One of the early agreements Webster Bull and I had when he invited me aboard the good ship YIMCatholic was that “we don’t do politics” here. And for the most part that is a wise way to go. There are, after all, a myriad of ways to elucidate why I am Catholic without making politics the lynchpin of the reason. Bill Watterson’s characters Calvin and Hobbes get it about right, don’t they?

Of course there is also the problem of writing about politics, which is that no one has a monopoly on the best, most efficacious political ideas, though everyone seems to think that they do. Ugly shouting matches rapidly ensue as a result. Combox grenadiers engage in rounds of last-word-to-the-death matches that rapidly lose any resemblance to civilized discourse. Another problem is that many folks confuse the rubbish of political party platforms with the fruits of actual political thought.

There also is the incontrovertible fact that the Church spans the entire political spectrum in regards to her thoughts and practices. As brighter lights than I have said, she is both liberal and conservative, but she is even more than that. To put it in terms like those would give you the false impression that she is like a bridge that merely spans a chasm between one side and another. She is not like that at all.

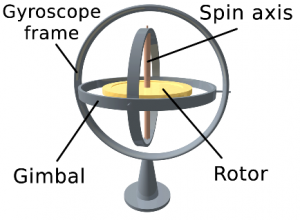

No, a better description would be that she is like a compass that always points to true North, no matter which direction you happen to be traveling at the time. After all, the full spectrum is three hundred sixty degrees, and not a single degree less. To be catholic is to be universal; therefore the thoughts encompassed by Catholicism are not, despite the cries of critics to the contrary, narrow but instead immensely broad. Which is why the compass of the Church is more akin to a gyroscope in three dimensions than a flat, circular, two dimensional one.

Too broad, actually, for any one person alone to grasp it all, though St. Thomas Aquinas has come the closest in this regard. Which brings us to the other problem of politics which is that it is undergirded by philosophical thought that many, if not most, have never learned. That fact in no way means that folks are too ignorant to engage in the political realm and in political discussions. And the reason for this is that one doesn’t have to be a credentialed philosopher in order to be an active participant in the affairs of the polity. This again stems from the Natural Law: our human ability to think and reason.

And so I’m back to sharing thoughts on the natural law, because as Catholics, the only mandate we have been given in terms of how we are to engage the political system that we happen to live under, is to do so with an informed conscience. And so that is what I am trying to do of late.

As a convert to Catholicism, I can tell you that I am in awe of all of the deep thinking that undergirds the Church’s stance regarding political thought. The philosophy is deep, mind blowing actually, and as refreshing for me to discover as it was to the folks who were in the original audience when Our Lord gave his Sermon on the Mount. That sermon is not conventional wisdom by any stretch of the imagination.

So here once again, after a very lengthy introduction by Joe Six-Pack, USMC, Bachelor of Arts, Political Science, UCLA, (yawn…big whoop) is John Courtney Murray, SJ with his concluding words from We Hold These Truths: Catholic Reflections on the American Proposition. I’ll preface them with a few words by someone you may have heard of.

”We must begin by a definition, although definition involves a mental effort and therefore repels.” —Hillaire Belloc on anything that requires thought.

Natural Law and Politics

In the order of what is called ius naturae (natural law in the narrower sense, as regulative of social relationships) there are only two self-evident principles: the maxim, “Suum cuique,” and the wider principle, “Justice is to be done and injustice avoided.” Reason particularizes them, with greater or less evidence, by determining what is “one’s own,” and what is “just” with the aide of the supreme norm of reference, the rational and social nature of man. The immediate particularizations are the precepts in the “Second Table” of the Decalogue. And the totality of such particularizations go to make up what is called the juridical order, the order of right and justice. This is the order (along with the orders of legal and distributive justice) whose guardianship and sanction is committed to the state. It is also the order that furnishes the moral basis for the positive legislation of the state, a critical norm of the justice of such legislation, and an ideal of justice for the legislator.

This carries us on to the function of natural law in political philosophy—its solution to the eternally crucial problem of the legitimacy of power, its value as a norm for, and its dictates in regard of, the structures and processes of society. The subject is much too immense. Let me say, first, that the initial claim of natural-law doctrine is to make political life part of the moral universe, instead of leaving it to wander, as it too long has, like St. Augustine’s sinner, in regione dissimilitudinis. There are doubtless a considerable number of people not of the Catholic Church who would incline to agree with Pius XII’s round statement in Summi Pontificatus that the “prime and most profound root of all evils with which the City is today beset” is a “heedlessness and forgetfulness of natural law.”

Thought break! Here is Summi Pontificus in it’s entirety. Go and read it when you get a chance. The natural law reference is in paragraph #28. Now we go back to the good professor,

Secretary of State Marshall (ed. that would be George C. Marshall, former Chief of Staff of the Army [1939-1945] and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize) said practically the same thing, but in contemporary idiom, when he remarked that all our political troubles go back to a neglect or violation of human rights.

For the rest, I shall simply state the major contents of the political ideal as it emerges from natural law.

One set of principles is that which the Carlyles and others have pointed out as having ruled (amid whatever violations) the political life of the Middle Ages. First, there is the supremacy of law, and the law as reason, not will. With this is connected the idea of the ethical nature and function of the state (regnum or imperium in medieval terminology), and the educative character of its laws as directive of man to “the virtuous life” and not simply protective of particular interests.

Secondly, there is the principle that the source of political authority is in the community. Political society as such is natural and necessary to man, but its form is the product of reason and free choice; no ruler has a right to govern that is inalienable and independent of human agency.

Thirdly, there is the principle that the authority of the ruler is limited; its scope is only political, and the whole of human life is not absorbed in the polis. The power of the ruler is limited, as it were, from above by the law of justice, from below by systems of private right, and from the sides by the public right of the Church.

Fourthly, there is the principle of the contractual nature of relations between ruler and ruled. The latter are not simply material organized for the rule of rex legibus solatus, but human agents who agree to be ruled constitutionally, in accordance with law.

A second set of principles is of later development, as ideas and in their institutional form, although their roots are in the natural-law theories of the Middle Ages.

The first principle is of subsidiarity. It asserts the organic character of the state—the right to existence and autonomous functioning of various sub-political groups, which unite in the organic unity of the state without losing their own identity or suffering infringement of their own ends or having their functions assumed by the state. These groups include the family, the local community, the professions, the occupational groups, the minority cultural or linguistic groups within the nation, etc. Here on the basis of natural law is the denial of the false French revolutionary antithesis, individual versus state as the principle of political organization. Here too is the denial of all forms of state totalitarian monism, as well as Liberalistic atomism that would remove all forms of social and economic life from any measure of political control (ed. this is Classical Liberalism, not New Deal American Liberalism). This principle is likewise the assertion of the fact that the freedom of the individual is secured at the interior of institutions intermediate between himself and the state (e.g. trade unions) or beyond the state (the Church).

The second principle is that of popular sharing in the formation of collective will, as expressed in legislation or in executive policy. It is a natural-law principle inasmuch as it asserts the dignity of the human person as an active co-participant in the political decision that concern him, and in the pursuit of the state, the common good. It is also related to all the natural-law principles cited in the first group above. For instance, the idea that law is reason is fortified in legislative assemblies that discuss the reasons for laws. So, too, the other principles are fortified, as is evident.

Conclusion

Here then in the briefest compass are some of the resources resident in natural law, that would make it the dynamic of a “new age of order.” It does not indeed furnish a detailed blueprint of the order; that is not its function. Nor does it pretend to settle the enormously complicated technical problems, especially in the economic order, that confront us today. It can claim only to be a “skeleton law,” to which flesh and blood must be added by that heart of the political process, the rational activity of man, aided by experience and by high professional competence.But today it is perhaps the skeleton that we mostly need, since it is precisely the structural foundations of the political, social, and economic orders that are being most anxiously questioned. In this situation the doctrine of natural law can claim to offer all that is good and valid in competing systems, at the same time that it avoids all that is weak and false in them.

Its concern for the rights of the individual human person is no less than that shown in the schools of individualist Liberalism (ed. think “Libertarianism”) with its “law of nature” theory of rights, at the same time that its sense of the organic character of community, as the flowering in ascending forms of sociality of the social nature of man, is far greater and more realistic. It can match Marxism in its concern for man as a worker and for the just organization of economic society, at the same time that it forbids the absorption of man in matter and its determinisms.

Finally, it does not bow to the new rationalism in regard of a sense of history and progress, the emerging potentialities of human nature, the value of experience in settling the forms of social life, the relative primacy in certain respects of the empirical fact over the preconceived theory; at the same time it does not succumb to the doctrinaire relativism, or to the narrowing of the object of human intelligence, that cripple at their root the high aspirations of evolutionary scientific humanism. In a word, the doctrine of natural law offers a more profound metaphysic, a more integral humanism, a fuller rationality, a more complete philosophy of man in his nature and history.

I might say, too, that it furnishes the basis for a firmer faith and a more tranquil, because more reasoned, hope in the future. If there is a law immanent in man—a dynamic, constructive force for rationality in human affairs, that works itself out, because it is a natural law, in spite of contravention by passion and evil and all the corruptions of power—one may with sober reason believe in, and hope for, a future of rational progress. And this belief and hope is strengthened when one considers that this dynamic order of reason in man, that clamors for expression with all the imperiousness of law, has its origin and sanction in an eternal order of reason whose fulfillment is the object of God’s majestic will.

And that, my dear reader, is one of the many reasons why I am Catholic. Do you see how dangerous these thoughts are to the status quo? And yet how close they match the thoughts of the Founding Fathers as they drafted the “Declaration of Independence” and the “Constitution of the United States?”

It’s also why I’ll be sharing more thoughts along these lines as time goes by. God, naturally, sees everything in the clear. We, on the other hand, as St. Paul (inspired by the Holy Spirit) writes “see through a glass, and darkly.” Thankfully we have the Church as the “bulwark of truth” from which we can bounce off the ideas of mere men to determine which of them are true and which of them are false. That, in a nutshell is what Fr. Murray’s book is about.

As Catholics and Christians, the very liberating, and paradoxical (to some) thing is that all subjects are open to study from the perspective of Christ’s teachings and that of the Church. That is to be expected, isn’t it? Seeking truth, finding truth, and measuring thoughts, ideas, concepts and systems by that very truth is in keeping with what we are called to do.

Note: Here, you can find the entire text of We Hold These Truths: Catholic Reflections on the American Proposition.