My Aunt Grace was a businesswoman who took care of business. So when she died two years ago, no one in the family was surprised to learn that she had planned her interment down to the last detail. Every detail, that is, but what was to be said at her graveside. My aunt was Jewish. She had converted to Judaism when she married Eph. Most everyone else in her family – what was left of her family, that is (for she was 98 years old when she died) – most everyone in her family had remained Christian or had moved on to atheism, secular humanism or studied indifference. The upshot was, we the nieces and nephews of our childless aunt, were left with the question – how does a gathering of Christians and skeptics say a parting prayer for a Jew? As the religion writer in the family, I was appointed to figure it out. I had spent some time on the religion beat at a local newspaper, and my aunt’s executor concluded that I must therefore know a little something about

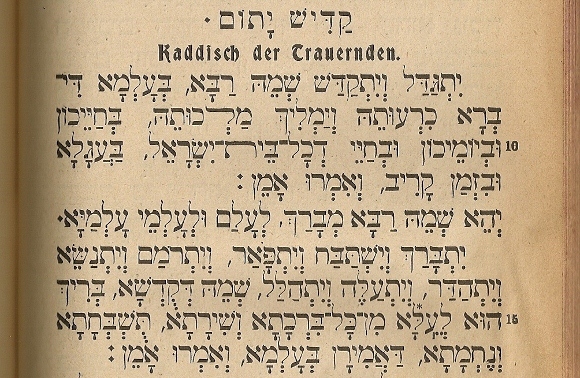

Judaism. Episcopalian though I was, it seemed my years as a religion writer qualified me to be the designated prayer at our Jewish aunt’s graveside. Grace had taken care of everything else: A mortuary was lined up in Arizona, where she lived, and one in Michigan, where she had been born and had chosen to be buried. Her casket was all picked out — white with gold trim. She had designated a svelte blue gown embroidered in gold as her burial gown. It had long sleeves and a high neck, the better to cover the inevitable signs of aging, illness and death. Awaiting her in Michigan was a gravesite in the little cemetery along Highway 10 between Ludington and Scottville. She would be buried there between her sisters and not far from her mother, father and grandmother. It was January when Grace died, so when we contacted the mortician in Scottville, he reminded us that it was still winter in Michigan. The ground was frozen. Our aunt couldn’t be buried until May, April at the earliest, after the ground had thawed. That gave me time to do some research. I knew that saying Kaddish was an important mourning ritual for Jews. You can say it for your mother or father, brother or sister, son or daughter, husband or wife. But who could say Kaddish for my aunt? Can an gentile say Kaddish? And what if the minyan — the traditional gathering of at least ten Jewish men required to say Kaddish — is neither Jewish, nor 100 percent male? My aunt had no sons or daughters to say it for her. Her parents and many siblings had preceded her in death. She was no longer connected to a congregation. She had outlived the rabbi who had overseen her conversion – as well as the husband who had inspired it in the first place.

If someone was going to say Kaddish for my Aunt Grace, it would have to be me. I went on line and googled Kaddish. I discovered that the Mourner’s Kaddish is not so much a prayer for the dead as a hymn in praise of a glorious God. Interesting, I thought. And fitting. A woman who’d had a full 98 years on the planet had died. A hymn in praise of the source of her life seemed about right. What didn’t go down so well with me was the excruciatingly medieval language of the Kaddish. God as male. God as king. God in (uppercase) His celestial heights. God’s great name. God’s will. God glorified, exalted, extolled and honored. Not my kind of God. And not the kind of God that would open the skeptical hearts and minds of certain of the nieces and nephews who would be gathering around my aunt’s gravesite. What to do? A little sleuthing and I learned that, sure enough, the prayer had its origins during a time of persecution after the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem. Small wonder that the rabbis who first prayed this prayer envisioned an almighty, ruler-of-the-universe God powerful enough to smite one’s enemies. I emailed my friend Andrea, who’s Jewish, for help. The next day, two translations of the Kaddish arrived in my in-box. One was a traditional, glorified-exalted-and-extolled translation. The other came from the Jewish Renewal movement. It was from the latter translation that with great trepidation – I wasn’t a Jew, after all, let alone a rabbi – I composed a translation (adaptation?) of the Kaddish. And so, on a rainy day in May, a dozen or so nieces and nephews and a couple of long-lost cousins-once-removed gathered in the rain at the Scottville cemetery and said a few last words in memory of our aunt.

In that company — a minyan maybe, maybe not — just before Aunt Grace’s white and gold casket was lowered into the sandy soil of Mason county, Michigan, a few miles from the farmhouse where she’d been born and a few miles from the Methodist church where she’d been reared, I recited this prayer for my aunt.

Mourner’s Prayer for Our Aunt Grace

Praise and thanks be to God throughout the world, which was created according to His intention.

May God’s light and love and justice be present in our lives, in the House of Israel, and in all of those who seek the truth. And let us say, Amen.

We praise, we continue to praise. And yet what we praise is beyond the grasp of the words and symbols that beckon us toward it. We know God, and yet we do not know. But still we pray.

We pray that God, who upholds the harmony of the cosmos, will create peace within us and between us, and within all who dwell on this earth. And let us say, Amen.

Mourner’s Kaddish from the Jewish Renewal Movement

May the great essence flower in our lives and expand throughout the world. May we learn to let it shine through so we can augment its glory.

We praise, we continue to praise, and yet, whatever it is we praise, is quite beyond the grasp of all these words and symbols that point us toward it. We know, and yet we do not know.

May the great peace pour forth from the heavens for us, for all Israel, for all who struggle toward truth. May that which makes harmony in the cosmos above, bring peace within us and between us, and to all who dwell on this earth, and let us say, Amen.

Mourner’s Kaddish, Traditional

Glorified and sanctified be God’s great name throughout the world which He has created according to His will. May He establish His kingdom in your lifetime and during your days, and within the life of the entire House of Israel, speedily and soon; and say, Amen.

May His great name be blessed forever and to all eternity.

Blessed and praised, glorified and exalted, extolled and honored, adored and lauded be the name of the Holy One, blessed be He, beyond all the blessings and hymns, praises and consolations that are ever spoken in the world; and say, Amen.

May there be abundant peace from heaven, and life, for us and for all Israel; and say, Amen.

He who creates peace in His celestial heights, may He create peace for us and for all Israel; and say, Amen.

Read more about my Aunt Grace at “How to Be a Glamorous Gal at Age 98.” If you’d like to read more about my Scottville family, check out “A Case of the Human Condition: Watching My Grown-Up Kids Disappear.” For a story about my father — Grace’s brother — go to “How Much Life Is Enough?” Learn about my new book at WrestlingWithGodBook.com.