Introduction

Meihō Sotetsu (1277-1350, 明峰素哲, Bright Peak Elemental Penetration) is the fifth generation Sōtō Zen ancestor in Japan, following Dōgen, Ejō, Gikai, and Keizan. If you are practicing Sōtō Zen with teachers in any of these lineages – Katagiri, Swaki, Harada-Yasutani, Aoyama, Bokusan-Kishizawa – you are practicing in Meihō’s dharma stream. Keizan may have regarded Meihō as his primary successor because he transmitted Dōgen’s robe to him.

However, another prominent successor of Keizan, Gasan Jōseki (峨山韶碩 1275–1366), gets a lot more attention today. In fact, in all of the several major histories that I most frequently turn to, little mention is made of Meihō and none tell this awakening story. (1) This might be because Gasan’s branch (派, Japanese, “ha”) was more successful during the first several hundred years of Sōtō history.

The Meihō-ha, though, had a resurgence beginning in the 17th Century, with Gesshū Sōko (月舟宗胡, 1618–1696) and Manzan Dōhaku (卍山道白, 1635-1715). Now the two major branches of Sōtō, the Meihō-ha and Gasan-ha, are apparently pretty equal in numbers. In Western Zen, the two largest lineages, Maezumi’s White Plum Asangha and Suzuki’s San Francisco Zen Center lineage, are Gasan-ha. However, both Maezumi and Suzuki Rōshis had dharma teachers that were Meihō-ha (Yasutani Rōshi for Maezumi and Kishizawa Rōshi for Suzuki). (2)

Therefore, it seems to me that modern Sōtō could benefit from more information about Meihō. So as a late addition to my series, “Dōgen’s Great And …” (see footnote 3 below for the list and links), in this post you will find my translation of most of one of Meihō’s biographies (in bold) with my brief comments (in normal type), then an excerpt from Meihō’s zazen instructions.

Click here to support my Zen teaching practice (of which translations and writings like this are one facet) via Patreon.

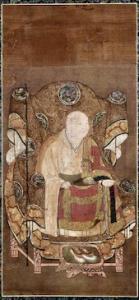

A Biography of Meihō Sotetsu Zenji (4)

The master’s name was Meihō Sotetsu. He was a person from Nō Province. His temperament was steady and he behaved without delusion. He wisely left home and studied the sutras of the teaching vehicle. He worried that the Zen essence was not offered at Kenninji. Finally, he came to Daijōji and paid his respects to Master Keizan.

It is notable that Meihō (referred to throughout with the last character of his second name, “Tetsu”), started practice at the Tendai-Zen lineage temple Kenninji that was founded by Eisai. In the previous century, Dōgen had trained in this temple as well, both before he went to China and again after his return. Daijōji was a temple that Gikai, Keizan’s teacher, had converted from a Shingon temple. It became a major practice center for Sōtō for many centuries, only recently losing it’s status as a training monastery (click here for more).

With one glance, Keizan ordered him to serve as his attendant (jisha). Inside the room, Keizan would often call, saying, “Jisha Tetsu.”

Tetsu would say, “Yes?”

Keizan would say, “What is it?”

Tetsu had no reply. He went on his worldly way for eight years. One day, Keizan said, “There is One Person who can transform the appearance of all things. Say now who this is!”

Tetsu again had no reply.

It is notable that Keizan appointed Tetsu to the important position of jisha after just a glance. And that Tetsu then served as Keizan’s jisha for eight years without ever being apart from him. Several other teacher-student relationships like this are recorded, for example, in the No Gate Barrier, Case 17: The National Teacher’s Three Calls, where the teacher calls his jisha three times. Wúmén’s notes that “He pushed down the ox’s head to eat grass, but the jisha was not yet ready to accept the burden.”

That was Tetsu’s condition for eight years while serving Keizan – every day his head being pushed into it – living with his teacher and steeping in the ancestral energy field. Imagine serving someone who’s steadily pushing and probing, “What is it?” “Who is it?”

Tetsu was one fortunate practitioner.

According to Bodiford, during this period, Keizan once found Tetsu reading a Zen text and scolded him, saying, “You have not yet answered my one question! How can you have any free time to imagine wanting to study that text?” (5) That surely speaks to the intensity with which Keizan expected Tetsu to train – if he were to breakthrough and offer a wholehearted response.

Many days later, he dropped thus, realizing satori. He went straight to the abbot’s room to directly express what he had realized. Seeing Keizan, Tetsu said, “Outer and inner layer are utterly dropped off – only this is the one true reality.”

Keizan said, “Dropping off dropping off.”

Important in this passage is both the fact of Tetsu’s satori and how he expressed it – a variation of Rújìng and Dōgen’s “bodymind dropped off.” “Outer and inner layer are utterly dropped off” harkens back through the generations of the Caodong/Sōtō lineage from Yaoshan in the thirty-sixth generation through Meihō in the fifty-fifth generation. Old wine in new bottles (see footnote 6 for more on the history of this phrase).

In addition, Keizan’s verification repeats Rújìng’s verification of Dōgen’s “bodymind dropped off” satori. One important takeaway here is how not only Rújìng and Dōgen, but also how the Japanese lineage played with the dual foci of continuity and creativity.

I’d be remiss if I also didn’t point out that it took Tetsu eight years of living with the great master Keizan to realize satori and discover that “…only this is the one true reality.” Some Sōtō folks these days would claim that there is no need to devote oneself wholeheartedly to the Way as it is already “…only this is the one true reality.” Without satori, though, such a belief is merely a head trip and by propagating such nonsense they defile the memory and the true intention of Keizan, Meihō, and all the buddhas and ancestors.

Tetsu then bowed to Keizan, displaying his perpetual light. [Keizan] invited [Tetsu] to share his seat and expound the dharma. He handed over the robe and explained in verse, saying,

“The lamp of perpetual light follows a person ablaze

Illuminate the broken kalpa with your new empty bearing

Protruding like a bright peak, difficult to conceal

All the merit of this transformed view reveals the whole body”

Although the exact amount of time that passed between Tetsu’s satori and his receiving dharma transmission is unclear, it appears to have happened shortly afterward, without the usual period of post-satori training. The robe mentioned above, as I said earlier, appears to have been the robe passed from Dōgen to Ejō to Gikai to Keizan and finally to Tetsu.

“Bright peak” in the third line of Keizan’s verse is 明峰, or Meihō, is Tetsu’s first name, so Keizan is playing with that here.

Tetsu received the robe, saying,

“Those who summit uphold nonarising words

Now having attained transformation, the gate is open

Then Keizan said, “When the causes and conditions exactly ripen, the time truly arrives.”

Meihō Sotetsu went on to serve as the abbot of Daijōji and Yōkōji. He left several successors, including Shugan Dōchin (珠巌道珍, d. 1387, Jeweled Crag Unusual Way) who also served as abbot of Daijōji.

An excerpt from Meihō’s zazen instructions

(1) These include Timeless Spring: A Soto Zen Anthology, trans Thomas Cleary; Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan, by William M. Bodiford; Zen Buddhism: A History: Japan, Heinrich Dumoulin; Zen Masters of Japan: Second Step East, by Richard Bryan McDaniel.

(2) Thanks to Bukkokuji monk Kōgen for sharing his thoughts on Meihō and Gasan lineages.

(3) This is the list of the posts from the “Dōgen’s Great And…” series. I’ll list them here in order of their places in the lineage:

- Punning, Toileting, Purifying: the Awakening of Rújìng: There are several awakening stories for Rújìng in the literature. One involves a pun about toileting and purifying. Available now publicly.

- Rujing and Six Intimate Dharma Heirs: In this post, Kōkyō Henkel offers an insightful preface and then his and Yashu Zhang’s enormously important translation of the section of the Record of Rújìng that is attributed to Dōgen, graciously offered here for Wild Fox Zen readers.

- Another Big Ugly Myth: Zen Lacks A Compassion Practice: This highlights the Great Compassion teaching of Rújìng, but also offers some basic Mahayana teaching that distinguishes compassion and Great Compassion

- How to Break Through Mu: The theme here is the Cáodòng/Sōtō master Rújìng’s instructions for breakthrough with the mu kōan – and my interpretation of such.

- Meeting People and Manifesting (or not): Two Slippery, Seamless Kōans for Advancing Practice This post is about practicing after kenshō. Following Rújìng (Dōgen’s teacher), I share two of the most fascinating, complexly interrelated kōans in the whole huge traditional collection of fascinating kōans, ideal for the phase of training known as “advancing practice.”

- Praise for the Old Buddha Rújìng & Dying Poem: This one is a summary of sorts and a new translation of Rújìng’s death poem.

- An Ancient Soto Master’s Praise for the Record of Linji: Linquan’s surprisingly positive blurb for the Rinzai Roku.

- The Luminous Koun Ejō Zenji: Background, Awakening, Legacy: In this post I share my enthusiasm for the teaching of Koun Ejō Zenji (Solitary Cloud Strong Heart, 1198-1280), the Japanese Sōtō Zen succession’s second generation ancestor. Old Ejō has been largely eclipsed by his master, Eihei Dōgen Zenji, and that’s just the way that Ejō wanted it to go.

- “Seven Stumbles, Eight Blunders: The Life of Tetsu Gikai.” Several levels of detail here including an accessible free-form bio, a translation from “The Biography of Sotō Masters in Japan,” and notes with explanations of terms and more historical background.

- Keizan’s “Answers to Ten Questions from the Emperor”: This post offers dharma gems from Keizan Jōkin Zenji (Lustrous Mountain Bequeathing Jewels, 1268–1325), the fourth generation in the Sōtō succession in Japan. Keizan is regarded as the second founder of Japanese Sōtō and is also known as Taiso Jōsai Daishi. The tenth Q&A is all about the mu kōan – not to be missed! This translation is by Kokyo Henkel.

(4) From Biographies of Japanese Soto Masters (日域洞上諸祖伝). Thanks to Ru Jing for sharing it.

(5) Record of the Transmission of Illumination, VII, “Introduction” by William M. Bodiford, p. 12. This essay is highly recommended for anyone interested in Sōtō history.

(6) Ibid., p. 40, “When asked by his teacher Mazu for his current understanding, the thirty-sixth ancestor, Yaoshan replies, ‘skin and dermis sloughed off entirely, there only exists a single true reality’ (this is Bodiford’s translation of what I’ve rendered “Outer and inner layer are utterly dropped off – only this is the one true reality”). Yaoshan may well have been the first person to utter this phrase, but he was not the last. Indeed, it occurs regularly in Chinese Chan texts, especially in those associated with the Dongshan lineage. In addition to Yaoshan it appears in the recorded sayings of ancestors 46, Danxia Zichun, and 47, Zhenxie Qingliao, as well as in those of Caodong figures Hongzhi and Zide Huihui. Hongzhi is a dharma heir of Furong (ancestor 45), and Zide is Hongzhi’s dharma heir. Clearly, Rujing and Dogen are drawing on a long tradition in their use of the variant, “body and mind sloughed off.”

(7) From ZEN: Poems, Prayers, Sermons, Anecdotes, Interviews, translated by Lucien Stryk & Takashi Ikemoto, p. 58. Modified.