fourth generations, between about 1020CE and 1050CE in China. Although I’m referring to it here as a dirty secret (tongue in cheek), many of those inside the Soto tradition know about this break. It is featured prominently in Keizan’s Denkoroku (Record of the Transmission of Illumination), Chapter Forty-Four, one of his longest chapters. Nevertheless, this issue is seldom talked about, perhaps because the implications undercut a key premise of the Soto tradition.

Afterall, the mind-to-mind transmission from the Buddha through Bodhidharma, Huineng, Dogen and all the successive generations of ancestors to the present day is the very heart of Soto Zen legitimacy. So, you might wonder, is the Soto Zen a legitimate Zen line?

That’s the question I’ll be exploring in this post.

It should not surprise us, though, that in this world where everything is broken, that there would be broken lineages too. (1) By the way, the Japanese Rinzai lineage also has its own set of such issues, including that of the transmission between the seventy-second (Dokyo Etan) and seventy-third generations (Hakuin Ekaku). Hakuin, you see, had only trained with Dokyo (aka Shoju) Roshi for about eight months and doesn’t seem to identify Dokyo as his transmission teacher until later in life.

And before Hakuin, in seventeenth century China, questioning a lineage’s legitimacy was something that both Soto and Rinzai teachers got into with wild abandon (and lack of social skills), like old people and pickle ball (except for the social skills part), and it led to some serious conflicts that weren’t resolved until the emperor stepped in. (2)

Click here to support my Zen teaching practice of which translations and writings like this are one facet – via Patreon.

The not-so sordid details

Nevertheless, this post is about one specific lineage gap that was closed remotely or through consignment. The story goes like this: in the forty-third generation of the Soto transmission, the sixteenth generation in China, the Soto lineage master Dayang Jingxuan (942–1027) was near the end of his life and hadn’t found someone that he believed would carry his lineage to the next generation. It is said that all of his successors had died before him. He was further concerned, we’re told, that the entire Soto line was about to die out. (3) Then he happened to meet a young monk and Rinzai lineage successor, Fushan Fayuan (991-1067), while the later was on post-transmission pilgrimage. (4)

Dayang and Fushan found that they were in harmonious accord. So Dayang offered Fushan his seal of transmission. Fushan declined, however, because he had already received transmission from Shexian Guisheng (no dates), as mentioned, in the Rinzai succession. (5) Instead, Fushan offered to hold Dayang’s Soto lineage in consignment. Should a suitable person come to Fushan, he offered to then remotely pass Dayuan’s Soto line to them. As the story goes, given that Dayang’s only other option was for the whole Soto lineage to die out, he took Fushan up on his offer.

Incidentally, for obvious good reasons, neither the contemporary Japanese Rinzai nor Soto schools would recognize this kind of transmission today.

There are, of course, some kinks in this story. First, the transmission records do not support the story element that Dayang had no successors that would outlive him. Dayang was a highly esteemed and well-known teacher who even received a posthumous name, Mingan Dashi (明安大師, Bright Peace Great Teacher), from the emperor. And the transmission records indicate that Dayang had at least seventeen successors, so it seems unlikely that they all would have died prior to Dayang meeting Fushan in about 1020. (6)

It is surprising, though, that just five generations after the great Dongshan Liangjie, the Soto line seems to have been gasping its last breaths – that part of the story seems true. An observer of the Zen scene shortly after this period, wrote in 1061, “Today, the followers of the families of the Yunmen, the Linji, and the Fayan are in great abundance. But the Guiyang has already become extinct, and the Caodong (Soto) barely exists, feeble like a lonely spring during a great drought.” (7)

But before we go on, one more twist in the story: Andy Ferguson notes that Fushan, the monk who turned down dharma transmission from Dayang because he’d already received transmission from Shexian, also received transmission from Fenyang Shanzhao, an ancestor of what became the mainline Rinzai transmission to Japan and through to us today. (8)

If like Fushan, you had already received a couple transmissions and an old dying Buddha asked you to receive their line too, you might say, “What the heck, what’s one more?”

But not Fushan.

The story continues

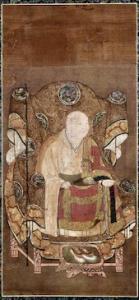

Nevertheless, whatever the circumstances, it seems well established that Fushan declined transmission from Dayang, but accepted the responsibility to transmit Dayang’s dharma should a suitable person appear. Dayang then gave Fushan his “lineage essentials” (宗旨; Dayang’s mortuary portrait, leather shoes, and kesa).

Now I wonder, given that Fushan accepted Dayan’s lineage essentials and took on the responsibility to transmit his lineage, is that really all that different from Fushan himself accepting transmission? I’d say “not so much” – he clearly offered to function as Dayang’s dharma heir.

Indeed, about twenty-five years later, Fushan found an appropriate person in Touzi Yiqing (1032-1083). (9) Touzi, notably, was born five years after his mind-to-mind transmission teacher, Dayang, had died. Fushan handed off Dayang’s lineage essentials to Touzi and the line has continued ever since.

After Touzi’s awakening, he seems to have stayed with Fushan for a few years and then went on pilgrimage. One well-known story has him visiting a teacher in the Yunmen line and sleeping all day. (10) However, the records do not indicate that he studied with any teachers in the Soto line, although there probably were still a few lingering around somewhere, like in a desert outpost or some such place. And I’d think that if I’d just been given a consignment transmission, I would want to check out some of the direct family members. Not Touzi.

Nor, by the way, had Touzi studied with any Soto teachers before his training with Fushan, as far as I can tell. So if there was something unique about the Soto line, Touzi would not have received it from any Soto teacher.

Nevertheless, he persisted admirablably and continued the Soto line.

Enter Keizan and the Japanese tradition

Keizan Jokin (1264-1325) in his above mentioned The Record of the Transmission of Illumination, explains this gap in the Soto lineages forty-fourth generation of face-to-face transmission at length, including saying, “Having reached this point, you should know that fundamentally there is no separation between Qingyuan and Nanyue.” (11)

Keizan’s comment here takes us back to the thirty-fourth generation, the seventh generation in China. Qingyuan refers to Qingyuan Xingsi (d. 740), the successor of the Sixth Ancestor through whom the Soto lineage traces its ancestry. Nanyue refers to Nanyue Huairang (677-744) the successor of the Sixth Ancestor through whom the Rinzai lineage traces its ancestry. (12) Just like my old teacher, Katagiri Roshi, Keizan encourages us to return to the Zen of the Sixth Ancestor, before any splitting occurred. Note: there already was splitting, but for the sake of simplicity, let’s just stick with the standard line on this one.

Anyway, Keizan justifies the consignment transmission between the Soto lineage’s forty-third and forty-fourth generations by asserting that Zen is One School. Keizan quotes Touzi justifying his transmission himself saying,

“Fushan kindly instructed me, saying, ‘Instead of me, you should carry on Dayang’s lineage style.’ Although this mountain monk never met Master Dayang, I came to know him through Fushan’s protection of the lineage, and due to that became [Dayang’s] successor in this way. Furthermore, I did not dare refuse the blessing of Fushan’s entrustment of dharma life to me. I reverently [hold up this incense] for Great Reverend Mingan of Mount Dayang in Yingzhou Prefecture. Why? Because neither my father and mother nor all the buddhas are my parents. I regard the dharma as my parent.” (13)

“I came to know him through Fushan’s protection of the lineage” is an interesting expression, but Touzi says no more about what he means by it.

In any case, Touzi and Keizan saw Touzi’s transmission pretty much the same way.

But how about Dogen? He was in the Soto succession just seven generations after Touzi. FYI, for context, I’m just six generations after Harada Sogaku Roshi (1871-1971). So it was fairly recent stuff for Dogen. How did he see it?

Shhhh! Somebody wanted to keep it quiet

Dogen, you see, included Touzi’s awakening story in his Eiheikoroku, volume 9.33. Here is my translation:

The Venerable Touzi Yiqing attended Dayang for three years. One day Dayang asked Touzi, “An outsider asked the Buddha, ‘Disregard having words, disregard having no words.’ The World Honored one paused. What about this?”

Touzi considered and was about to respond. Dayang covered his mouth. Touzi clearly uncovered awakening, then bowed. Dayang said, “Have you wonderfully awakened the profound function?”

Touzi said, “Let’s say I have – also I must spit it out.”

Then the attendant Zi, who had been sitting to one side, stood and said, “Today Touzi is sweating like he’s sick.”

Touzi said, “Shut your dog mouth.”

Dogen’s verse

Although his mouth was closed, how about his nose?

Let’s say he hasn’t swallowed, how’s it going to work to spit it out?

Acting remotely as the next generation of the lineage branch

Blue sky, lightning stops, stars vivid (12)

There is a lot that I’d like to say about this passage including about “Shut your dog mouth,” but I’ll keep it short. First, Touzi opened to profound functioning with the help of a koan that we still use today. There is also the play throughout with a closed mouth and spitting that is fun for our inner-twelve-year olds.

But the main reason for quoting this here is this quirky detail – Dogen’s text has Dayang as Touzi’s teacher even though Dayang died five years before Touzi was born. And Dogen knew it, as he discloses in the third line of the verse – “Acting remotely as the next generation of the lineage branch.”

What’s up with that?

Leighton and Okumura, in a note to their translation, speculate that an editor (or maybe copyist) at some point during the many hundreds of years of the Eiheikoroku’s life, switched out Fushan for Dayang. They note that in the Record of the Universal Lamp of the Jiatai Era (compiled before 1252), this same story of Touzi’s awakening is with Fushan, not Dayang. Keizan also presents it as such in his The Record of the Transmission of Illumination from the early fourteenth century. (14)

Short story – somebody wanted to hide the family secret. And apparently none of the many monks and scholars over the generations who must have known better, noticed or made the correction.

But curiously, Dogen in his “Face-to-Face Transmission” (Menju 面授) fascicle of the Shobogenzo goes on at length about the issue of dharma transmission, insisting that transmission must be face-to-face. He gives blow after blow to the monk Chenggu (a contemporary of Touzi) who claimed to have received transmission from the great Yunmen (864 – 949) – through reading Yunmen’s record! Yunmen would have died about seventy years before Chenggu made this claim. Dogen says to Chenggu (although Chenggu had been dead for long time – so many dead bodies),

“You have not yet seen Yunmen with your own eyes; you have not yet seen the self with your own eyes. You have not seen Yunmen with Yunmen’s eyes; you have not seen the self with Yunmen’s eyes. There are many people like you who have not thoroughly studied. Continually buy straw sandals and seek an authentic master from whom to receive dharma.” (15)

Although a distinction could be drawn between claiming a transmission through literature as Chenggu did and Touzi meeting face-to-face with Fushan (who had profound accord with Dayang), Dogen doesn’t mention Touzi at all in this fascicle. You’d think a person who lived in a glass house, might at least explain. Not Dogen.

Given all of this, is the Soto line legit?

In my view, not if the transmission between the forty-third and forty-fourth generation is something we’re trying to hide or if we insist on the letter rather than the spirit – in this case, that Fushan, as a Rinzai lineage master, could not give transmission to Touzi in Dayang’s Soto lineage because Rinzai and Soto are essentially different. Seems to me that it isn’t reasonable or intellectually honest to try to have it both ways.

One way around this (which I offer tongue in cheek) would be to consider Touzi’s transmission legitimate through Fushan and the Rinzai succession as a Rinzai transmission in either or both Shexian’s and Fenyang’s lineages, thus making contemporary Soto Zen a branch of the Rinzai Zen.

But, seriously, yes, the Soto line is legitimate – if we consider the Soto lineage secret (a twenty-five to thirty year gap in the mind-to-mind transmission) as a demonstration of One School Zen, embracing Keizan’s perspective – essentially, because there is no difference in what is realized and transmitted by Huineng’s successors, it makes no difference that Touzi received a consignment/remote transmission through Fushan, a legitimate successor in the lineage of the Sixth Ancestor.

An outflow of this overt recognition (that I embrace – I’m making it up after all) would be for us to include Fushan in the Soto lineage succession following Dayang so that Soto line is in fact an unbroken lineage (or a less broken lineage) from the Buddha. Fushan, after all, functioned as Dayang’s successor in everything but name. Granted, he declined Dayang’s transmission, but somebody’s got to get dirty in this situation. Might as well be Fushan.

An analogous case is that of Dokyo Etan and Hakuin Ekaku mentioned above. Given Hakuin’s Way power for guiding others on the path of awakening, no one doubted the legitimacy of Hakuin as an authentic Zen master. The truth of this has been verified by more than a dozen generations of Rinzai Zen masters.

Likewise, Touzi proved the legitimacy of his transmission through the fruits of his labors, producing seven successors, including the great masters Dahong Baoen and Furong Daokai who led a huge revival of the Soto school (16). And the Soto school is still more or less alive and kicking almost one thousand years later.

That oughta be enough proof.

In the last post, Soto and Rinzai Zen: One School or Two? I said that in this post that I would explain why in the thirteenth century the two lines were so much the same. The reason is embedded in the above – they actually had been one and the same just six generations previously when Fushan trained the teacher that continued the Soto lineage for all future Soto generations – the Rinzai monk, Touzi Yiqing.

(1) Thanks to Tetsugan Sensei for reminding me of one of McRae’s Rules of Zen Study: Lineage assertions are as wrong as they are strong. Statements of lineage identity and “history” were polemical tools of self-assertion, not critical evaluations of chronological fact according to some modern concept of historical accuracy. To the extent that any lineage assertion is significant, it is also a misrepresentation; lineage assertions that can be shown to be historically accurate are also inevitably inconsequential as statements of religious identity.

Also note that in this essay, I’ll use the Japanese “Soto” and “Rinzai” for whole lineages, including the Chinese Caodong and Linji – to aid the reader. However, that isn’t to say that I assume that Caodong = Soto or that Linji = Rinzai. One led to the other, but I’m afraid we have a “same or different” issue here that is beyond the scope of this post.

(2) For a fascinating read through this, see Jiang Wu’s Enlightenment in Dispute: The Reinvention of Chan Buddhism in Seventeenth-Century China.

(3) Dayang Jingxuan is 大陽警玄; 942–1027; Japanese, Taiyo Kyogen; English, Great Yang Mysterious Warning.

(4) Fushan Fayuan is 浮山法遠; 991-1067; Japanese, Fusan Hoen.

(5) Shexian Guisheng is 首山省念, no dates.

(6) See Morten Schlutter’s How Zen Became Zen The Dispute over Enlightenment and the Formation of Chan Buddhism in Song-Dynasty China, 90.

(7) Ibid. 79

(8) Fenyang Shanzhao is 汾陽善昭; 942-1024; Japanese, Fun’yo Zensho.

(9) Touzi Yiqing is 投子義青; 1032-1083; Japanese, Tosu Gisei; English, Abandoned Child Blue Devotion.

(10) The Yunmen lineage successor was Yuantong Shen in the forty-fourth generation. The source for this is Andy Ferguson’s Zen’s Chinese Heritage:

Zen master Fayuan sent Touzi to study with Zen master Yuantong Shen. But when Touzi arrived at Yuantong’s place, rather than going for an interview with that teacher at the appointed time, he remained sleeping in the monk’s hall. The head monk reported this to Yuantong, saying, “There is a monk who’s sleeping in the hall during the day. I’ll go deal with it according to the rules.”

Yuantong asked, “Who is it?”

The head monk said, “The monk [Touzi].”

Yuantong said, “Leave it be. I’ll go find out about it.”

Yuantong then took his staff and went into the monk’s hall. There he found Touzi in a deep sleep. Hitting the sleeping platform with his staff, he scolded him, “I don’t offer any ‘leisure rice’ here for monks so that they can go to sleep.”

Touzi woke up and asked, “How would the master prefer that I practice?”

Yuantong said, “Why don’t you try practicing Zen?”

Touzi said, “Fancy food doesn’t interest someone who’s sated.”

Yuantong said, “But I don’t think you’ve gotten there yet.”

Touzi said, “What point would there be in waiting until you believed it?”

Yuantong said, “Who have you been studying with?”

Touzi said, “Fushan.”

Yuantong said, “No wonder you’re so obstinate!”

They then held each other’s hands, laughed, and went to talk in Yuantong’s room.

From this incident Touzi’s reputation spread widely.

(11) Keizan Jokin is 瑩山紹瑾; 1264–1325; English, Lustrous Mountain Bequeathing Jewels. See The Record of the Transmission of Illumination, 440, and the whole of the chapter on the forty-fourth generation.

(12) Qingyuan Xingsi is 青原行思; d. 740; Japanese, Seigen Gyoshi; English, Green Source Walking Contemplation. Nanyue Huairang is 南嶽懷讓, 677-744.

(13) Keizan Jokin, 439. The names are modified to be consistent with the usage in this post.

(14) In my translation of the passage, I’ve used the name “Touzi” throughout. The original text uses several different names and titles, so I’ve simplified it for the reader. The color change is also to make it easier for the reader to distinguish my writing from Dogen’s.

(15) Taigen Leighton and Shohaku Okumura, trans, Dogen’s Extensive Record: A Translation of the Eihei Koroku, 558.

(16) Dogen, Treasury of the True Dharma Eye: Zen Master Dogen’s Shobo Genzo, “Face-to-Face Transmission.”

(16) Dahong Baoen is 大洪報恩; 1058–1111; Japanese, Daigu Ho’on) and Furong Daokai is 芙蓉道楷; 1043–1118; Japanese, Fuyo Dokai; English, Lotus Flower Way Model.