Last night I took a break from course texts, Egyptology, and Pagan-metaphysical books to read a Patheos Book Club selection. Atchison Blue: A Search for Silence, a Spiritual Home, and a Living Faith is a tender personal account by PBS-TV religion reporter Judith Valente about the time she spends at Mount St. Scholastica in Atchison, Kansas.

Last night I took a break from course texts, Egyptology, and Pagan-metaphysical books to read a Patheos Book Club selection. Atchison Blue: A Search for Silence, a Spiritual Home, and a Living Faith is a tender personal account by PBS-TV religion reporter Judith Valente about the time she spends at Mount St. Scholastica in Atchison, Kansas.

I was curious to hear what would cause a reporter to take long breaks from her demanding work to go immerse herself in the world of the cloister. It may also be that subconsciously I was remembering fondly the consulting work I did for a few years in the Midwest with several monasteries, including Benedictine and Franciscan sisters.

As a Pagan, I found Valente’s story to be soothing and peaceful. She reflects regularly on the connection of the Atchison sisters to the seasons – both liturgical and natural – each of these a wheel of the year with which many readers will be familiar. Never having so much as visited a Catholic worship service when my consulting work began, my visits with the nuns were a whole new world for me. As I would tell my friends back home, these women really do take vows of poverty, celibacy and obedience, serving the people that no one else want to bother with. No wonder the Catholics love the sisters!

In fact, the entire narrative is suffused with a gentle but steady moving forward, a sort of waltz with the seasons of living that circles, steps back, then steps forward, rests, then circles again. Valente’s theme of seeking her own spiritual balance has found the perfect setting at Mount St. Scholastica, where the nuns vow to live there the rest of their lives, for better or worse. I heard so much of myself in Valente – anxiety about work performance, feelings of personal failure, driven to excellence yet insecure, anger and frustration with family. But among the sisters life is measured and predictable, even when events are unexpected (like a tornado), allowing introspection to do its work of spiritual maturing. “The mysticism of everyday life is the deepest mysticism of all,” as Valente says, quoting Sr. Macrina Widerkehr.

In fact, the entire narrative is suffused with a gentle but steady moving forward, a sort of waltz with the seasons of living that circles, steps back, then steps forward, rests, then circles again. Valente’s theme of seeking her own spiritual balance has found the perfect setting at Mount St. Scholastica, where the nuns vow to live there the rest of their lives, for better or worse. I heard so much of myself in Valente – anxiety about work performance, feelings of personal failure, driven to excellence yet insecure, anger and frustration with family. But among the sisters life is measured and predictable, even when events are unexpected (like a tornado), allowing introspection to do its work of spiritual maturing. “The mysticism of everyday life is the deepest mysticism of all,” as Valente says, quoting Sr. Macrina Widerkehr.

I have much to learn from the contemplative traditions. Valente reminds me of religious luminaries I have not read in many years, like Pierre Teilhard de Chardin: “‘We tend to think of the work of creation as something completed . . . but that would be quite wrong’ . . . The work of creation is always unfolding. We serve to complete it, he said, ‘with the work of our hands.’” This is also a core concept in our Osireion tradition; all the cosmos is inherently creative, our own nature is to create, and creation is a continuous, perpetual process. In this, we are like the gods.

There is something else here that gives me pause. Valente puts her finger on one of the reasons she has trouble maintaining her spiritual poise when she returns home (several hours away in Chicago). Back home she misses the community of the sisters. I think of how most Pagans now claim to be “solitary” and of how difficult it is in my own region to inspire any kind of collaboration or cooperation. The sisters don’t all like each other, and surely they don’t agree on everything, yet they have worked out the advantages of community, how to work together, how to support each other, even how to be apart together, and how to have regular times of silence. The Benedictines also value leisure as much as they do work, and include healthy portions of it in their daily living.

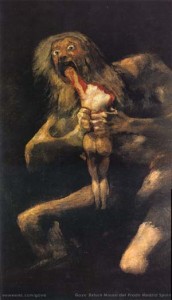

Finally, as I read this deliciously peaceful book, it occurs to me that one of the great gifts Christianity has given the world is that of self-reflection and humility. Humbleness is not a quality much prized in Pagandom, but for all that we would probably benefit from a little more of it. I fear too many of us have confused humility with shame, a useless and destructive emotion too often employed by so-called ministers of the Gospel. Like the sisters of my consulting days, the sisters at Atchison, however, are anything but timid. In fact, one of them is sister to noted anti-war activist Eileen Egan and is emphatically anti-violence, herself. Here she is, posing for a photo when Mother Teresa visited the monastery in 1981. A healthy humility strikes me as keeping my balance, staying grounded, maintaining a daily equanimity, being less likely to be knocked out of kilter.

If you have not made peace with your Christian upbringing, or if you have, and you just want to stroll through time to remember the good, the best, that Christian spirituality can offer, Atchison Blue takes you to the eye of the storm, a place of timeless wisdom.